Worrying signs. Is the Chinese market investable?

The various prophecies of China’s collapse since 1990

40 years of China’s economic miracle

Paradoxically or not, the stock market has appreciated little in this period, due to the losses of the last 7 years

The explanation for the performance of the Chinese stock market in recent years

Demography, Aging, and the Parallels to Japan’s Lost Decades

Bumps in the liberalisation of markets and setbacks in globalisation

This article begins a series that addresses the topic of equity investment in the Chinese market, from the perspective of foreign investors.

In previous articles we have already developed the size and weight of the Chinese economy in global terms, its enrichment in recent years, as well as its convergence with the most developed countries.

In other articles, we develop the growth of investment in emerging equity markets, as well as their attractiveness, with a focus on the Chinese market.

In yet another article, we delved into the specifics of the structure, functioning and activity of the Chinese stock market.

Despite a remarkable performance of China in economic terms and its stock market, growth has slowed somewhat, and the good valuations recorded until the middle of the last decade have been replaced by significant declines, bringing it to the lowest levels since 2016.

This reality, in addition to clearly showing that economy and markets are different things, raises, above all, the doubt about the interest and attractiveness of the Chinese stock market for foreign investors, the central theme of this article.

Worrying signs. Is the Chinese market investable?

Since peaking in 2016, the Hang Seng stock index, which represents China’s stock market for foreign investors, has lost more than 50 percent after decades of excellent performance so far, in which it far outperformed the S&P 500’s strong gain.

In recent days, the intense selling of Chinese stocks has worsened.

China’s Hang Seng Index has fallen more than 10 percent this month after losing 14 percent last year, while the benchmark CSI 300 index for domestically traded stocks has fallen more than 5 percent as the renminbi depreciates against the dollar.

Foreign investors, who by the end of 2023 had sold about 90% of the $33 billion in Chinese stocks they had bought at the beginning of the year, have continued to sell this year.

The share of foreign investment in Chinese stocks has never been lower today than in recent years.

There are many professionals who say that Chinese stocks are not investable. Is that so?

Have we forgotten the Chinese miracle of the past forty years?

Can we overlook the world’s second-largest economy and the one in which the middle class has grown the most in recent decades?

Could there be any prospect of a parallel or similarity with what happened to the Japanese stock market, where it went from a miracle until 1991 to a precipitous fall by 2015, followed by a sustained recovery to today’s highs?

What are the problems, what changes are taking place and what issues are still to be resolved?

The various prophecies of China’s collapse since 1990

Since the beginning of the Chinese economic miracle, there have been multiple and constant prophecies that predicted the end of the month, such as:

“1990. The Economist. China’s economy has come to a halt.

1996. The Economist. China’s economy will face a hard landing.

1998. The Economist: China’s economy entering a dangerous period of sluggish growth.

1999. Bank of Canada: Likelihood of a hard landing for the Chinese economy.

2000. Chicago Tribune: China currency moves nails hard landing risk coffin.

2001. Wilbanks, Smith & Thomas: A hard landing in China.

2002. Westchester University: China Anxiously Seeks a Soft Economic Landing

2003. New York Times: Banking crisis imperils China

2004. The Economist: The great fall of China?

2005. Nouriel Roubini: The Risk of a Hard Landing in China

2006. International Economy: Can China Achieve a Soft Landing?

2007. TIME: Is China’s Economy Overheating? Can China avoid a hard landing?

2008. Forbes: Hard Landing In China?

2009. Fortune: China’s hard landing. China must find a way to recover.

2010: Nouriel Roubini: Hard landing coming in China.

2011: Business Insider: A Chinese Hard Landing May Be Closer Than You Think

2012: American Interest: Dismal Economic News from China: A Hard Landing

2013: Zero Hedge: A Hard Landing In China

2014. CNBC: A hard landing in China.

2015. Forbes: Congratulations, You Got Yourself A Chinese Hard Landing.

2016. The Economist: Hard landing looms for China

2017. National Interest: Is China’s Economy Going To Crash?

2018. CNN: Forget the trade war, China’s economy has other big problems

2020. Economics Explained: The Scary Solution to the Chinese Debt Crisis

2021. Global Economics: Has China’s Downfall Started?

….

Yet it’s already 2023 and China’s economy is still going strong.”

40 years of China’s economic miracle

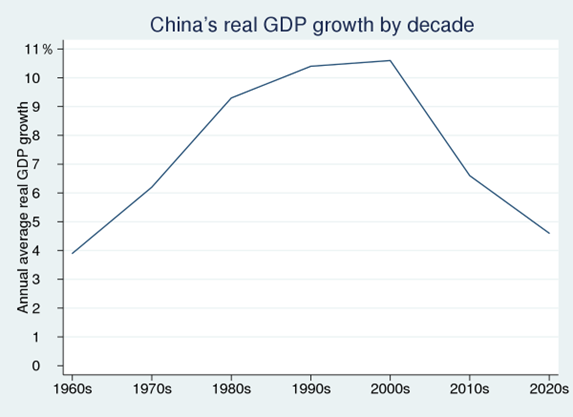

The Chinese economic growth initiated by Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms between 1978 and 1992 aimed at the creation of the socialist market economy was remarkable:

Over the past forty years, China’s real GDP growth has exceeded more than 7% per year, standing above 10% between 1980 and 2000.

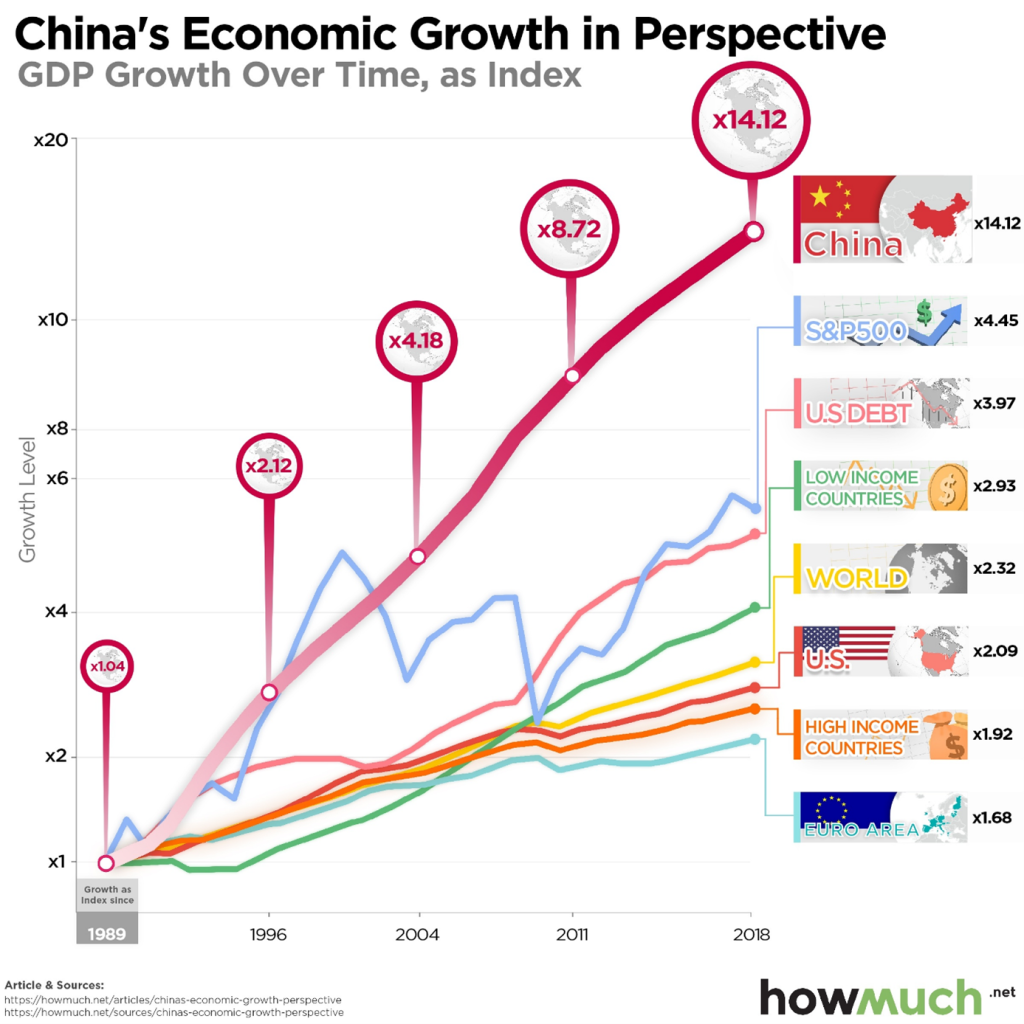

This progress is even more impressive when we compare China’s economic growth with the growth of other countries, or other financial benchmarks:

Paradoxically or not, the stock market has appreciated little in this period, due to the losses of the last 7 years

In 1992, the Chinese stock market was created and developed, which performed excellently until the middle of the last decade:

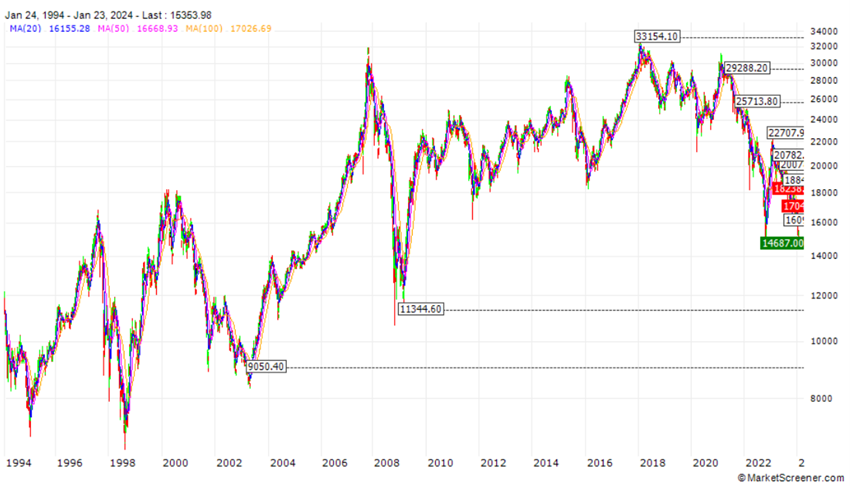

The Hang Seng went from 12,000 points in January 1994 to 33,000 in 2016, almost tripling.

However, starting in 2016, following the slowdown in economic growth, the Chinese stock market began to fall, losing almost 50% of its value to date.

The Hang Seng is at 14,600 points at the start of 2024, less than 30% above 1993 levels, which represents an appreciation of about 1% per year over the past 30 years.

The other major Chinese stock market indices, such as the Shanghai Composite and the MSCI China, performed similarly.

To the surprise of many investors, while China’s GDP grew at more than 9% per year, its stock market appreciated little in this period!

China is one of the clearest proofs that the economy and markets are different realities.

That said, the main question is whether the poor performance of the last 7 years is a sign of a wrong prognosis, or is it something deeper and more structural.

The explanation for the performance of the Chinese stock market in recent years

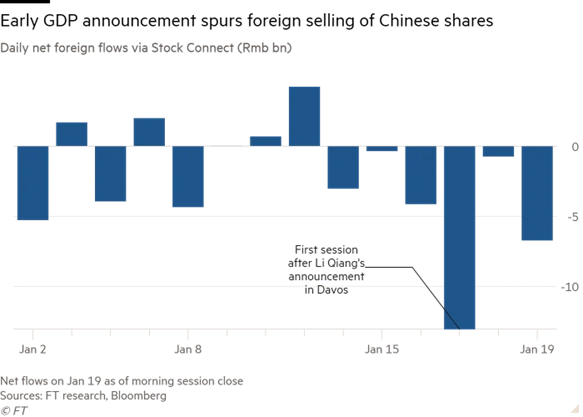

On January 17, when China’s economic growth rate of 5.2% in 2023 was announced, the Chinese stock market had one of its worst days, devaluing 4%. Some shares of large companies fell close to 10%.

Growth of 5% a year would be exceptional for any developed economy.

For China, it is not enough. For decades it has grown at 10% per year. In that time, the Chinese stock market has performed formidably.

In the last 6 years everything has changed!

At first, it was thought that the reason was the overly restrictive Covid policy.

Now we know that it doesn’t. The reasons are deeper and more structural.

#1 Slowing economic growth

The negative performance started 5 years ago and seems to have no end.

It is intrinsically linked to economic growth.

As we saw in a chart above, China’s economic growth began to slow from 2000 onwards, from 10% a year to 5% today.

Obviously, it was difficult to maintain that pace for a long time, even due to the change of starting base, but the slowdown was significant

So what explains this sharp slowdown in growth?

#2 Exhaustion of the economic development model based on public investment

The model of economic development that has been so successful in the last forty years has been exhausted.

Dependence on public investment, managed by state-owned banks and local government authorities, which is largely directed at the construction sector, worked for many years but eventually broke down due to inefficiencies and low productivity.

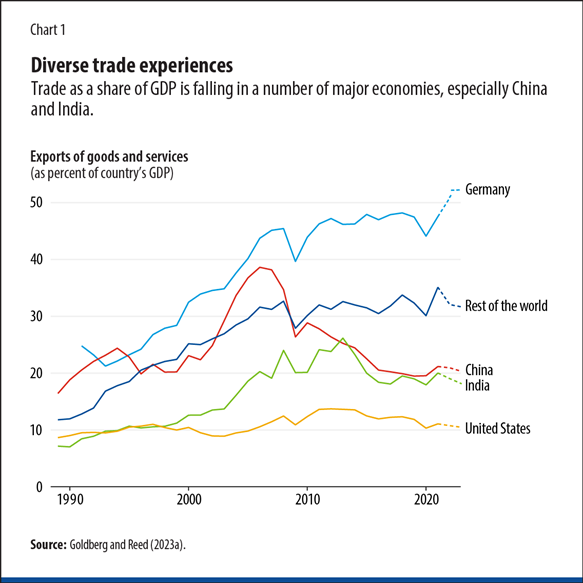

The second major lever was the development of international trade, exports and imports, based on the use of cheap labour and the growth strategy along the value-added chain of products.

The virtuous circle of GDP growth, urbanization, construction burden, rising real estate prices, and rising household wealth has gone from positive to negative.

It opened fractures with the bankruptcies of construction companies, falling real estate prices, declining wealth, and rising unemployment.

We have gone from a virtuous circle to a vicious circle.

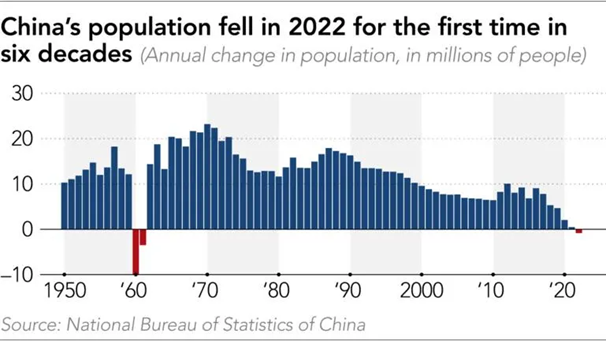

#3 Demographics, aging, and the parallels to Japan’s lost decades

China’s demographic evolution, and especially ageing, pose serious challenges to economic development, bringing to mind what happened to Japan’s lost decades since 1991:

#4 Bumps in market liberalization and setbacks in globalization

China has oscillated in its conception of a socialist market economy, in its various reformist dimensions, from agriculture, industry, commerce, science, technology and the military.

We have seen Deng Xiaoping’s opening up to foreign investment, followed by a rapprochement towards a more liberal model with Hu Jintao, up to Xi Jinping’s greater state and central control.

The process of creating and developing the Chinese capital market was driven by Deng Xiaoping, deepened by Hu Jintao, and even by Xi Jinping in the initial phase.

However, when the Chinese stock market bubble burst in 2015, Xi Jinping used state forces to solve the problem and his promise of economic reforms was stalled.

The state began to interfere in private companies (and in some cases to persecute and prosecute many of their top managers), which generated suspicion and drove away many foreign investors who questioned the stability of the market.

At present, there are times when the orientation is towards greater openness and liberalisation, which are interspersed with others when the authorities seem to want to put a brake on the development of private initiative.

In short, there is a lot of reformist political vagueness in the socialist market economy model, and nationalization tends to override openness to private initiative.

At the same time, we have witnessed the setback of the globalization process, and the advances of protectionism, with the war over economic and geopolitical hegemony between the US and China.

Since 2016, international trade has been decreasing, which directly affects exports, one of the main components of China’s economic growth model.

At the same time, we also have the confrontation between these powers for the protection and hegemony of domains that extend from technology, telecommunications, smart chips, to rare minerals, electric vehicles, solar panels, etc.

China’s bid to assert itself as a world hegemonic power has also brought it many costs.

China’s foreign investment to assert its economic and geopolitical power has been enormous. Just count the amounts invested in the Silk Road, in emerging economies around the world, in Asia, in Central and South America, and in Africa.

China presents itself as an advocate of multipolarity, but in some cases shows traits of bipolarity, similar to the US.

China’s stance on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the two-year-old war is a case in point.

There are those who say that this is a neutral position, of which it is not intended to interfere.

However, months before the invasion, China and Russia announced a very strong partnership, as strong as steel, and the truth is that China continues to feed Russia’s defense that its discourse is aligned with its interests.

Is it a multipolar or bipolar attitude, the consequence of a confrontation between democratic and autocratic regimes?

The purpose of this series of articles is to assess the situation in China to understand whether the Chinese stock market is investable or not.

After all, in addition to its remarkable growth in recent decades, China is the world’s second-largest economy (the second-largest in terms of purchasing power parity since 2016), upper-middle-income, an industrial leader, exporter and consumer, the largest trading partner, has the largest workforce (highly skilled and low-wage) and highly developed infrastructure. and it’s strongly innovative.

All these factors make China very competitive at the global level.

This central question of the attractiveness of the Chinese market is very pertinent because, as we know, investing well means diversifying risks, doing so, above all, in the world’s largest economies and companies, and privileging those that are world leaders and consumer goods, in order to put the economy to work for us.