We are losing money if the rate of return of our investments does not exceed it

Money and inflation: prices increases, rising cost of living and the purchasing power of money

Inflation is invisible, silent and corrosive. It destroys financial capacity, and the worst thing is that we do not realise it is going on.

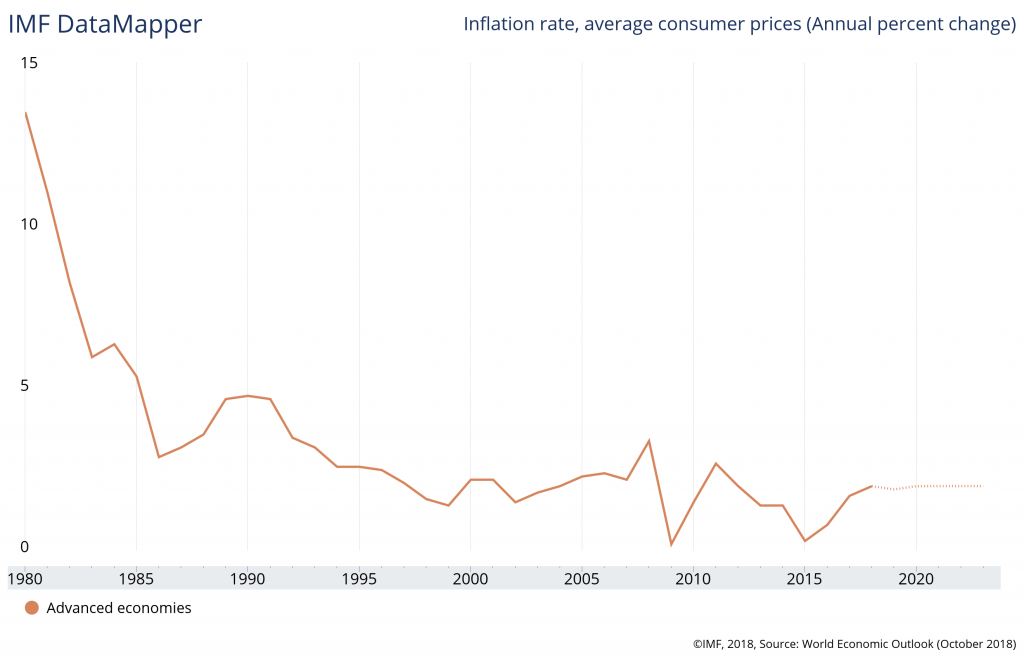

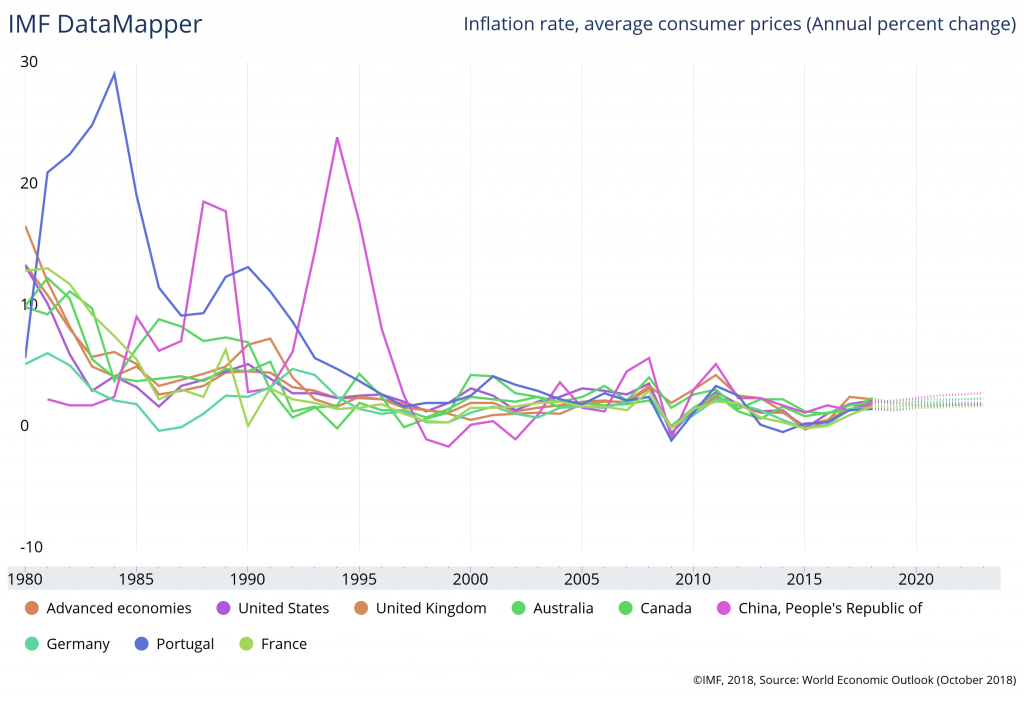

Average annual inflation has been about 3% per year in the developed world in the last decades. If you don’t have investment income greater than or equal to inflation, we’re losing purchasing power

The accumulated inflation is also very useful because it allows us to compare and assess capital between periods in time

The best evidence of purchasing power is the money devaluation caused by inflation (the inverse of the accumulated inflation)

The capital equivalence between different moments in time is even more useful and as it compares money amounts from the present to the future (and vice versa)

Money and inflation: prices increases, rising cost of living and the purchasing power of money

Money is worthless in itself. It is just paper we trust. It’s only worth what we can buy with it.

We need the money to buy the goods and services we need, today and tomorrow. However, the price of goods and services changes day by day. The only way to compare the money we accumulate over time is in terms of purchasing power or the cost of living.

It is the real value of money that counts, that is, when it is adjusted for inflation. The monetary or nominal value matters little.

Even with moderate inflation rates, compared to those in developed countries in normal times, of around 3% per year, the differences of the value of money are higher than we normally think. It’s a fact we have to face!

Inflation is invisible, silent and corrosive. It destroys financial capacity, and the worst thing is that we do not realise it is going on.

Inflation is the generalized rise in prices of goods and services that we need and buy, such things as food, clothing, transportation, housing, health, education, etc. Throughout our lives we will need to buy these goods and services.

We make savings to improve our financial capacity, that is, to increase the value of our wealth. We want, at the very least, to preserve our standard of living, although what we really want is more, its wealth growth. For this to happen, our assets must grow at a faster pace than inflation in order to improve our purchasing power and our financial capacity or wealth.

Over time, what matters is not the value of assets in monetary terms but rather their real value (less inflation).

Inflation also determines our choices between consuming today or saving and investing to consume in the future.

Thus, inflation is the minimum level of profitability required for investments

Not counting inflation is a mistake. It’s short sighted and foolish.

Average annual inflation has been about 3% per year in the developed world in the last decades. If you don’t have investment income greater than or equal to inflation, we’re losing purchasing power

The following charts show the annual inflation in advanced economies, in some of the main world economies and in Portugal. Despite the sharp decline of inflation in recent years, the average annual inflation in developed countries is 3%.

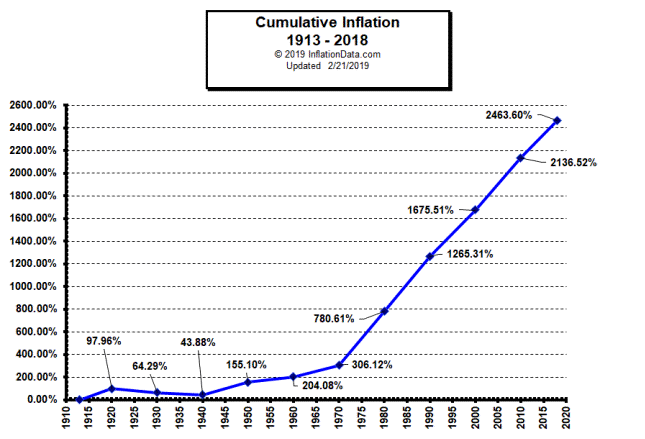

The accumulated inflation is also very useful because it allows us to compare and assess capital between periods in time

Accumulated inflation translates the increase in the cost of living over time. This allows us to perceive and make comparisons of purchasing power at different times.

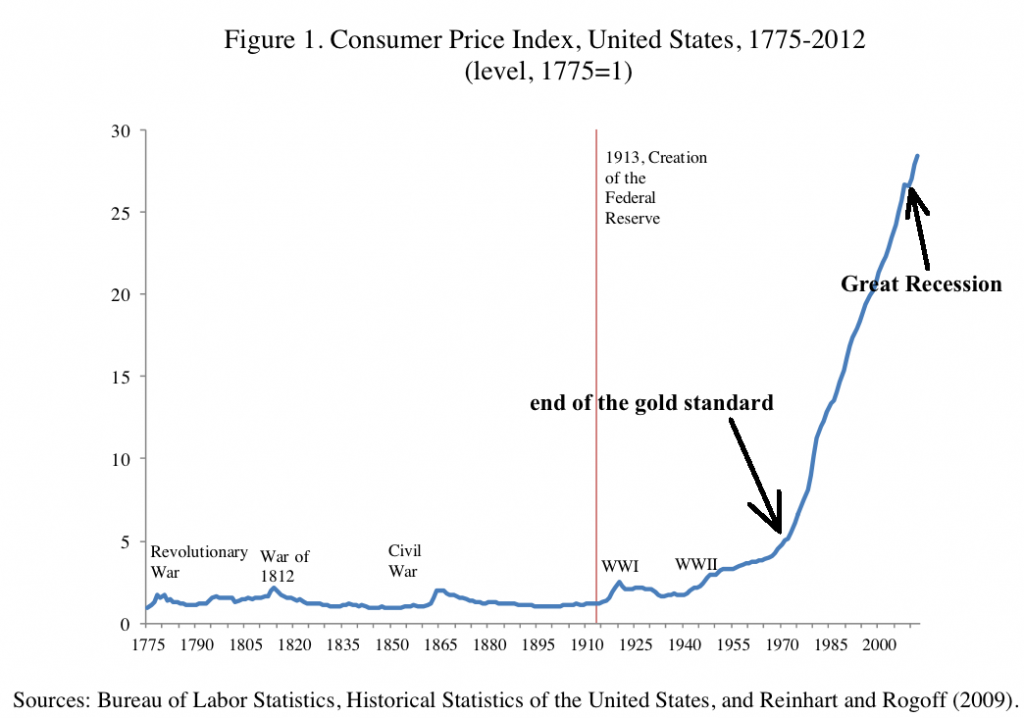

The US example (since 1775 or 1913 according to the charts) is applicable to other countries and geographies because, as we have seen over long periods, the dissonance is small.

Inflation was virtually non-existent until the end of the gold standard in the early 1970s (this is one reason it is said to be essentially a monetary phenomenon). Since then, the average has been 3% per year.

The percentages are easy to see (first chart) but the logarithmic scales (second chart) are more useful for evaluating equal growths at different bases or starting points (going from 1 to 2 is not the same as going from 10 to 11 but from 10 to 20). And to compare values: 1 monetary unit in 1775 equals nearly 30 in 2012.

Source: InflationData.org

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics of the US (2009)

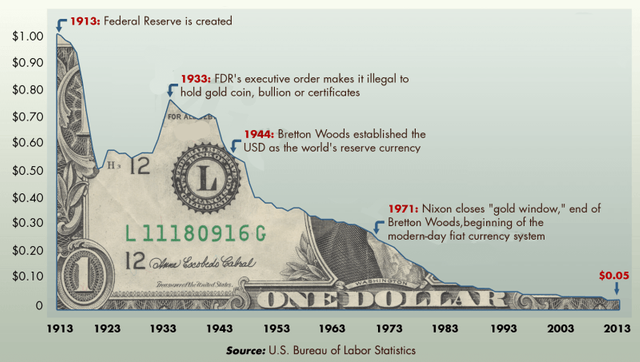

The best evidence of purchasing power is the money devaluation caused by inflation (the inverse of the accumulated inflation)

The loss of the value of the currency caused by inflation is the best evidence of the loss of purchasing power.

A $1 bill in 1913, when Fed was created, was worth only $0.05 in 2012 (-97%), $0.40 in 1945 (-93%), $0.20, in 1975 (-83%) and $0.10 in 1985 (-65%). Today, we buy 30 times less things with that note.

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

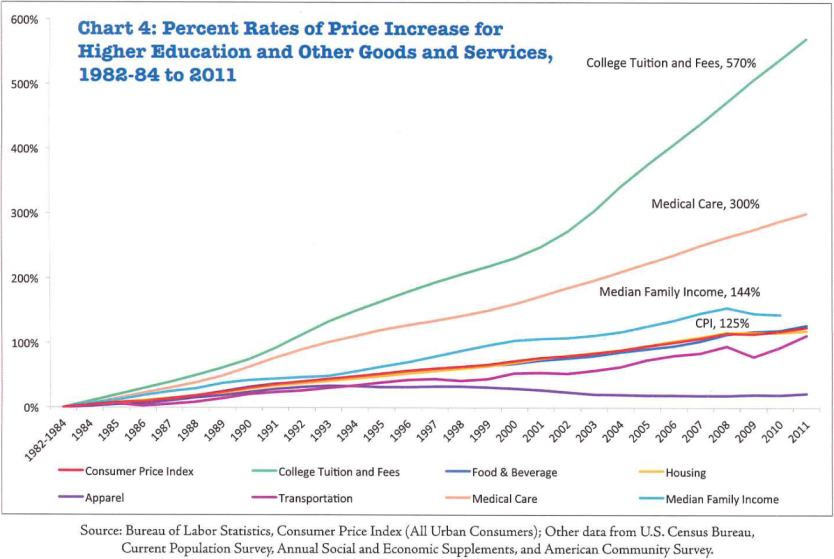

Incomes have grown slightly above inflation, but not for much, less than 1% per year between 1980 to the present day.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index 1982-84 to 2011

There are many who think that future increases in their incomes allow them to enjoy great improvements in their lives. This chart shows that those increases were only marginally higher than inflation. However, the rising costs of some unavoidable and very important expenditures, such as health and education, far outweigh this.

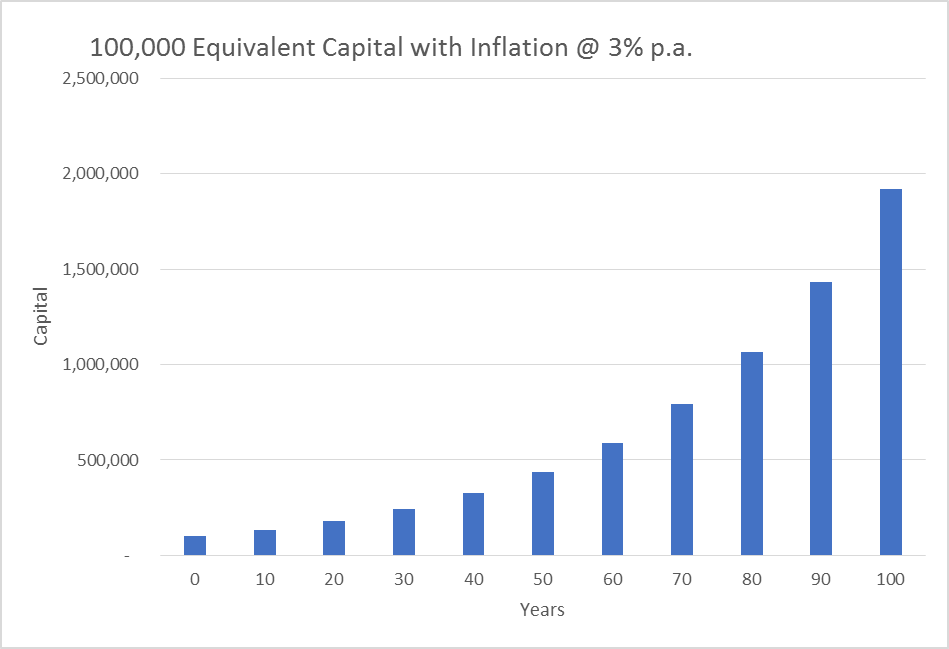

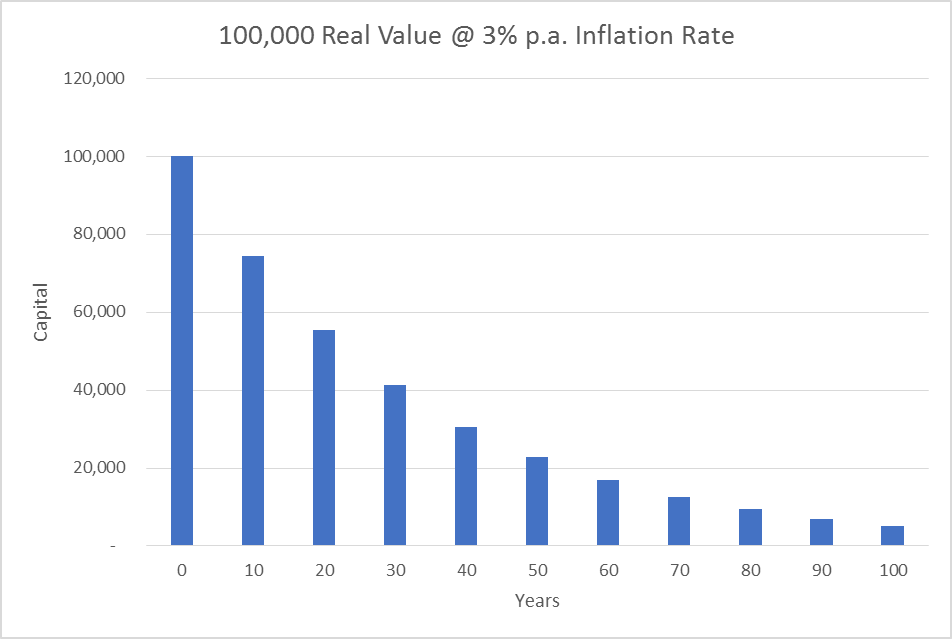

The capital equivalence between different moments in time is even more useful and as it compares money amounts from the present to the future (and vice versa)

Equivalence of capital over time in terms of purchasing power is still more useful and relevant.

With an inflation of 3% per year, a capital of 100.000 today is worth the same than 242.726 the 30 years and 438.391 to 50 years. Another way to look at it, with the same inflation of 3% per year, is that a capital of 100.000 today, devalues itself monetarily to 41.199 in 30 years and to in 22.811 in 50 years’ time.

Just to maintain purchasing power (i.e. not enrich or support the same standard of living) we have to grow our capital in those percentages, and most important, values.

This equivalence is like a ruler or a converter in terms of prices or costs of transferring money in time. It tells us how much capital today is worth in the future, and vice versa.