The context of bond investing has changed, but its importance in investment portfolios remains, contrary to the opinion of some analysts and investment managers

How we decide bond investment allocations

The cycles of bond performance and the attractiveness of the market context

We can and should make small adjustments to asset allocation to market conditions

In the first part of this article we saw the benefits of investing in bonds.

In this second part we will see how we should decide the allocation of our assets to bonds, how we assess the current market context, and whether or not we can make adjustments of the allocation to market conditions.

The context of bond investing has changed, but its importance in investment portfolios remains, contrary to the opinion of some analysts and investment managers

Recent changes in the behaviour of the bond market over the past four decades have posed the question for many investors about the prospects for the performance of this investment for the future.

Since 1980 we have lived through a period of continued decline in long-term interest rates until 2022, which ended with the arrival of high inflation and the inevitability of the imposition of contractionary monetary policies.

It was more than 40 years of what became known as the long “bull market” of bonds, of high and certain yields for bond investment.

In the lexicon of investments were words like “Quantitative Easing” and “Fed put.”

Most managers and investors, including professionals, have not known another reality.

They have become accustomed to this way markets function, adopting it as a rule or a doctrine.

Only recently, and in some cases at great cost, have they begun to realize that this is not so, and that markets change with changing circumstances.

This change happens because the action of the authorities has changed, and this has occurred and is necessary because it is the only way to combat high inflation and return it to adequate levels, which is the main desideratum of the authorities in view of the serious economic and social losses caused by high and uncontrolled inflation.

Bond investments have suffered significant devaluations in the recent past, by more than 20%.

This sharp devaluation is unusual, and in some cases, unprecedented, leading some investors to predict the end of interest in bond investing and the traditional 40/60 portfolio.

They wonder what role bonds play as an element of capital preservation with such sharp declines, as well as as as an element that contributes to diversification, when these heavy losses occur simultaneously in bonds and in stocks.

Our view is different and is based on financial theory, and on the very long-term history of financial markets, not just in the last 40 years.

In our opinion, investing in bonds is a cornerstone in building a balanced investment portfolio, for the benefits we saw in the previous article.

In addition, unlike many, we consider that the current context is very favorable for investment in long-term bonds in developed countries, both in the US and in Europe.

How we decide bond investment allocations

As we have seen in previous articles, the allocations of our investments to the top 2 assets should be decided according to our objectives, the investment term and our investor (risk) profile.

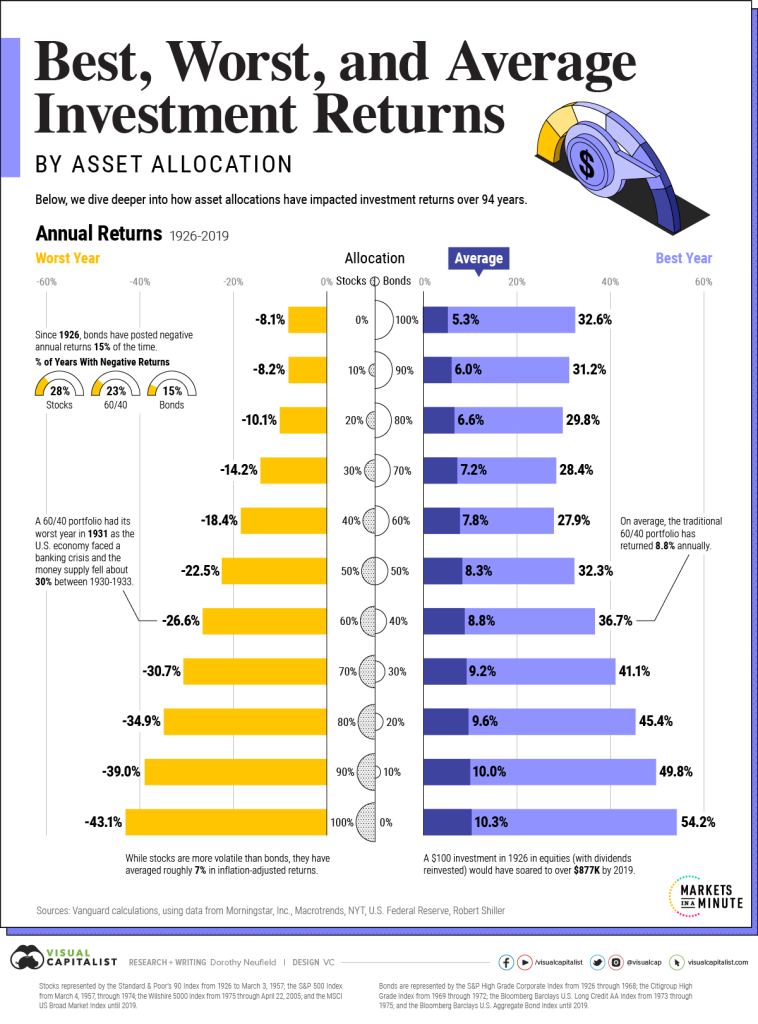

We have also seen that, historically, this asset allocation determines the performance of the investment portfolio by more than 90%, in terms of profitability and risk, so the scale of historical returns in the following chart is useful to position the commitment of this decision in relation to those two elements:

The chart shows the historical annual returns – average, highest and worst – of investment portfolios with a “mix” ranging from 100% of stocks and 0% of bonds up to 100% and bonds and 0% of stocks.

The cycles of bond performance and the attractiveness of the market context

The question arises as to how to assess the attractiveness of market conditions for investment in bonds, and whether the decision to allocate to the mix of shares and obligations that should result from the objectives and profile should remain unchanged or not, in the face of changing market conditions.

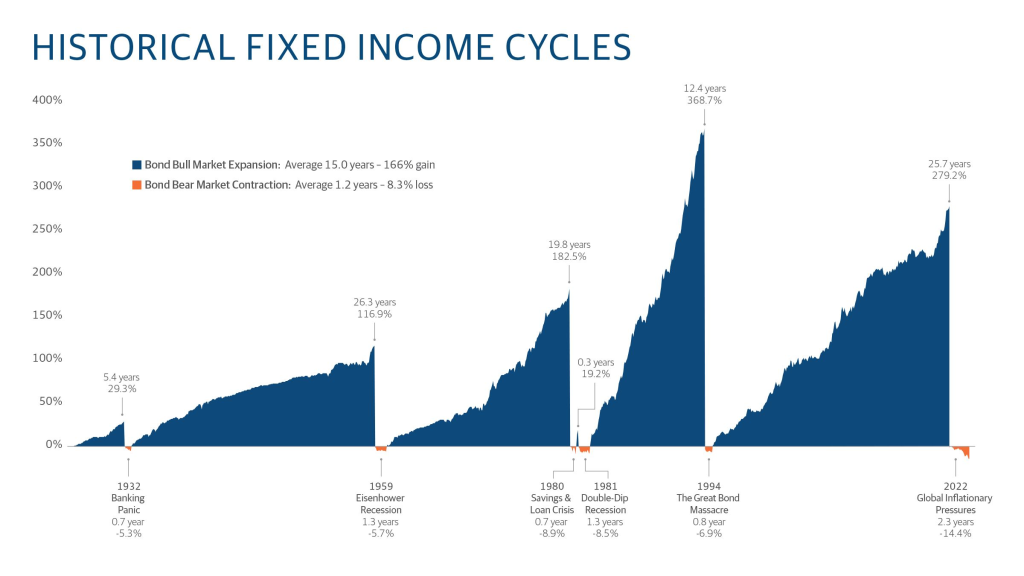

Bond performance also runs for cycles, with periods typically associated with high inflation.

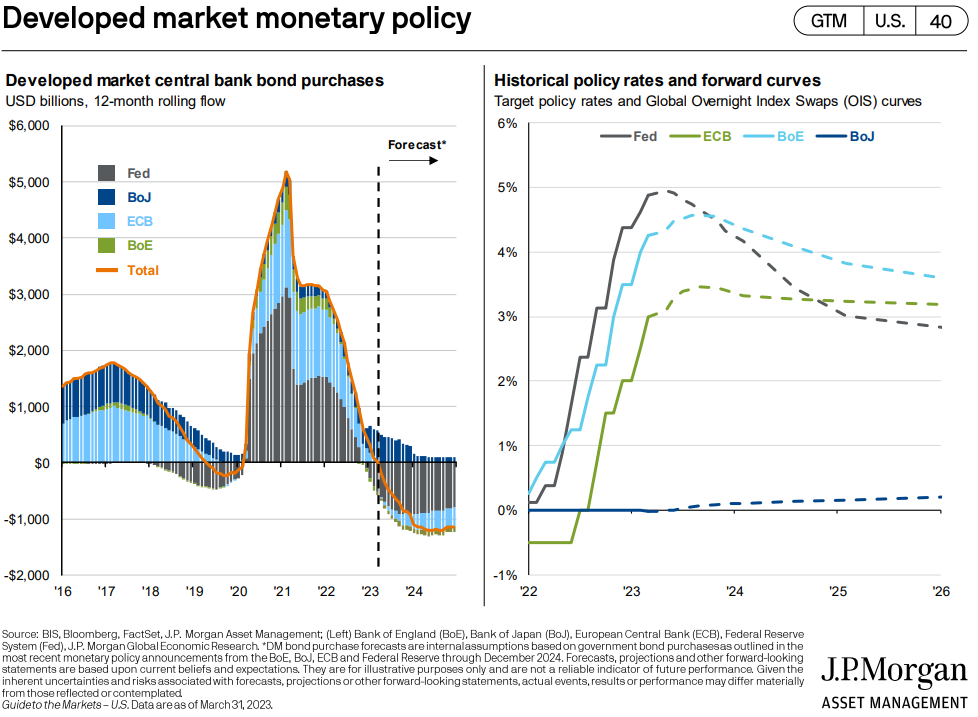

The following chart shows the bond valuation cycles:

We highlight the last cycle, very long and very positive, known for the long “bull market” of bonds that prevailed between 1983 and 2021, and which culminated in the loss of 14.4% in 2022 associated with the change in monetary policy resulting from the fight against inflationary pressures (although here it is split in two, being interrupted by the correction of less than 7%, which lasted 9 months in 1994).

The previous positive cycles were also very long, from 20 to 26 years, but more modest, with cumulative gains of 180% and 110%.

As we have said, historically 90% of the total profitability of the bonds comes from the payment of the coupon, the remainder being derived from capital gains.

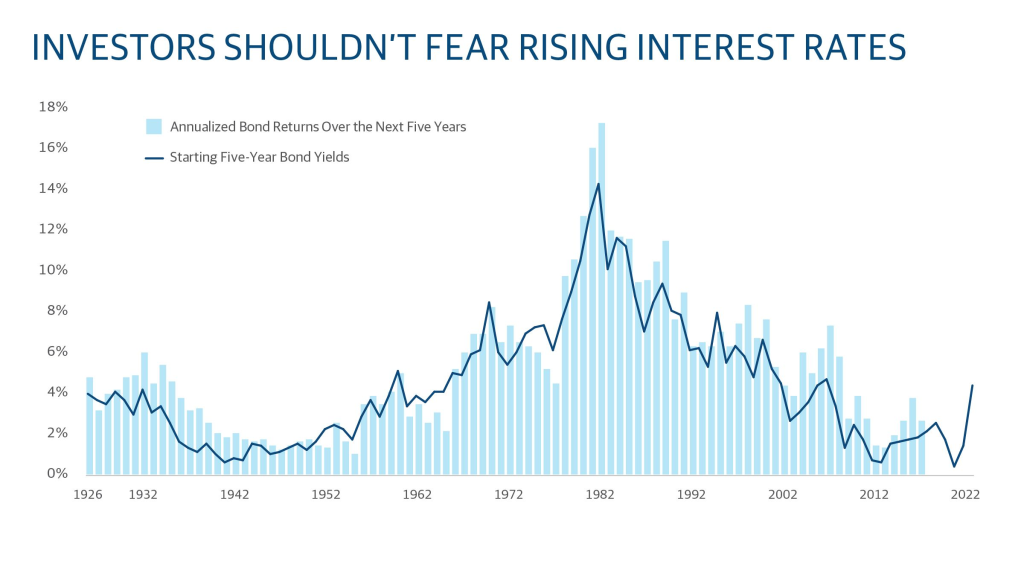

In these terms, a long-term interest rate like the current one, at more than a decade high in the US, can be a very interesting factor.

The following chart shows that long-term interest rates have determined the level of average annual bond yields over the next 5 years:

In our view, the current levels of 10- and 30-year interest rates in the U.S., above 4% per year, which have not happened for more than a decade, are attractive.

In mid-August, implied yields on 10- and 30-year U.S. Treasuries were at levels of 4.3% and 4.5%, the highest since 2011 and 2007, respectively.

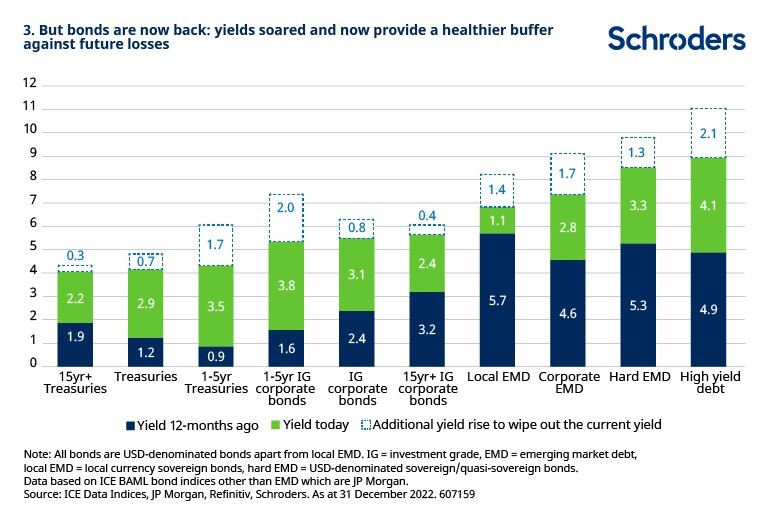

Yields on the investment-grade U.S. corporate bond index reached 5.8 percentile, which had put them in the 91 percent percent since 2008. The spread over the benchmark rate was at 160 bps, placing it historically in the 77% percentile.

This reality is transversal to all investments, which have seen implicit returns increase in the last 12 months:

It is for this reason that we consider that we should maintain our allocation of investment in bonds, contrary to those who opine that investment in bonds has lost interest, either by the end of “Quantitative Easing”, rising interest rates and inflation, or the simultaneous losses in stocks and bonds and the consequent weakness of the contribution to diversification.

Even if there is still some increase in long interest rates in the short term, the effect of an increase of 1%, from 4% to 5% in the total return will be much smaller than that of 1% for the 2%, because we have a coupon of 4% that can be reinvested, and provide a great appreciation of capital through the capitalization of income for a long term.

We can and should make small adjustments to asset allocation to market conditions

Regarding the current attractiveness of bond investment, we go even further, considering that these levels are so interesting that they should prompt an increase in the allocation to bonds for U.S. investors. As we have said, these conditions have not been in place for more than 10 years.

With regard to European investors, we believe that the objective allocation to eurozone bonds should be maintained, as the ECB is still further behind in its programme of raising official interest rates.

In these terms, we consider that the allocation between stocks and bonds can and should be adjusted to market conditions. We must do so in the form of moderate adjustments, nothing drastic.

We should increase exposure to the bond market when the stock market is overvalued, as happened in the tech bubble, or when levels of long-term bond yields are interesting, as they are now.

On the contrary, we should increase exposure to equities when the stock market proves attractive, such as after the 2008 GCF, the end of 2018, and the strong stimulus to combat the pandemic in mid-2020, or when the bond market is uninteresting, as in the period of near-zero or negative interest rates, between 2017 and 2020.

It is good to remember that negative interest rates are nonsense, to make repay those who lend, as we said, at the time.