World oil trade

The impacts of the war in Ukraine

In a previous article we saw global oil supply and demand.

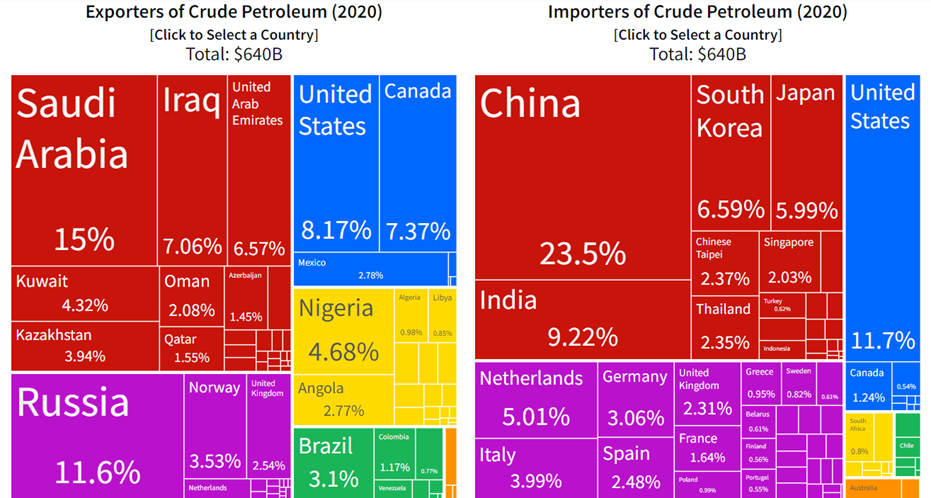

The following graph shows the main crude oil importing and exporting countries in 2020:

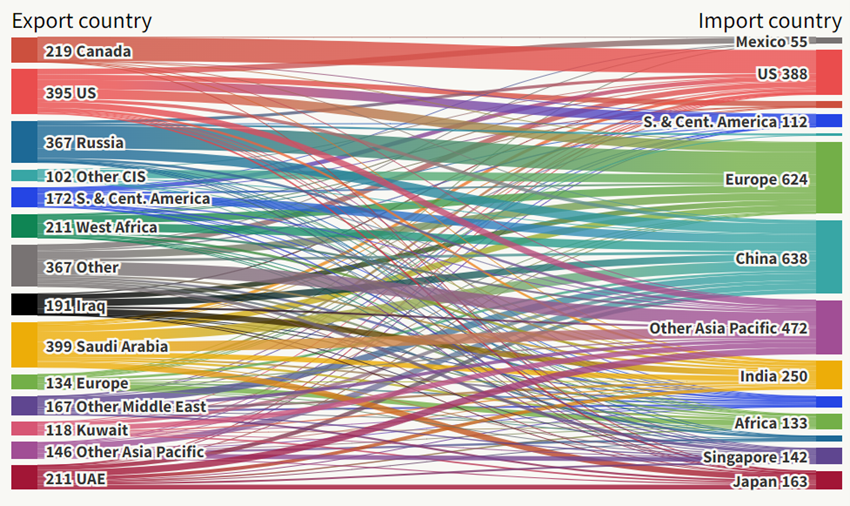

The following chart goes a little further and presents international oil trade:

China and Europe are the main net importing countries, with Russia as their main supplier.

Next come India and the Asian Pacific countries as importers, having as main suppliers the Middle East countries.

America is self-reliant.

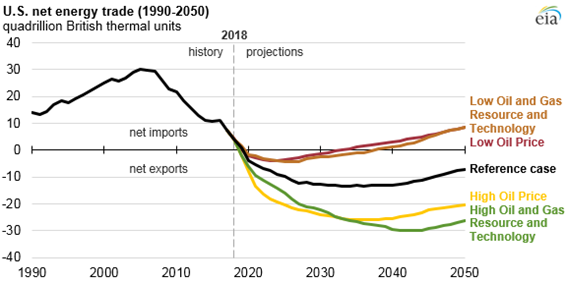

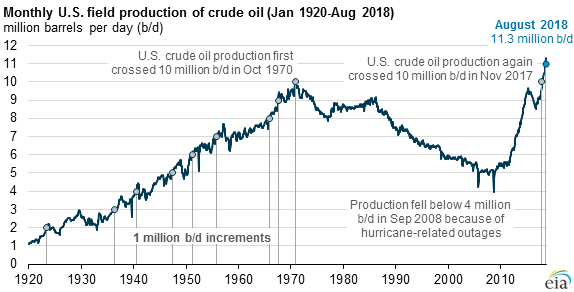

The US went from importers to net oil exporters in 2018:

This was the result of solving the problems of exploitation in the Gulf of Mexico, the focus on renewable energy, and especially the explosion of shale gas between 2010 and 2014.

The impacts of the war in Ukraine

There is a recent study by the Bruegel Institute very interesting and in-depth on this issue, which served as the basis for the development we will do next.

Russia exports about 5M b/d of which 2.8 M b/d to Europe and 2.1M b/d to Asia (of which 0.8M b/d to China).

These exports were 37% of total revenues in 2021 with the average price of $71/b.

The war in Ukraine brought Russia’s oil embargo to the West on the political and economic agenda.

Replacing the roughly 3M b/d of trade between the Euro zone and Russia is difficult but possible.

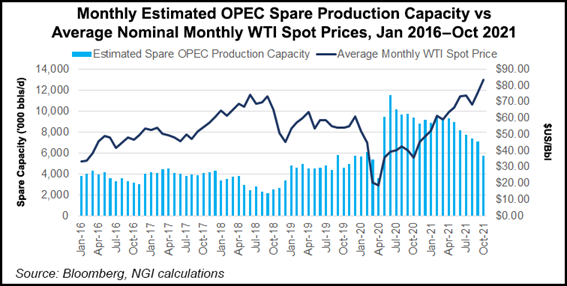

The following graph shows that the production capacity available in OPEC is about 5 million barrels per day:

OPEC countries have an available capacity of 4M b/d. This figure includes 1-2 mb/d from Saudi Arabia, about 0.75 mb/d from the United Arab Emirates and 0.5 mb/d from Iraq. Iran, currently locked in negotiations on the Iranian nuclear agreement, which will determine whether it can export oil, has about 1 mb/d of alternate capacity.

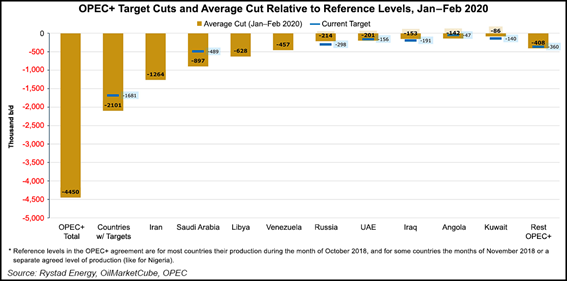

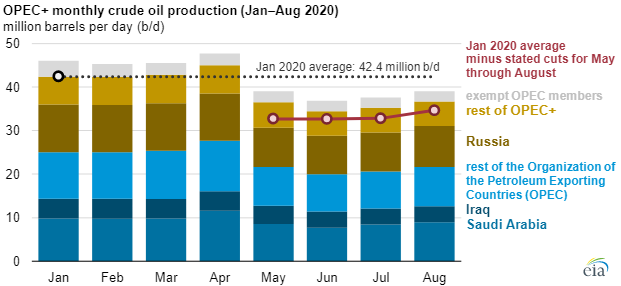

However, these countries are subject to opec+ agreed quotas with Russia not to increase monthly production by 0.4m b/d, agreed with the cuts of early 2020:

Moreover, these countries have already said that they will not change their position in the face of the war in Ukraine.

In addition, these countries have had difficulties in achieving the defined quotas:

With the European oil embargo on Russia and the new global geopolitical alignment, we will see a change in trade that will avoid further pressure on prices.

Unlike natural gas, oil is a well with greater ease of substitution from a technical point of view.

Most of the trade is done by sea transport while gas is transported mostly by pipelines.

Russian oil will be exported mainly to China and to a lesser extent to India, which will reduce its imports from other countries, mainly from the Middle East.

In this case, these countries will increase exports to Europe. For example, Italy has already established agreements with Qatar to this end.

In addition, non-OPEC+ producing countries such as Canada, the US and Norway may be an alternative especially if the price of oil remains so high that it makes the exploitation of sands and shale profitable.

The US has even admitted to freeing 180 million barrels from its strategic reserves to facilitate the European transition. Additionally, it is expected that shale gas production capacity will increase by about 1.5 million barrels per day, which takes about 6 to 12 months to extract after the start-up decision.

Finally, OECD members hold strategic oil reserves of 1.5 billion barrels. This offer could offset Russian exports at risk for about a year. Industry stocks are another 3 billion barrels.

Therefore, an immediate embargo on Russian oil can be partially mitigated by slowly withdrawing from strategic reserves, while boosting alternative production.

However, three major bottlenecks should be considered.

First, intra-European oil infrastructure was designed for movements in the west and not the other way around.

Second, some European refineries are optimized for Russian oil and will be less efficient with other types of oil.

Third, more complex than replacing crude oil is replacing refined products, which would lead European refineries to reach a capacity of 90% at the highest level of this century.

In addition, governments will be able to launch demand containment measures.

The European Commission considers that the Eurozone is able to reduce its dependence on Russian oil by at least 2/3 by the end of this year, most recently assuming its entirety.

The International Energy Agency (EIA) indicates a more moderate figure, for about half.

Russia’s oil independence from Europe is difficult, but possible.

Much more difficult and complicated is the case of the independence of natural gas, which is greater and alternatives are scarcer.

This issue of natural gas will be addressed in another article soon.

It does not seem believable to us that this oil shock, with its price doubling in less than a year, could cause a recession on its own, as some studies indicate and some experts argue.

However, the risks of recession in the current context do not come only from the price of oil.

There is the rise in prices of other goods such as natural gas, food and metals. There is also the rise in wages especially in the USA.

And the FED actions.

As early as the mid-last year, some economists were moving ahead with the threat of stout stemming from rising inflation without corrective measures by the FED.

Today these economists say that the risk is now of recession, adding to that factor, the worsening and the greater persistence of inflation brought by the increase in commodity prices associated with the war in Ukraine, still without more drastic measures to combat by the FED that they consider appropriate.

In another article we discuss this broader theme.