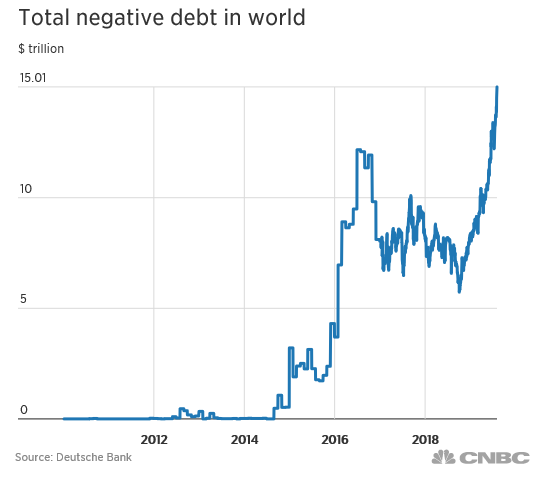

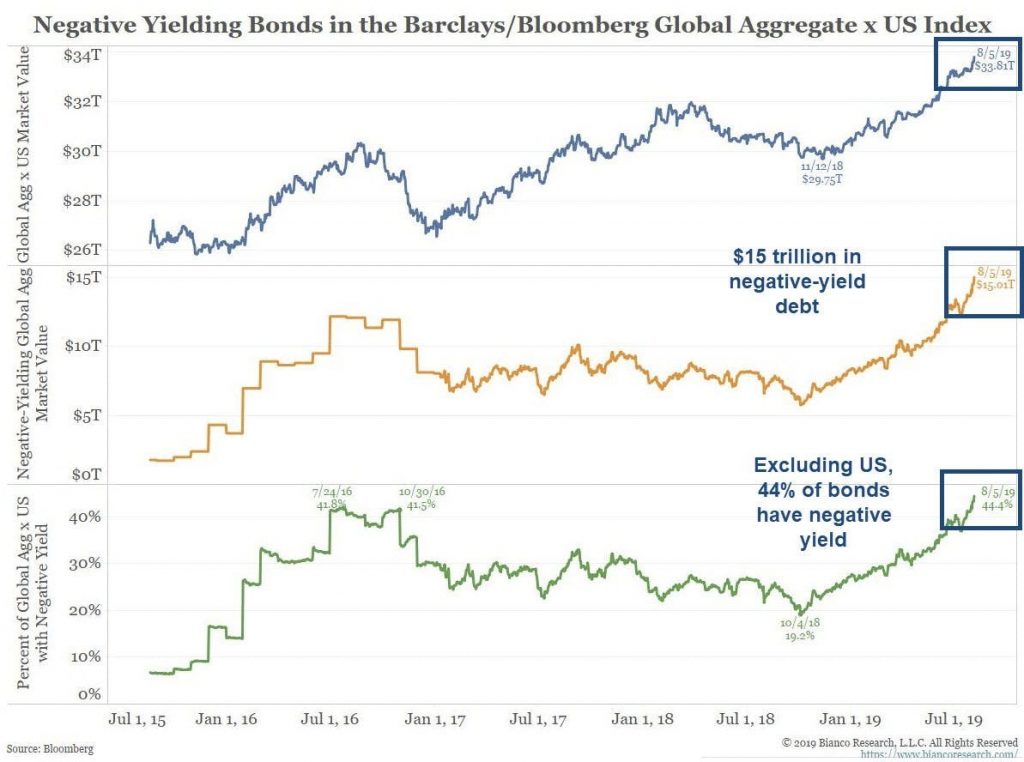

Currently, there are more than $15 trillion bonds, about ¼ of the global bond market, especially in Europe and Japan, with negative returns

Money has value and a cost (inflation plus more risk), so it doesn’t makes no sense to invest in negative interest rates

How did we come to so many trillions of bonds at negative rates?

Who wins and who loses?

So, if we lose as investors, what should we do?

Currently, there are more than $15 trillion bonds, about ¼ of the global bond market, especially in Europe and Japan, with negative returns

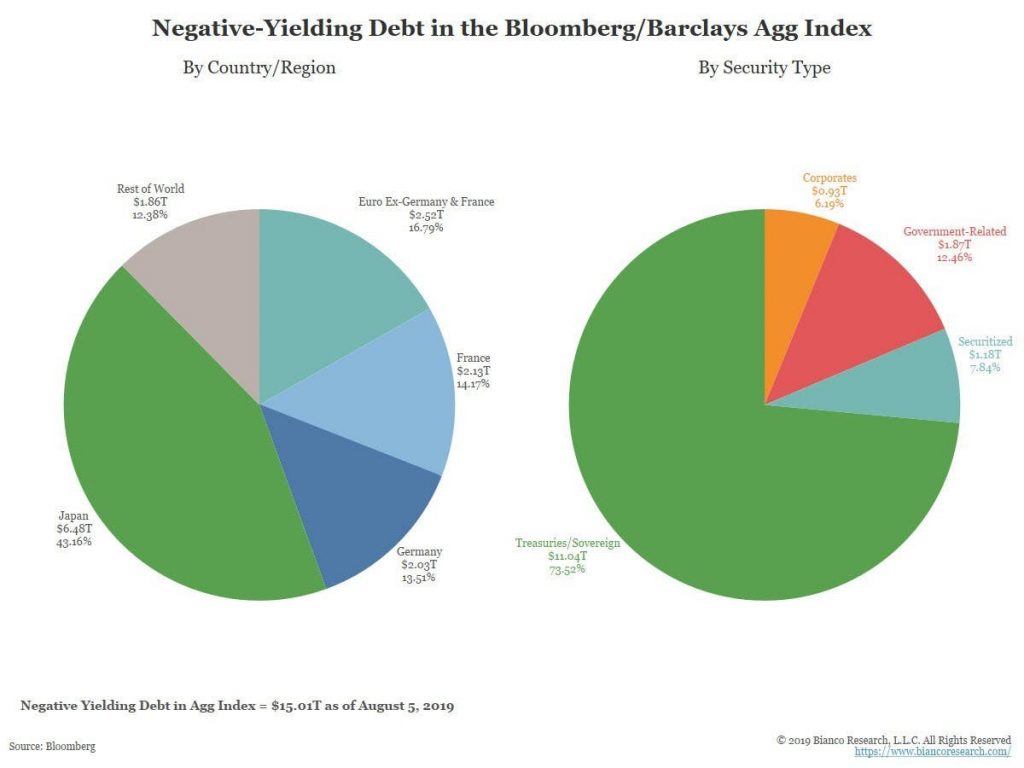

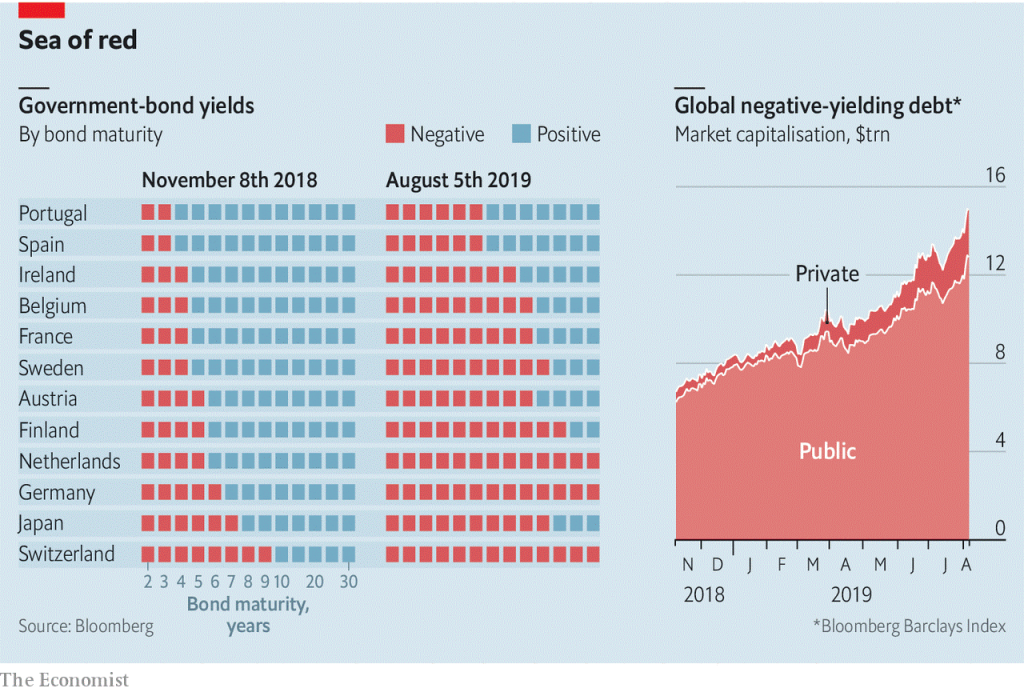

Around ¼ of the global bond market, equivalent to 15 billion (millions of millions of) dollars, currently have negative implicit return rates:

These rates are negative in almost every country in the world, especially in Europe and Japan, mostly for government bonds and equivalent high quality investment grade corporates. The U.S. is one of the few advanced countries with no negative rates of return.

This means that investors who hold them to maturity will end up getting less money than they paid for them, even including interest.

How can a bond have a negative yield? It starts when an investor buys a bond for more than its face value. If the total amount of interest the bond pays over its remaining lifetime is less than the premium the investor paid for the bond, the investor loses money and the bond is considered to have a negative yield.

Interest rates – Long-term interest rates – OECD Data

Money has value and a cost (inflation plus more risk), so it doesn’t make any sense to invest in negative interest rates

The money we have, and it was hard to earn, has value. It has value today, for consumption and savings, and tomorrow, to safeguard against income shortages and/or more consumption.

The value of money should grow at least to the rate of inflation. That’s the only way the money keeps its real value and allows us to buy the same things today and tomorrow.

When we lend our money to someone, to a bank (through deposits) or to a government or to a company (in a bond), the value of money not only has to overcome inflation, but pay us from the cost of risk, that is, the possibility of not receiving the promised money back.

So, the value or the cost of the money we lend must be equal to inflation plus the credit risk insurance premium.

Thus, negative implicit rates of return do not make economic sense, and are not even common sense.

Lending money and thinking that what we will receive from interest payments and capital in the end is less than the amount we lent, is not rational or logical. Especially in case this reality persists for a long period which seems to be the current situation.

How did we get to so many trillions of bonds at negative rates?

Basically, for four reasons:

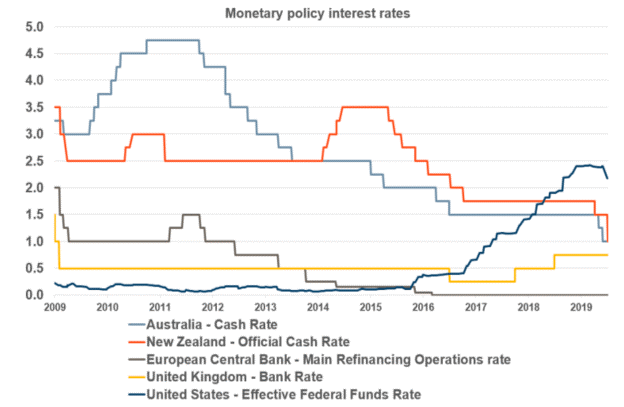

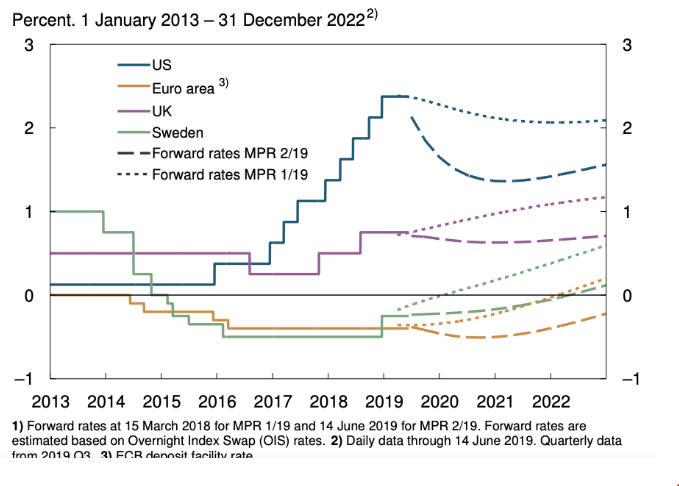

- Because after the great financial crisis, central banks have sought to continually stimulate the economy and make it grow by creating more favourable financial conditions for granting credit to private individuals, companies and governments, by setting their benchmark rates at such low levels that they reached a negative ground and buying gigantic amounts of treasury and corporate bonds;

- Because pension funds, insurers and other financial institutions are either regulated or want to hold a share of their funds invested in safer assets, and are available to pay a premium and can withstand the loss because they need the reliability and liquidity provided by the treasury or corporate bonds with higher credit quality rating;

- Because banks receive more deposits than they grant credits to customers, accumulating excess liquidity, which is invested in bonds and other treasury and corporate bonds;

- Because mutual funds with bond allocations also have to observe and comply with their investment policies every instant, and they oblige us to invest a significant part of the amounts they manage in these bonds.

We reached this situation and we are still in it and everything indicates that we will stay for a while longer. We are here because according to some we need to invest in safer assets due to fears of a sharp growth breakdown or recession, with all issues linked to the US/China trade war, Brexit, Hong Kong, Italy, etc. For others, namely the monetary authorities, because the negative interest rates set by the central banks are the only way to avoid the relapse of the economy and avoid deflation, maintaining adequate growth paces.

But as far we as investors are concerned do we really need to lose money, because that’s what this is all about.

Who wins and who loses?

Besides the implicit negative rates of return rates do not make sense, they also do nothing good to the economy:

- Because they cause a bad allocation of resources. There are investment projects that are only viable because the rates are negative;

- Governments win because they can spend more money and don’t make the necessary reforms because they save on financing costs. Households with little economic capacity can increase their indebtedness;

- Debtors win, and savers pay. The debt grows and the savings of households, businesses and governments decreases;

- Pensioners and retirees see their life deteriorating. They projected to live with a capital in a context of risk-free interest rates, treasury bonds, from 2% to 3%. Today, these rates are negative. They live frightened and retract consumption;

- Investors become even more fearful, feeding the vicious circle. They reduce allocation to stocks and increase bonds. They don’t want to lose at all cost.

So, if we lose as investors, what should we do?

Knowing that it makes no sense to invest in medium and long-term negative rates of return (which is the horizon that matters to us), the choice and decision between the various hypotheses is not at all easy:

- Switch investment in bonds at negative rates to an increase in investment in bonds with positive rates or even in shares. This means an increase in risk and a change from the central and personal investment allocation, which is inexplicable in any situation but mostly of possible risk of economic slowdown and recession;

- Take the opposite decision, i.e. invest more than usual at negative rates such as refuge and protection for eventual recession and crisis in the markets or in an ultraconservative attitude. It doesn’t make sense because we lose money and we don’t know or guess when and even if it will change;

- Go somewhat halfway, i.e., transfer these investments to savings, time and sight deposits at almost zero rates. It has the same drawback as previously mentioned with the aggravating factor that savings do not yield the same as investments.

Thus, what should be done is to maintain the normal, central and personal, diversified and balanced allocation of investments. What we lose in the bonds returns, we expect to be compensated by gains in equities returns and vice versa, and we are managing the investment risk.

If we can maintain discipline, even in these erratic and even irrational situations, we will be better!

Bringing the money under the mattress is not a solution, as well the increase in risk. Sooner or later the market will revert to the mean. As we shall see in another post, a change in allocations can only be justified by a change in personal situation or in a very few totally abnormal economic and market circumstances, such as assets risk premiums mispricing.