How do you distinguish loss aversion from risk aversion?

Main implications of loss aversion in investment decision making

What is loss aversion?

In terms of cognitive psychology and decision theory, loss aversion refers to people’s tendency to prefer to avoid losses than achieve equivalent gains. That is, people would rather not lose $5 than gain $5. Some studies suggest that losses are psychologically twice as potent as gains.

The loss aversion was first identified by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman.

These behavioural science experts conducted an experiment that resulted in a clear example of human bias in relation to losses. The experiment involved asking people if they would accept a bet based on the flip of a coin.

The results of the experiment showed that, on average, people needed to win about twice (1.5x – 2.5x) more than they were willing to lose to continue with the bet (meaning that the potential win should be at least double).

How do you distinguish loss aversion from risk aversion?

In economy and in finance, risk aversion is the behaviour of human beings (especially consumers and investors), who, when exposed to uncertainty, try to reduce this uncertainty.

To better understand the difference, we will use the same example of flipping the coin. In the guaranteed scenario, the person receives $50. In the uncertain scenario, a coin is tossed to decide whether the person receives $100 or zero. The expected pay-out in both scenarios is $50, which means that an individual who is insensitive to risk would not mind accepting the guaranteed pay-out or the bet. However, individuals may have different risk attitudes.

Most individuals are risk averse, although there are those who are neutral and even those who seek the risk (the gamblers).

Main implications of loss aversion in investment decision making

Loss aversion derives from our innate motivation to prefer to avoid losses rather than make similar gains. We cannot eliminate loss aversion, but we must be aware of it so that we avoid making irrational decisions and to help us get more.

The following are some examples of loss aversion that can cause a loss or benefit when we think about our investments:

1. Invest only in safe products that have little or no return and that over time lose value or purchasing power due to inflation.

2. Do not sell a stock below the price at which we bought it just because we do not want to suffer a loss.

3. Sell a stock at a higher price than the price we paid just to take the profit.

4. Prefer to pay life insurance premiums rather than invest for a wealth building goal.

5. Focus on investments that have lost money and ignore other investments.

6. Favour selling winning investments to losing investments for the sole reason of not accepting defeat.

7. Believe that nothing was lost until we sold.

8. Sell to avoid greater losses when the investment rationale tells us to buy more.

Two critical implications: Safety in excess is costly and can be riskier than making risk investments, and all investments have an opportunity cost

You can group all those examples into a set of two critical implications:

– Over-security

– Avoid selling at a loss,

and analyse the results of each.

Over-security

The preference for the safest means that we invest a good part of our financial assets in low risk products and with low or no return, to the detriment of investing in financial assets with interesting returns in the medium and long term:

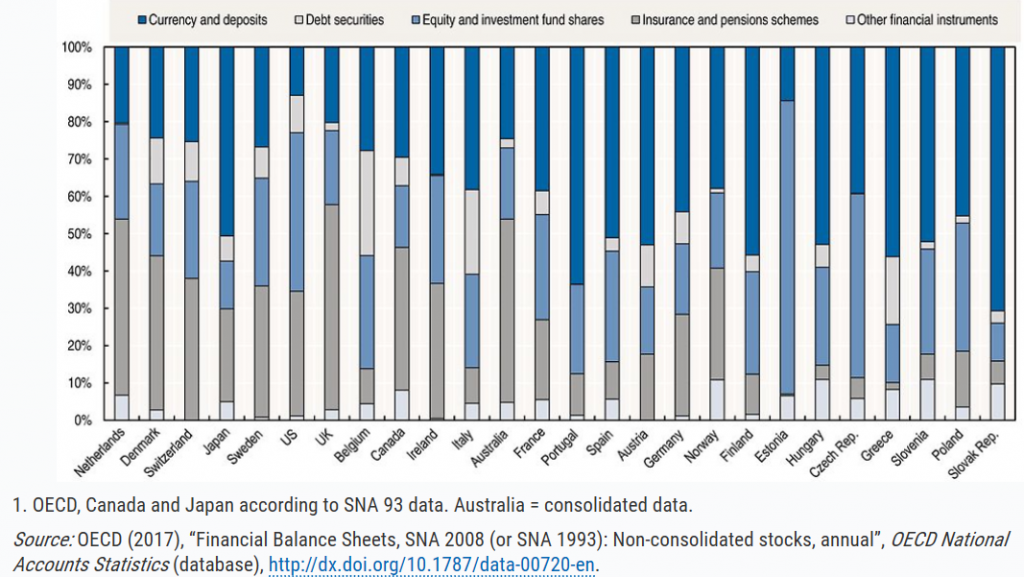

More than half of household assets in some countries, such as Japan, Portugal, Spain, and Austria, place their money in low interest deposits and savings accounts. In most of the others, including Canada, Ireland, Italy, France, Germany, Norway, and Finland, it exceeds 30%. Only in the US do they have small expression, about 10%.

This search for security has a cost. The actual return of these placements is null or negative.

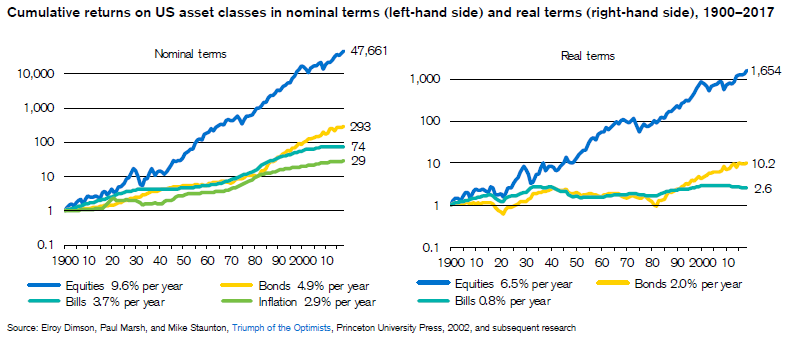

In the US, even the returns of investments in 3-month treasury bills has been marginally positive since the beginning of the last century. Investments in treasury bonds would have yielded a little more, but true wealth creation is only achieved by investing in stocks. And the longer the period the higher the cost.

This attitude can result in complicated situations in the future, especially in the accumulation of assets to live the retirement, the main financial objective that most people pursue, because it limits the ability to create wealth.

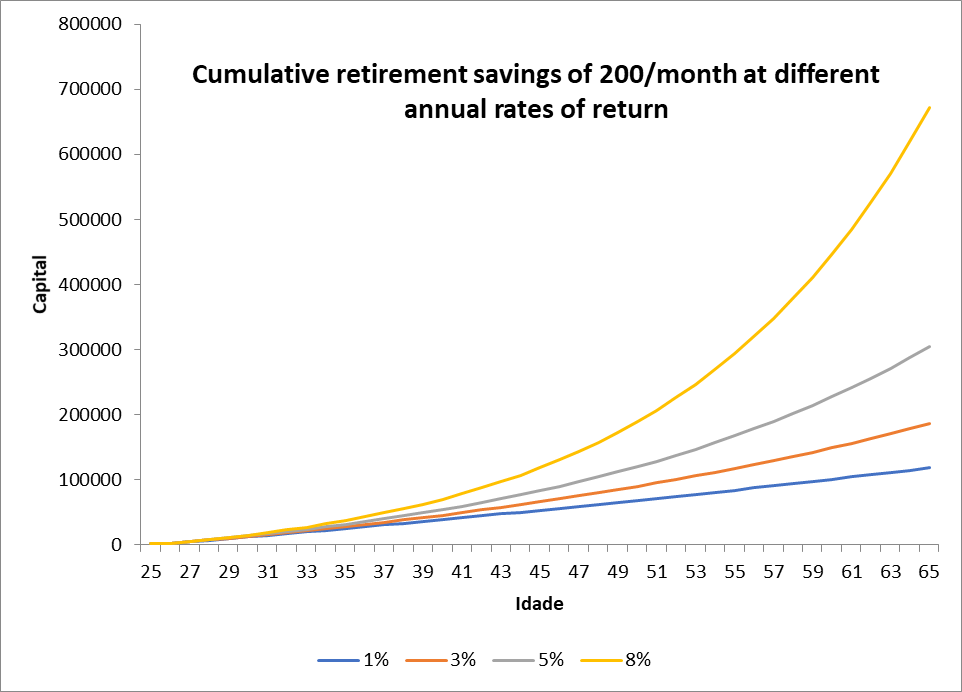

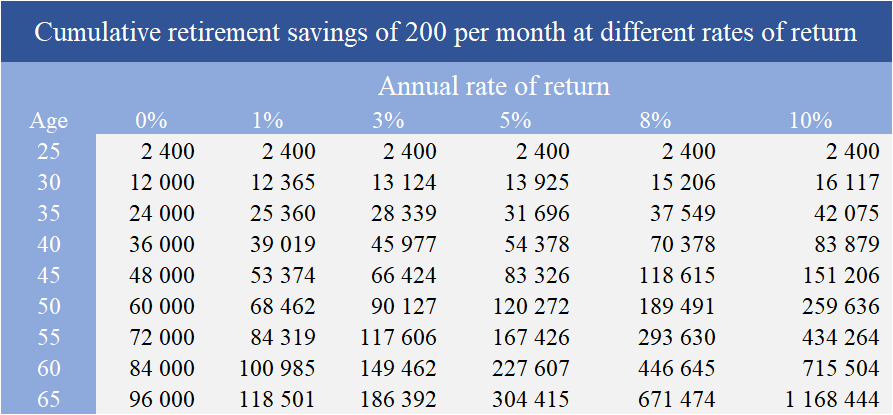

Let us look at an example. If we save 200 per month from the age of 25 to 65 years of age, we will accumulate the following capital depending on the average annual rates of return achieved:

If we place the money in deposits the most likely is that we have rates of return of 1% per year. If we invest in a conservative or prudent mix with a higher percentage of bonds than stocks, we will probably get 3% a year. With a more balanced mix, in proportions of 50/50 we can achieve 5% annual rates of return. If the mix has a strong stocks component, about 75%, and the remaining in bonds, we are likely to reach 8% per year.

In total, our monthly savings of 200 over 40 years are an invested capital of 96,000.

At a rate of 1% they increase almost nothing, rising to 118,501 after 40 years. With a rate of 3% this capital more than doubles, to 186,392 in 40 years. At a rate of 5% the accumulated capital at age 65 is 304,415 and at a rate of 8% the capital increases to 671,474. With a rate of 10% the accumulated capital reaches 1,168,444 (which is possible because the long-term rates of return of large companies in the US were of this order and those of small companies were 12% per year).

We conclude that investing in riskier financial assets in the medium and long term has much higher returns, allowing us to substantially grow our cumulative savings.

Search for excessive security is very costly and can be riskier than taking the risks of investing. Therefore, it is said that not making riskier investments can put life at risk; in other words, to live well we need to take up some level of risk.

Avoid selling at a loss

Often, we stay too long with stocks that record losses and hastily sell the shares they are gaining. This is the old story of the losing stocks will remain for the grandchildren and the investments in which we are gaining we do not let the profits run.

We must be aware that any investment, however low or high value it has, has an opportunity cost.

If we think of it this way we should try, at every moment, to give it the best use. If we are losing and if the prospect is that the trend will continue then it is best to sell and reinvest in another investment. On the other hand, if we are winning and the outlook remains positive, then it is better not to sell, maintain and continue with the investment, especially since it has already given and gone through the work of analysis and decision.

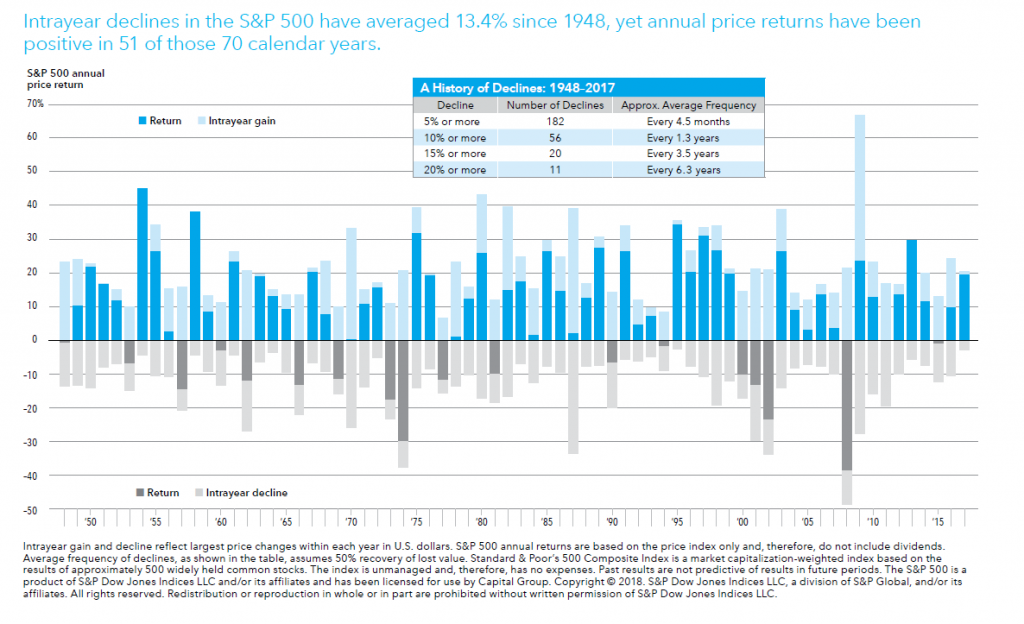

Financial markets, be it stock or bond markets, have ups and downs. In the following chart we can see the annual returns and the largest declines in each of the years, from the main index of the U.S. stock market, the S&P 500, in the period between 1948 and 2017:

Although we had positive returns in 51 of the 70 years (more than 70%), in this period there were average intra-year devaluations of 13.4%, and we had decreases of 10% in almost every year. However, only in 10 years there were annual losses of 10% or more, and throughout the whole period we had average returns of more than 9% per year.

Not selling to lose and sell immediately to win, is a strategy in which one certainly loses money.

https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/loss-aversion/

https://www.behavioraleconomics.com/resources/mini-encyclopedia-of-be/loss-aversion/

https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/trading-investing/loss-aversion/

https://www.schwabassetmanagement.com/content/loss-aversion-bias