Reason and logic are the most important decision factors do act. We only do what makes sense to us and has a purpose. Only then comes how, how much, in what, when and where… 5 great reasons to invest in bonds

#2: Because bonds are low risk and far less risky than stocks

#3: Because we have deposits and savings in excess that do not yield anything material, that would have better returns with small risk if they were invested in bonds

#4: Because diversification of investments between stocks and bonds allows us to balance returns and risk, and to adjust them to our personal profile

#5: Because we need the stability of the income of the bonds, and above all its mitigating effect of the risk of investments in stocks

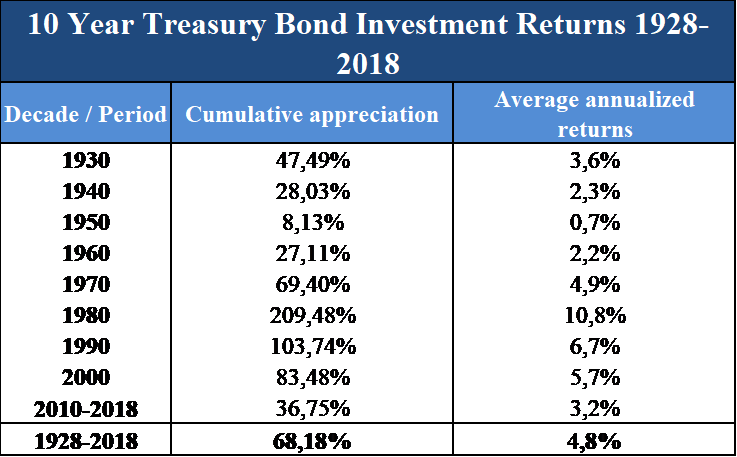

#1: Because bonds are a financial asset with returns above inflation, albeit much lower than the returns of stocks

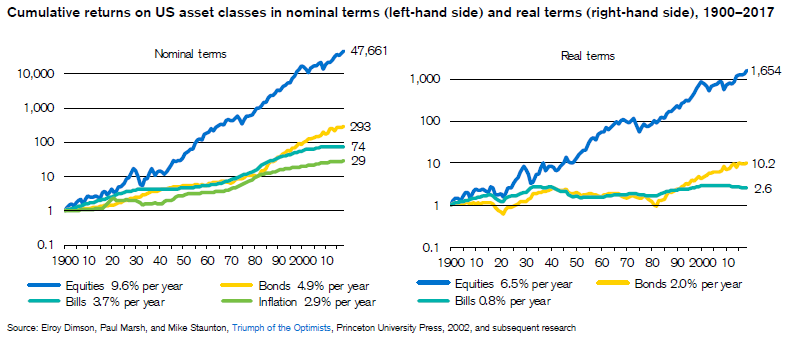

The following chart shows the average annual return of investments in stocks of large companies, 10-year Treasury bonds and 3-month Treasury bills for the U.S. in the period 1900 to 2017:

The average annual return of Treasury bonds was 4.9%, in nominal terms, and 2.0% in real terms.

These values fall very short of the annual average return rates of stocks of large companies, 9.6% and 6.5%, in nominal and real terms, respectively.

However, they outweigh the rates of return of Treasury bills and the inflation rate, 3.7% and 2.9%, in nominal and real terms, respectively (which constitute one of the main short-term investments made by commercial banks, and work as a reference for fixing the upper threshold of deposit rates and savings accounts.

A dollar invested in Treasury bonds in 1900 would have generated a capital of $293 by 2017, far away from the $47.661 made by investing in the stocks of large corporations, but also distant from the only $29 obtained in the Treasury bills.

In purchasing power terms, this dollar would have resulted in $10.2 by 2017, versus the $1.654 of the stocks investment, but far superior to the slim $2.6 provided by the Treasury bills.

Having to wait 117 years in time deposits and savings accounts that, at best, will allow little more than doubling the capital has no logic when there are other low risk options with much better returns as government bonds.

Thus, investment in Treasury bonds has a much lower return than the one in stocks of large companies but is clearly superior to the inflation rate and time deposits and savings accounts rates.

This means deposits and savings accounts should only be made for the monies we need in the day-to-day, to live the short term and to meet financial needs up to 1 year.

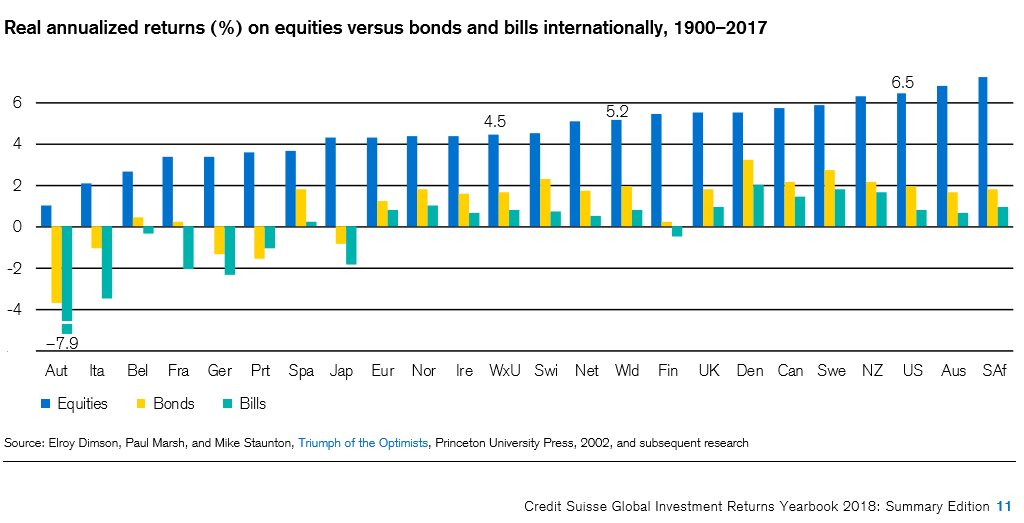

The following chart shows the difference in average annual return rates between stocks of large companies and those of Treasury bonds and Treasury bills for several countries in the same period from 1900 to 2017:

The situation is similar to the case of the US, but reveals some interesting differences.

Differences in average annual rates of return are positive in most countries, but there are some countries in which they were negative.

These are mainly those countries which were involved in major wars or weak and indebted economies, in which there were pardons or sovereign debt restructurings and or periods of hyperinflation.

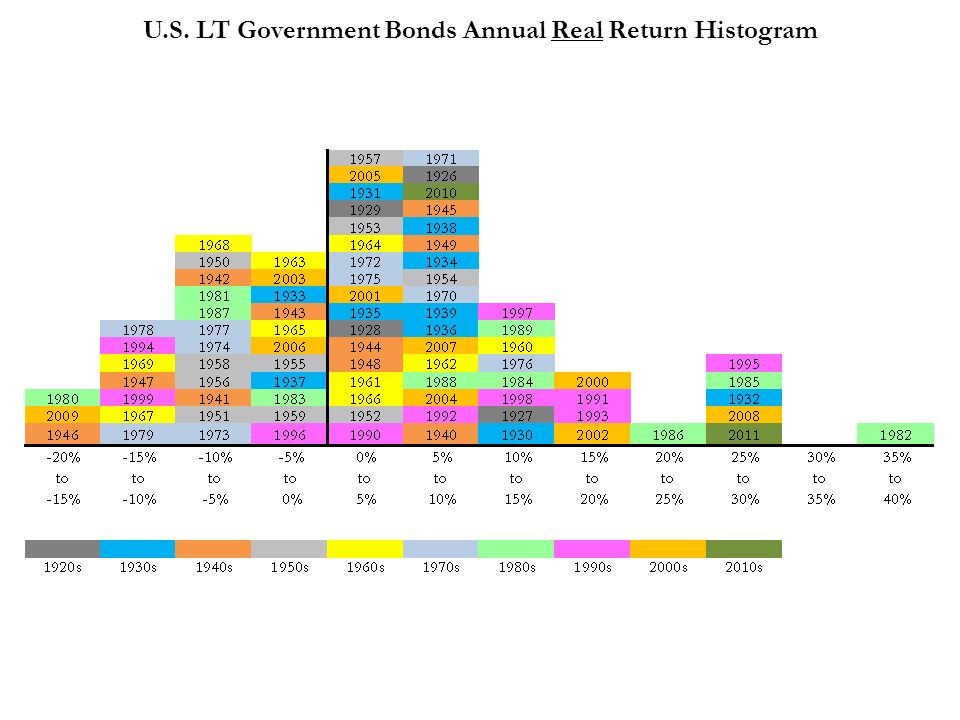

The following graphic shows the distribution of the real average annual rates of return of US 10-year government bonds between 1926 and 2011:

In more than 2/3 of the years, the 10-year Treasury bond provided positive real returns. However, years that these rates were something negative, with losses exceeding 10%, were usually associated with periods of high inflation.

We can also see that higher real rates of return, exceeding 10%, were observed since the 1980, in the last 30 years, known as the strongly advantageous period for bonds (“bonds long bull market”).

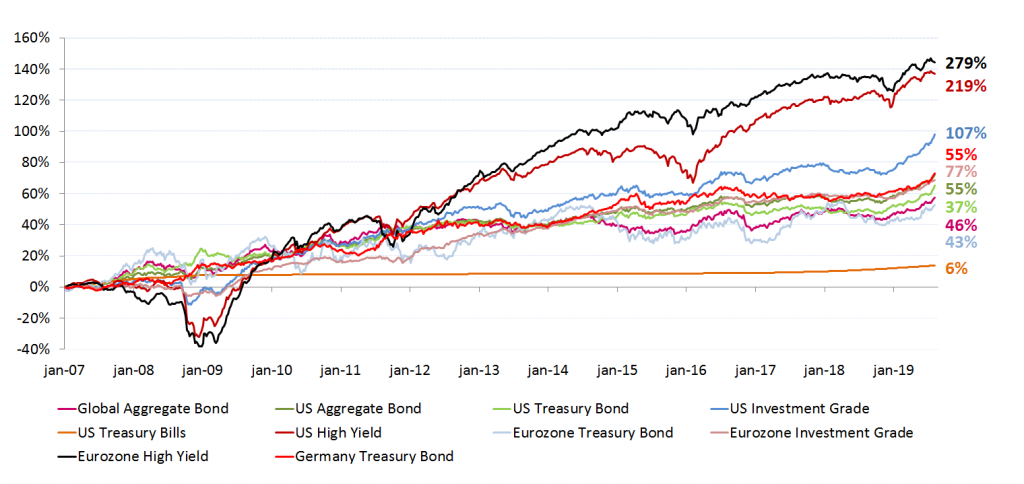

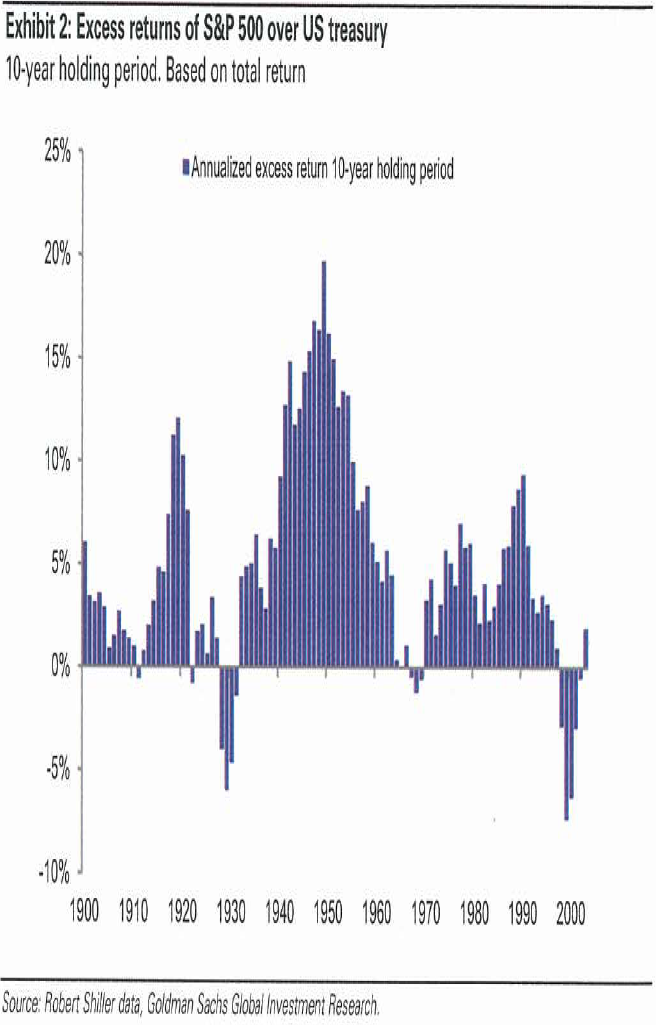

The following graph shows the difference of the annualized rates of return for periods of 10 years of investment in stocks of large companies and Government bonds to the U.S. between 1900 and 2014:

There are few years in which the annual rates of return on investments for periods of 10 years in bonds outperformed those in stocks of major companies: more precisely are 14 out of 114 years.

They have occurred mainly in two periods of financial crises, the great depression and the conjunction of the technological bubble with the great financial crisis.

#2: Because bonds are low risk and far less risky than stocks

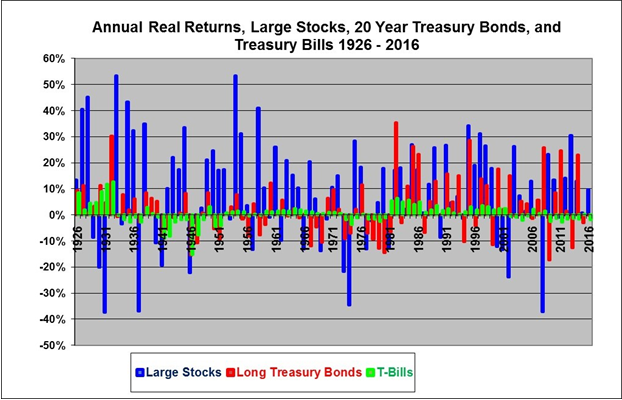

The following graph shows the annual real returns of investing in stocks of large companies, 20-year Treasury bond and 3-months Treasury bills, for the US, between 1926 and 2016:

We see that the real returns on large stocks, represented by the blue line, are much higher than those of the other assets on average, but also exhibit greater variability or fluctuation.

During these 90 years, we had about 30 years with negative real returns of stocks, 7 years in which these were superior to -20% (it is also true that there were more years with positive returns that exceeded the +20%).

Real returns of Treasury bonds fluctuated much less and there wasn’t any year that reached the -20% level (Treasury bills have lower volatility, but a substantially lower average real return).

It is this variability or fluctuation of returns that is known as volatility or risk (especially in its negative manifestations) of investments.

The risk of investing in bonds is quite smaller than in stocks (the greater returns correspond to higher risk and vice versa: there’s no free lunch in finance).

Increasing the term of investments or investment period reduces the risk, both for stocks or bonds but more for the former

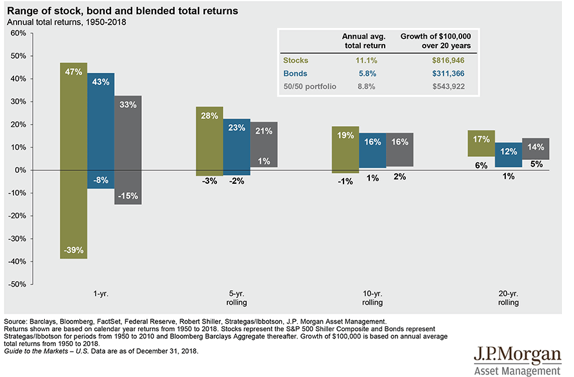

The following chart of shows the maximum and minimum values of the annualised returns for investment periods of 1, 5, 10 and 20 years, for large stocks and 10-year government bonds in the United States, between 1950 and 2018:

If the maximum value of negative investment returns to 1 year investment period is very unfavourable for stocks compared with bonds, for 5 years and 10 it is practically equivalent and for 20 years the situation is the opposite.

As market fluctuations are essentially short-term, in which corrections are followed by recoveries, increasing investment periods dilutes these fluctuations.

The fluctuation bands for both assets are narrower and the investment in large stocks is the most favourable for investment periods equal to or greater than 5 years.

This information shows that if we have an investment horizon of 20 years or more we should invest 100% of our wealth in large stocks as not only our average annual return will be superior but the risk is also more favourable. We might even say the same for investment horizons of only 10 years.

#3: Because we have deposits and savings in excess that do not yield anything material, that would have better returns with small risk if they were invested in bonds

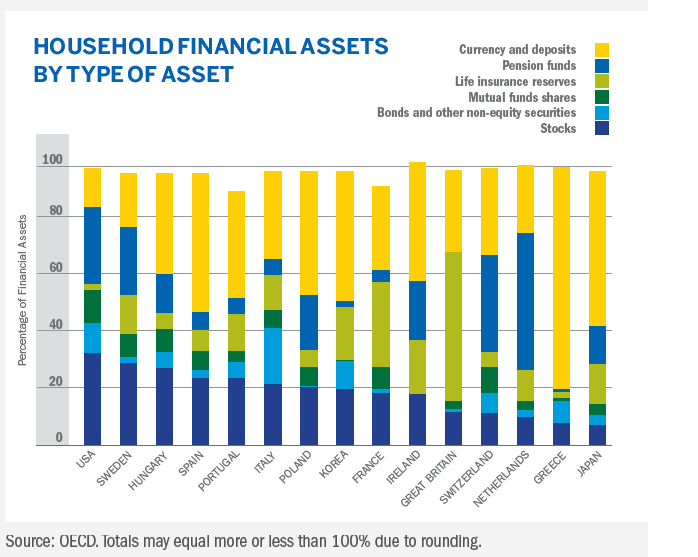

The following graph shows the breakdown of the household financial assets of in many OECD countries:

There is an excessive bias for currency and deposits in many countries such as Portugal, France, Ireland, Greece, Japan (which should be related to the financial crisis of the 1990’s) and Eastern Europe, with percentages of more than 40%. In countries such as the USA, Sweden, Italy, Switzerland and the Netherlands, investments in stocks and bonds, direct and via pension funds, mutual funds or life insurance reserves, exceed 60%.

Part of the explanation may be that some of the former countries are less wealthy, so most families only have money to live day by day.

Another would be that these countries have lower financial literacy, or that their non-financial assets, such as housing, are a most important slice of the household net worth.

However, there are several studies which indicate that not only these, but in all countries, households tend to have more money in currency and deposits than they need, either for convenience or indulgence.

We saw previously that returns on these savings are very low. This is one of those situations where adverse behaviours remain due to lack of right incentives, since the opportunity cost is invisible (families don’t realize the money they are losing for failing to win or letting it go).

#4: Because diversification of investments between stocks and bonds allows us to balance returns and risk, and to adjust them to our personal profile

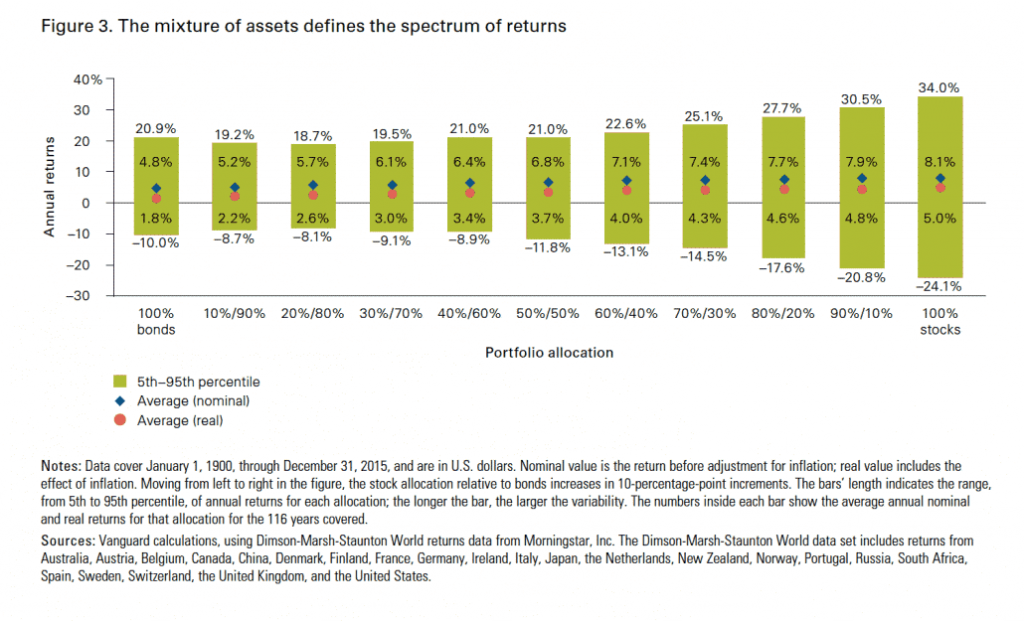

The following graph shows the average annual returns, in nominal and real terms (inflation deducted), as well as returns for the best and worst 5% cases obtained by combinations in different proportions of investments in large stocks and 10-year government bonds, between 1900 and 2015:

If we invest all in bonds we would have 4.8% average returns and 1.8%, in nominal and real terms, respectively. The annual return was -10% in 5% of the worst years of + 20.9% in the 5% best years.

Investing everything in large stocks would have had average returns of 8.1% and 5.0%, in nominal and real terms, respectively. In 5% of the best years that return was of + 34%, and in 5% of the worst years, was -24.1%.

The 50/50 mix would have resulted in average returns of 6.8% and 3.7%, in nominal and real terms, respectively. The values of the 5% worst and 5% best years would be -11.8% and + 22.6%, respectively.

We conclude that bonds are interesting for conservative people or for situations with a priority on the preservation of assets.

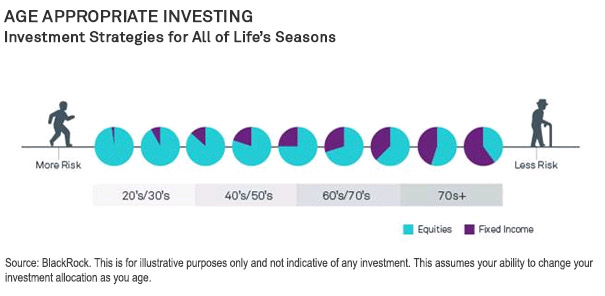

As the increase of the investment period reduces the risk, asset management professionals use rules for diversification of investments depending on the age of the investor

Having previously seen that the increase of the investment period mitigates the risk for both assets, but more importantly for stocks, it is not surprising that there is a generic rule or recommendation of investment allocation in line with the age of the investor.

The following graph prepared by Blackrock, one of the largest world asset managers, highlights this rule age-based allocation:

On the beginning of our active life almost all the assets should be invested in stocks to benefit from the potential of its appreciation for as long as possible.

From 40 or 50 years of age, we must begin to allocate part of the investment to bonds.

From 70 years old onwards, most of the assets must be invested in bonds.

The same professionals also use similar rules on the basis of the date fixed for the investment goal, in particular, for retirement

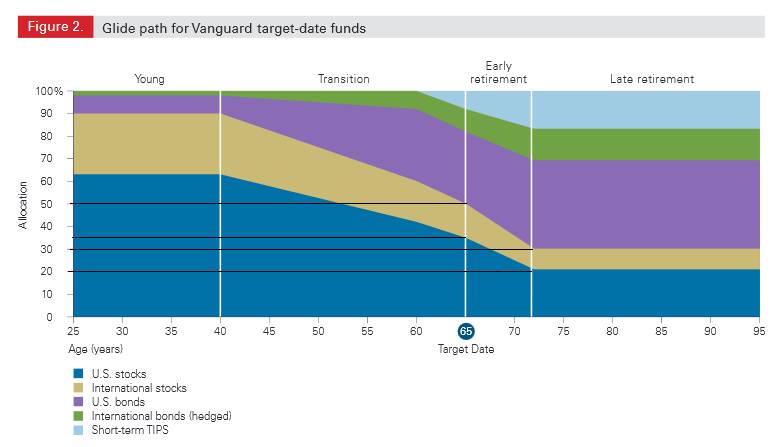

The following graph shows the allocation made by Vanguard, one of the world largest asset managers, in its target-dated funds to the retirement at 65 years of age:

From 25 to 40 years old, bonds represent only 10%, increasing gradually from there until the age of 60 years to around 40%.

This allocation increases to 50% at retirement age and reaches the maximum of 70% from 72 years, stabilizing, from then on.

Bonds are useful from middle age onwards, when we have less than 10 or 20 years that we can’t run the risk of major wealth losses, or for situations or moments of instability of our personal lives when we can’t risk financial losses (disease or unemployment), in order to ensure our financial commitments.

#5: Because we need the stability of the income of the bonds, and above all its mitigating effect of the risk of investments in stocks

The bonds have the advantage of providing a regular income and stability to our investments.

In addition, and perhaps their biggest advantage, is serving to mitigate the investment risk in stocks.

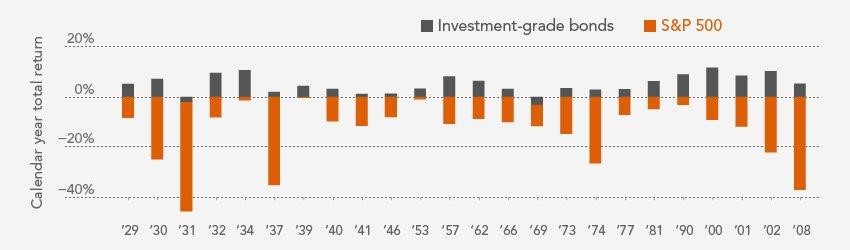

The following graph shows the annual returns on investments in large stocks and investment-grade bonds investment, for the United States, for the years between 1929 and 2008 that registered losses in stocks:

Source: Fidelity Capital Markets, Investment Themes 2017

In almost all of these 24 years (in a total of 80 years) of losses in the stocks, there were gains in the bonds. The exceptions were the years of 1931 and 1969, albeit with negligible values.

Bonds act as an excellent diversification component to accompany the investment inn stocks, which have a higher capacity of appreciation.

This complementarity is certainly their greatest advantage, especially in times of stress or stock market crises.

Bonds are like protective umbrellas, especially in times of severe crisis in the markets.

They offer stability.

Another advantage is that they are reasonably safe and with more interesting returns than deposits and savings accounts.

The biggest advantage is the effect of their complementarity with stocks. They act and provide a safeguard, an insurance policy or a cushioning pad when combined with stocks (without cost, but with income). They are the cane for life and for investment in stocks.