The types of overconfidence: Over ranking; Illusion of control; Optimism of the deadline; Effect of will

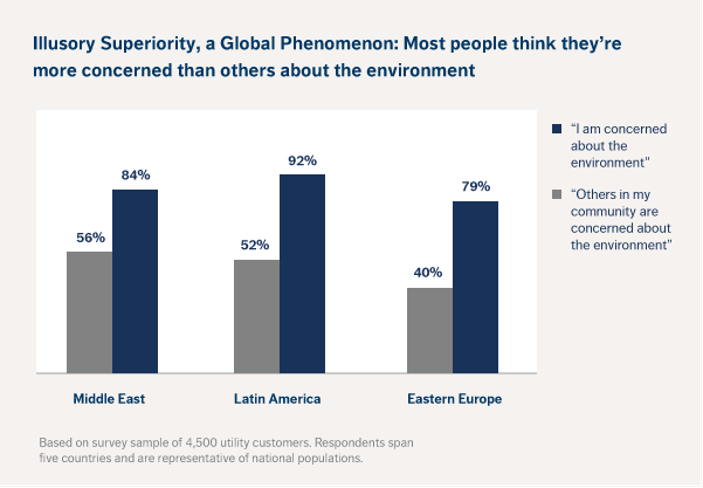

Ask anyone the opinion about himself and he will say he is better than average (not to risk saying he is better than all others)

Overconfidence or optimism is the belief that good things happen to us, and bad things happen to others.

The overconfidence effect is a well-established bias in which a person’s subjective confidence in his or her judgements is reliably greater than the objective accuracy of those judgements, especially when confidence is relatively high. Overconfidence is one example of a miscalibration of subjective probabilities.

Overconfidence comes in three different forms:

(1) Overestimation of one’s actual performance; tendency to overestimate one’s standing on a dimension of judgment or performance.

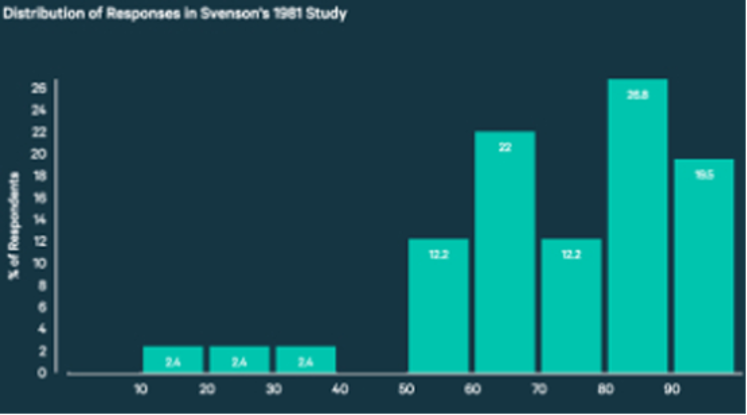

(2) Overplacement of one’s performance relative to others; Perhaps the most celebrated better-than-average finding is Svenson’s (1981) finding that 93% of American drivers rate themselves as better than the median.

(3) Overprecision in expressing unwarranted certainty in the accuracy of one’s beliefs. people believe themselves to be better than others, or “better-than-average. Overprecision is the excessive confidence that one knows the truth.

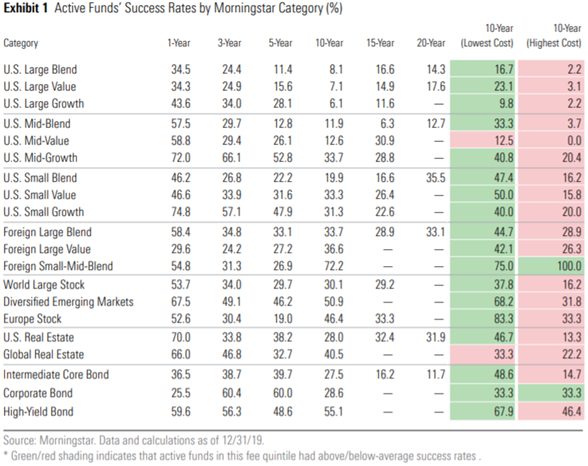

Many believe they beat the market… but the facts say that even most professionals are not able to do it

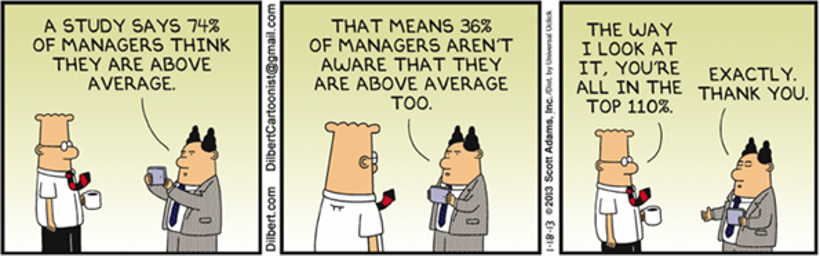

James Montier conducted a survey of 300 professional fund managers in 2006, asking if they believe themselves above average in their ability. Some 74% of fund managers responded in the affirmative. 74% believed that they were above average at investing. And of the remaining 26%, most thought they were average. In short, virtually no one thought they were below average. Again, these figures represent a statistical impossibility.

The reality is diverse, as can be seen in Morninsgtar’s latest study of about 5,000 investment fund managers in the US:

Over a 10-year period, only between 6.1% to 8.1% mutual fund managers beat the returns of large US companies stock market. This percentage rises to 19.9% for investments in US small companies, 33.7% for blend foreign stocks and 27.5% for treasury bond managers.

The overconfidence types

The easiest way to get a thorough grasp of overconfidence bias is to look at examples of how bias plays out in the real world. Below is a list of the most common types of biases.

#1 Over ranking

Over ranking is when someone rates their own personal performance as higher than it actually is. The reality is that most people think of themselves as better than average. In business and investing, this can cause major problems because it typically leads to taking on too much risk.

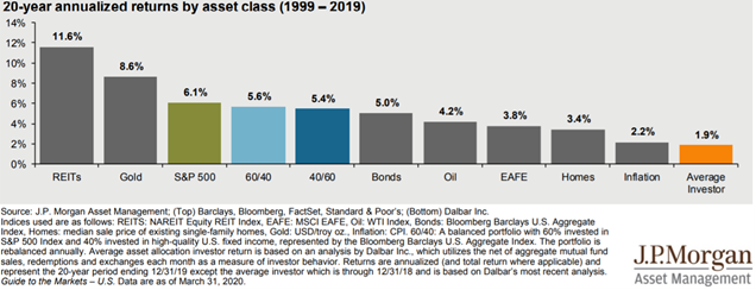

However, one of JP Morgan’s most recent publications contradicts this attitude, showing that the average investor has very low returns in their investments compared to the average returns of the various assets:

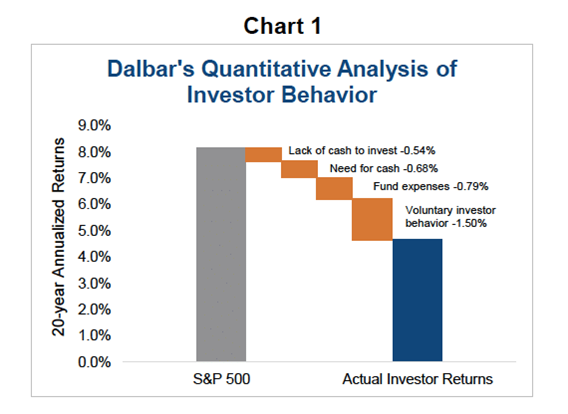

This situation is the result of poor allocation of assets, but also from behavioural biases:

This over ranking effect is known the ‘Lake Wobegon effect, coined by US psychology professor David Myers to refer to the tendency to irrationally overestimate one’s capabilities. The phrase pays homage to the fictional town created by author Garrison Keillor, where “all the women are strong, all the men are good looking, and all the children are above average”.

#2 Illusion of Control

The illusion of control bias occurs when people think they have control over a situation when in fact they do not. On average, people believe they have more control than they really do. This, again, can be very dangerous in business or investing, as it leads us to think situations are less risky than they are. Failure to accurately assess risk leads to failure to adequately manage risk.

This effect makes us prone to overestimating our part in successes and underestimating it in our failures, ignoring the role of chance. Worse, the illusion of control means we blame ourself when things do not turn out as planned. We start retrospectively analysing where we went wrong: “Did we invest enough?”; “Did we invest at the right time?”; “Did we invest in the right things?”

This is not only stressful, but by misjudging the cause of our mistakes we can be driven to further disappointments. We can correct a perceived weakness and still fail to achieve a better result.

The main effects of the investment under the illusion of control are as follows:

1. We can under-diversify, e.g. concentrating our investment into businesses or sectors we believe to have control over in some way, means we can under-diversify.

2. We can trade too often. Believing that our skill or past successes give us greater control over the outcome of our decisions may cause us to adopt bad trading habits. We might already run a profitable portfolio of investments, so this could encourage us to trade more often than necessary. The results are increased trading costs and exposure to unhealthy risk.

3. We can overestimate the value of information. Believing that a wealth of data allows us to predict what will happen in the future, is an overestimation at best. We might have read the annual report, analysed charts, reviewed historical patterns, and gone “all-in” without properly assessing the role of chance.

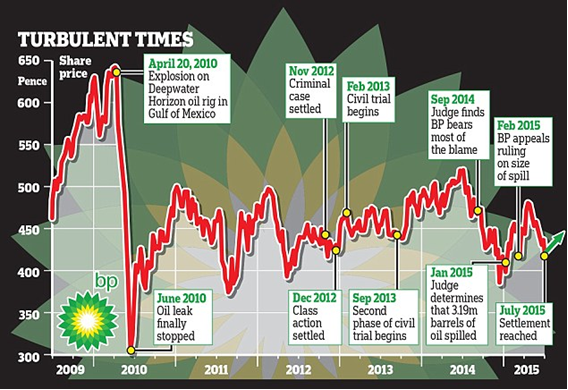

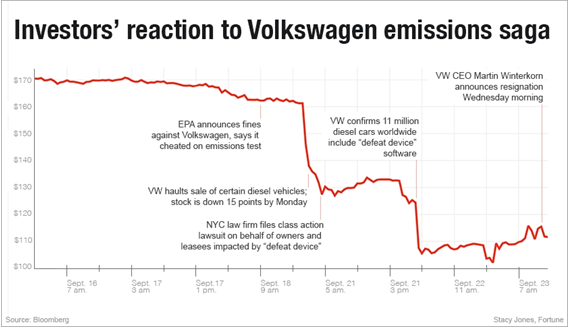

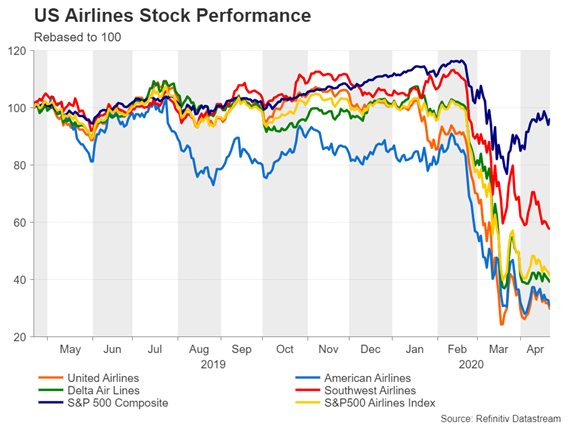

We are going to see some recent examples of random events that had a major impact on stock prices, including BP’s oil spill accident in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, the Volkswagen Dieselgate case and the effect of the Covid pandemic on the stock prices of major US airlines:

#3 Timing Optimism

Timing optimism is another aspect of overconfidence psychology. An example of this is where people overestimate how quickly they can do work and underestimate how long it takes them to get things done.

Especially for complicated tasks, businesspeople constantly underestimate how long a project will take to complete. Likewise, investors frequently underestimate how long it may take for an investment to pay off.

A good example of this situation occurred when the technological bubble or dotcom. In the late 1990s, an information technology bubble was created, culminating in a composition of almost 40% of the S&P 500’s market share entering 2000. The Nasdaq companies rose sharply, leading this index to trade at more than 100x the price multiple on results at the end of 1999.

#4 Desirability Effect

The desirability effect is when people overestimate the odds of something happening simply because the outcome is desirable. This is sometimes referred to as “wishful thinking” and is a type of overconfidence bias. We make the mistake of believing that an outcome is more probable just because that is the outcome we want.

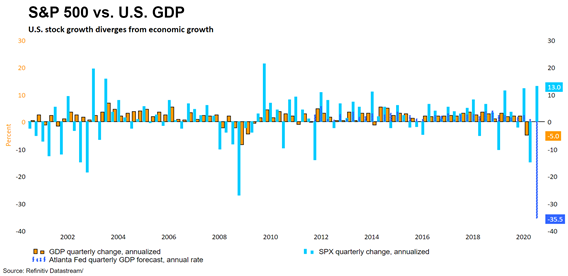

Today we are experiencing a time when there is a great disconnect between the situation of the economy and financial markets, as can be seen in the following graph:

One of the strongest explanations is that we want to believe that there will soon be a solution to the Covid pandemic in terms of vaccination and treatments.

Kahneman, a Nobel awarded economist once said, “Optimism is the engine of capitalism”. “Overconfidence is a curse. It is a curse and a blessing. The people who make great things, if you look back, they were overconfident and optimistic — overconfident optimists. They take big risks because they underestimate how big the risks are.”- But by studying only the success stories, people are learning the wrong lesson. “If you look at everyone,” he said, “there is lots of failure.”

John Maynard Keynes famously remarked it is “better to be roughly right than precisely wrong”. The lesson for investors is that it is necessary to be comfortable with uncertainty.

And as American sociologist William Bruce Cameron observed: “Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts”.

https://www.schwabassetmanagement.com/content/overconfidence-bias

https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/trading-investing/overconfidence-bias/

https://www.behavioraleconomics.com/resources/mini-encyclopedia-of-be/overconfidence-effect/

https://www.behavioraleconomics.com/resources/mini-encyclopedia-of-be/optimism-bias/