The bias of the narrow framing in investing

How can we protect ourselves from this bias?

What is Narrow Framing?

Narrow framework is to make decisions without considering all the implications.

The narrow framing bias comes when we focus on the details rather than looking at the overall picture. This framing can undermine our decision-making capabilities because it prevents us from seeing our choices within their context.

The framing effect is a cognitive bias in which people decide on options based on whether they are presented with positive or negative connotations, for example, as a loss or as a gain.

People tend to avoid risks when they are presented with a positive picture but look for risks when they are presented with a negative picture. Gain and loss are defined in the scenario as descriptions of outcomes (e.g., lost or saved lives, patients with treated and untreated diseases, etc.).

The prospect theory, developed by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in 1979, shows that a loss is more significant than an equivalent gain, that a certain gain (certainty effect and pseudo-certainty effect) is favoured over a probabilistic gain, and that a probabilistic loss is preferable to a definitive loss. One of the dangers of framing effects is that people are often given options within the context of only one of the two frames.

In 1981, those academics explored how different phrases affected participants’ responses to a choice of a hypothetical life-and-death situation.

Participants were asked to choose between two treatments for 600 people affected by a deadly disease. Treatment A was predicted to result in 400 deaths, while treatment B was 33% likely to die, but a 66% chance of all dying. This choice was presented to the participants with a positive framework, that is, how many people would live, or with a negative framework, i.e., how many people would die.

| Framing | TreatmentA | Treatment B |

| Positive | “200 lives are saved “ | “A 33% probability of saving all 600 people, and 66% of not saving.” |

| Negative | “400 people die” | “A 33% probability that no one will die, and 66% where all 600 people will die.” |

Treatment A was chosen by 72% of the participants when it was presented with a positive framework (“200 lives are saved”), falling to 22% when the same choice was presented with a negative framework (“400 people die”).

The bias of the narrow framing in investing

The effect of the narrow framing has been consistently proven to be one of the strongest biases in decision-making.

As a result of the framing effect, investors tend to react to investment options inappropriately. Investors accept or reject a proposal depending on how it is framed. In cases where the result is the same, they will agree to the proposals presented as risky gains and reject those portrayed as risky losses.

This makes investment decisions inaccurate and influenced by bias.

The framing effect can also be used to mislead investors into certain schemes, investment vehicles and companies.

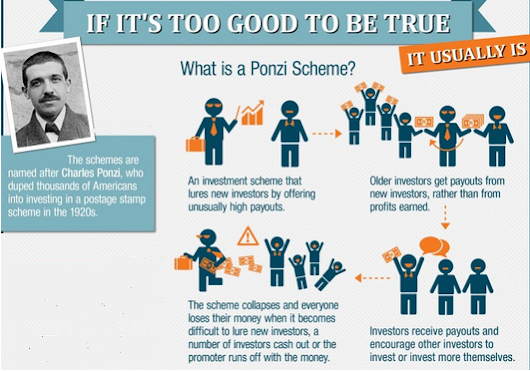

One of the most well-known investment schemes is the Ponzi scheme whereby a respectable manager promises to pay above normal returns to investors that are paid by as ever-growing inflow of money by new investors:

When there is not enough new money coming in to pay the promised returns, the system collapses and investors lose all their money.

Companies frame the information in such a way that their positives are more prominent than usual, as well as the negative points of competitors. This will cause investors to make incorrect decisions, leading to huge financial losses.

When a positive picture is presented to investors, they are more likely to avoid risks. And when the negative picture is presented, investors are more likely to look for risks. It is also important to note that the framing effect increases with age, so older investors are more affected than younger ones.

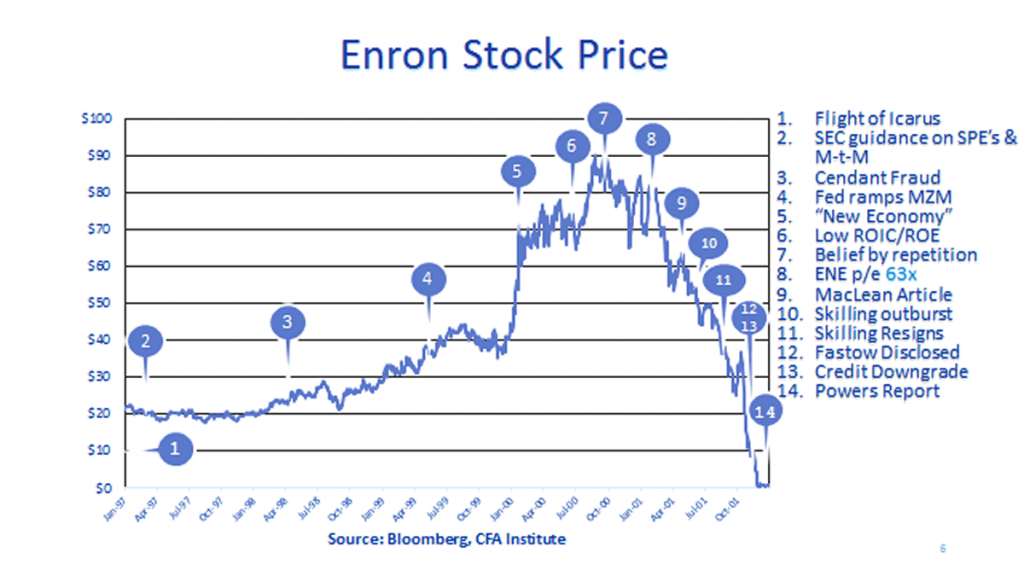

The Enron story is a highly known case-study by academia and financial practitioners:

During the run-up to the technology bubble in the late 1990s, Enron rode the wave and promised to transform the energy business, and even the internet, with bandwidth trading.

The market anointed Enron as a transformative leader. At its peak in 2001, Enron’s stock price reached more than $90 per share, and its market capitalization topped $66 billion.

The company was part of the so-called New Economy, which was light on assets and fast moving. And Enron fulfilled this perception until the early part of 2001. Then, Enron lost its reputation in a wave of scandals, culminating in the company’s spectacular collapse.

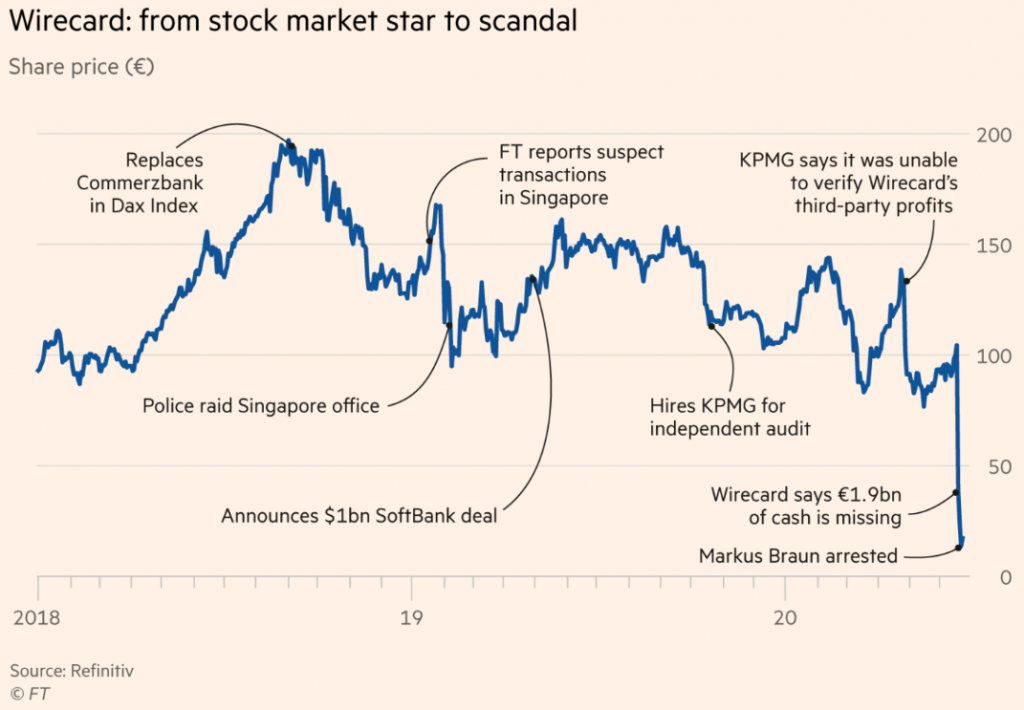

A more recent example is the Wirecard story, a German based payments group that became one of the hottest stocks in Europe while battling persistent allegations of fraud and ended up filing for insolvency.

Wirecard was founded in 1999 in Munich, was listed in 2005 in Frankfurt, entered the banking business and started in a buying spree of companies all over the world, in Europe, North America and Asia.

From 2008 onwards there were several accusations of fraudulent activities constantly rebuffed by the company with the support of its lawyers and auditors.

In August 2018, Wirecard shares hit a peak of €191, valuing it at more than €24bn. The group claimed it had 5,000 employees, who processed payments for about 250,000 merchants, issued credit and prepaid cards and provided technology for contactless smartphone payments.

At the end June 2020, Wirecard acknowledged for the first time the potential scale of a multiyear accounting fraud, warning that the €1.9bn of cash probably does “not exist”. Wirecard says it will file for insolvency.

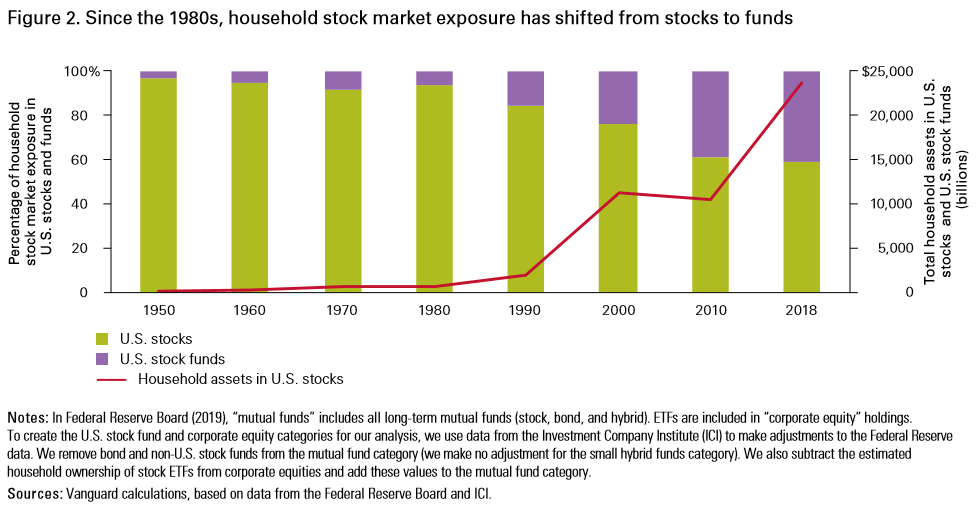

One consequence of the narrow framing is that we select securities rather than choosing to invest in collective funds or investment products that provide us with a more appropriate diversification:

Most US households still prefer to invest directly in stocks than in equity funds, to the detriment of diversification, cost savings and professional allocation and management. However, the trend of the last four decades is clearly an increase in investments via funds.

How can we protect ourselves from this bias?

One of the things we can do as an investor is always challenge the framing. We can reformulate the information we receive and see the impact, if any, that it has on our conclusion. The important thing is to try to activate the logical and reflexive approach to decision making and avoid impulsive and reflective decisions.

For example, any media news, company press release, or analyst investment report can contain many opinions and biases.

We must try to remove any editorial/critical comments and look at only the key numbers and underlying assumptions that drive the assessment. Then come to our own conclusions, rather than being influenced by how information is presented to us.

Regarding financial markets and investments, as well as in much aspects in life, not everything is as good as it seems, not as bad as one thinks!

https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/framing-effect/

https://www.behavioraleconomics.com/resources/mini-encyclopedia-of-be/framing-effect/