What is the recency or short memory bias?

How the recency or short memory bias manifests in investments?

How to overcome the bias? Nothing is as good as you think or as bad as it looks!

What is the recency or short memory bias?

The literature and studies show that this is one of the main if not the greatest behavioural bias. We have a short memory. We want everything immediately, for now. We live in the moment, yesterday and today. We forget the past and leave the future for later. We are carried away by the waves of the immediate, the present, the recent, and the very recent past. We forget past and lived experiences, told or history. We are short-sighted, we don´t see things in distance.

Recency bias is the main type of cognitive error that happens to the human brain. Recency bias occurs when people more prominently recall and emphasise recent events and observations than those in the near or distant past.

Recency bias is a cognitive bias that favours recent events over historic ones. A memory bias, recency bias gives “greater importance to the most recent event”, such as the final lawyer’s closing argument a jury hears before being dismissed to deliberate.

You probably have a very good memory of the things you learn last or more recently. Usually, one should also have a good memory of the first things that were learned. The most difficult information to retain is information in the middle of the learning session.

How the recency or short memory bias manifests in investments?

It is one of the mistakes that plagues many investors, analysts, and investors. The human mind tends to remember the recent data that is happening in our lives and to forget what happened a long time ago.

Humans have short memories in general, but memories are especially short when it comes to investment cycles.

During a market cycle on the rise, people tend to forget the downmarket cycles.

During a bull market, people tend to forget about bear markets. As far as human recent memory is concerned, the market should keep going up since it has been going up recently. Investors therefore keep buying stocks, feeling good about their prospects. Investors thereby increase risk taking and may not think about diversification or portfolio management prudence.

Then a bear market hits, and rather than be prepared for it with shock absorbers in their portfolios, investors instead suffer a massive drop in their net worth and may sell out of stocks when the market is low.

Thus, recency bias can skew investors into not accurately evaluating economic cycles, causing them to continue to remain invested in a bull market even when they should grow cautious of its potential continuation, and refrain from buying assets in a bear market because they remain pessimistic about its prospects of recovery.

Buying high and selling low is, of course, not a good long-term investing strategy.

Nor is it to ignore one of the greatest historical evidence of the performance of the stock markets consisting of the reversal to the mean, which is both the cause and consequence of the effect of this bias.

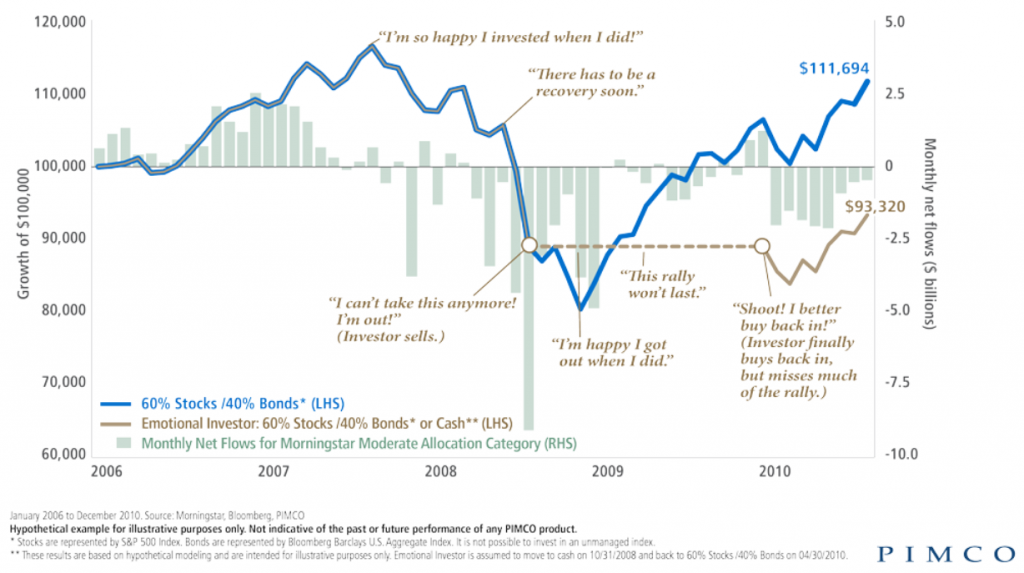

The following chart by the world’s leading manager PIMCO shows the evolution of the S&P 500 index and the net flows invested in this stock market between 2006 and 2010, and seeks to express people’s thoughts throughout this cycle:

From the analysis of price movements and volumes of net investment inflows and outflows, it becomes apparent that people buy late in the climb and sell late in the fall, i.e., they buy high and sell low which is precisely the opposite of the goal to be successful.

When the market was close to highs in mid-2007 most people thought about the good they did in buying, looking at the gains. When it fell between late 2007 and mid-2008, a majority though it was a temporary fall. Sales increased significantly with the huge accumulated losses of the second half of 2008 and remained so until the first quarter of 2009, when the market began to recover, with the perception that they did well to sell being afraid that tomorrow it would be worse. Despite the sharp market recovery that began in March 2009, positive net investments only appeared a year later, when the market had already risen more than 30% from the bottom.

Another manifestation of recency or short memory is in the formation of expectations, which has negative effects. In rising market cycles people have very exaggeratedly high returns expectations and are excessively pessimistic in falling cycles. As a result, the high expectations of rising markets usually do not materialize, people feel defrauded even if returns are average and interesting. Pessimistic expectations often do not come true, people have not invested, and normally markets show good and average returns.

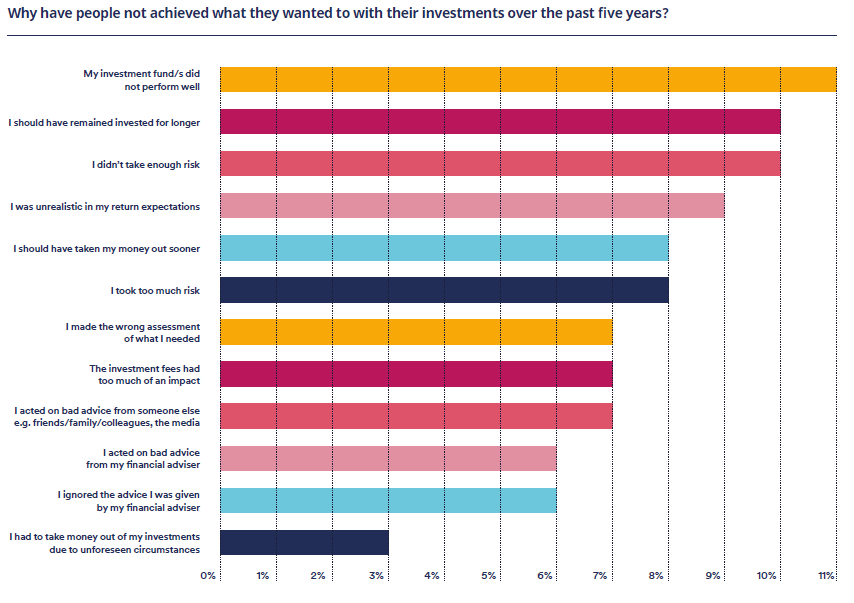

A study conducted by Schroders in 2019 showed this effect:

When asked why they have not achieved the expected results in their investments in the last 5 years, respondents focused on the poor performance of investments, premature divestment, lack of risk- taking, unrealistic expectations, excessive risk-taking, etc., i.e. in general, we find frustrated expectations at the root of all these issues.

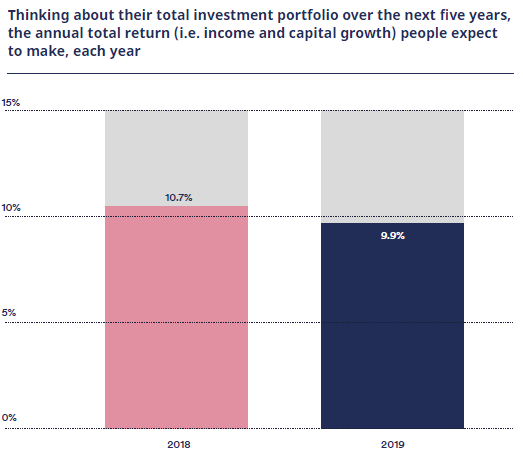

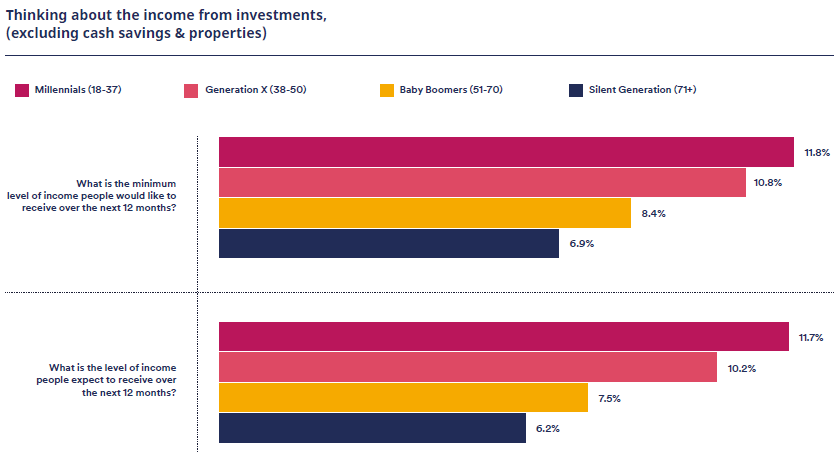

In the same study, when asked about returns expectations, the result was as follows:

The expected returns of 10% per year in the next 5 years for an investment portfolio are certainly very high.

It is worth remembering that the average annual return on US equities and bonds from 1926 to date was 9% and 5% respectively and that portfolios have on average a higher allocation to bonds than equities.

Furthermore, with interest rates so low expectations of future returns are also lower in absolute terms for any of the assets in the medium term.

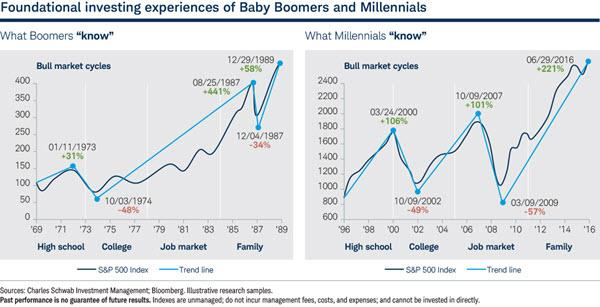

This bias also has implications in terms of how different generations look at investing in stocks.

The behaviour of markets in the first years of financial life or when we make our first investments influences and determines our financial life not only at that time, but also for the years to come. A good experience reinforces a positive attitude towards investing in stocks. A bad experience can keep us away from investing in stocks for years to come or not forever. This situation only aggravates our situation if we keep in mind the importance of the returns of equity investments.

The following graph shows the evolution of markets in the first 20 years of financial life (between the age of 15 and 35 or high school and the constitution of the family) of the Baby Boomers and Millennials generations:

These 20 years in the Baby Boomers occurred between 1969 and 1989, with markets on the rise for long, with valuations of 441% between 1974 and 1987, with the exception of the crisis at the end of the period, but quickly recovered.

On the contrary, the 20 years of Millennials went from 1996 to 2016 and caught two strong crises, the technology bubble of 2000-02 and the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-08, in which gains evaporated with crises and only after 2009 was there an appreciation of 221% until 2016 (and which continued until today).

On the other hand, it is to be expected that younger generations will live more in the present context and the older ones to have a longer historical perspective.

The 2019 Schroders study also precisely showed these differences in generational expectations:

Younger generations have much higher expectations than older ones, which are much more moderate, with differences from more than 10% to between 6% and 8%.

So, not surprisingly, there are studies that show that Baby Boomers have more allocations to equity investments than Millennials, even for the same level of income or wealth.

This reality is serious because it contradicts common sense, since as we know allocation to equities should be higher the younger we are.

How to overcome the bias? Nothing is as good as you think or as bad as it looks!

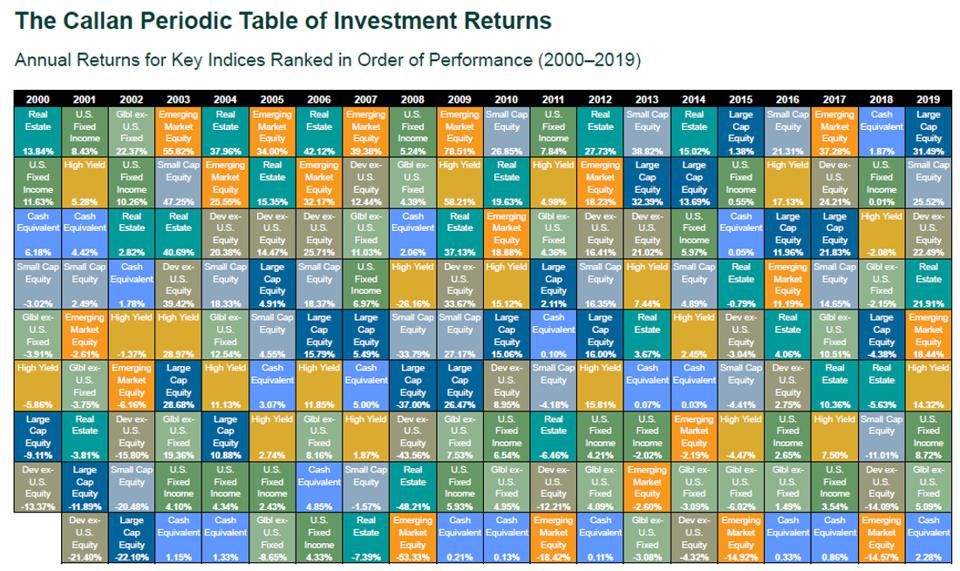

To counteract the effects of recency or short memory bias, many wisely use what has become known as the “periodic table of investment returns”, an adaptation of the periodic scientific table of chemical elements.

The periodic table of returns for the US between 2000 and 2019 was as follows:

In this important table we find the annual returns of the following asset sub-classes in that period: large (dark blue) and small business (grey) stocks, ex-US developed market shares (light brown) and emerging markets (orange), investment grade US bonds (green) and speculative (yellow), ex-US developed country bonds (light green), real estate (turquoise blue) and monetary applications (light blue).

This table clearly shows that assets have cycles and that over time they vary in performance. The most defensive ones such as bonds and monetary investments have better relative performances in crises and much worse in the phases of economic expansion, where stocks are unbeatable.

Because many investors pay no attention to the cyclical nature of asset returns, securities or asset groups that have performed spectacularly in the recent past seem unduly attractive. Often, the best performing asset classes in a year or two years in a row are at the bottom of the table in the following years.

That is the nature of investment: asset classes can move from a “fair” price to becoming overvalued, undervalued, or anywhere in the middle, such as a pendulum swinging from one end to the other. Therefore, it is essential that investors remain disciplined to achieve their financial objectives.

In conclusion, this recency or short memory bias captures us because we don’t put things in a story perspective.

We recall past experiences too late which would have been useful and allowed to avoid mistakes.

We decide to change or do something on impulse without thinking about why we planned or did it differently.

We invest when markets gain and stop investing when markets lose. Meanwhile, we entry in late and buy high and leave late and sell low.

We have a mental structure and memory of 3 years. We forget the previous 5, 10 or 20 years and we do not even want to look at the previous ones. We do not have time, or we think it does not matter.

That is why we insist on saying that: “Nothing is as good as you think or as bad as it sounds!”

https://www.schwabassetmanagement.com/content/recency-bias

https://www.personalcapital.com/blog/investing-markets/how-to-avoid-recency-bias/