Reason and logic are the most important decision factors to compel us to do something. We only do what makes sense to us and with a purpose. Only after comes the how, how much, in what, when and where. There are 5 great reasons to invest in the stocks of the biggest companies in the world.

#1: Because stocks are the financial asset with the highest returns in the medium and long term and the only one that affords significant asset appreciation in real terms

#2: Because in the medium and long term the risk of investing in stocks is much mitigated

#3: Because we have medium-and long-term goals that are not achieved otherwise (with bonds, and even less with deposits and savings accounts)

#4: Because diversification of investments between stocks and bonds allows us to balance the return and risk, and adjust them to our personal profile

#5: Because we cannot ignore the wealth creation coming from the returns and capital appreciation of the investment in stocks

#1: Because stocks are the financial asset with the highest returns in the medium and long term and the only one that affords significant asset appreciation in real terms

Stocks are the financial asset with greater returns in the medium and long term.

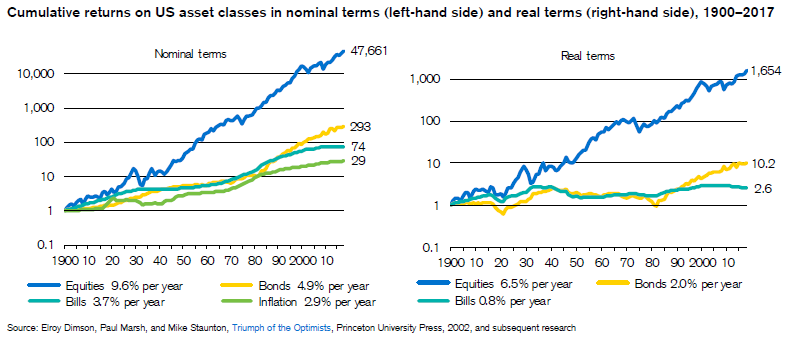

The following graph shows the cumulative returns of 2 major financial asset classes in the U.S. of 1900 to 2017:

The stocks of large companies, measured by the S&P 500 index, had an average annual return of 9.6%.

The average annual return of the 10-year Treasury bond was only 4.9 percent, still well above the average annual return of 3.7% of 3-month Treasury bills (the main short-term investment of commercial banks, and as such, the ceiling interest rate reference they pay for deposits), and average annual inflation rate of 2.9%.

A dollar invested in 1900 would have generated in 2017, after 117 years, $47.661 if invested in stocks of large companies. The same dollar would result in a $293 capital if invested in Treasury bonds and $74 if invested in Treasury bills.

Due to inflation, a dollar in 1900 would have the same purchasing power than $29 in 2017. To get the value of the previous capital, in real terms, we would have to divide the values by the inflated dollar.

The value of the capital invested in stocks of large companies increased 162 times more than the one invested in Treasury bonds. In real terms, the accumulated capital would be $1.654 in shares of large companies.

The accumulated capital in real terms would be $9.9 in bonds and just $2.6 in Treasury bills (it is proof that deposits and savings accounts don’t yield enough, even in the very long term).

Expect 117 years, for what? – may someone ask.

Although 117 years may be a purpose in life, such as the transmission of a heritage in inheritance, we can see from the chart that this stock appreciation happens gradually, and for long periods, briefly interrupted by falls in some years.

Therefore, it is not necessary to wait that long. It is an evolution along almost a straight line with some occasional breaks, called market corrections.

As we shall see below, it is precisely to mitigate the risk of these market fluctuations and capture all their potential gains, that one should recommend investment in stocks for timeframes from two to three years.

The next years will be different and worse than the past – others say! We live the present and the recent past so intensely that we tend to think that the problems and risks happen only now.

If we remember that in these 117 years are included two great world wars, two major financial crises (great depression and great financial crisis), periods of hyper-unemployment and hyperinflation, several monetary crises, multiple bankruptcies of States and companies, etc., nothing could sound more fake. History repeats itself: with progress and crises.

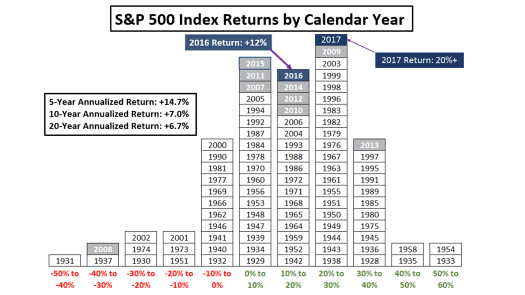

The following graph shows the distribution of the annual rates of returns of the stocks of large US companies, given by S&P 500 its main market index, between 1928 and 2017:

You can easily see that this excess of the annual average rate of return was positive in more than 2/3 of the years. This rates difference was more negative in the years of the great depression, the great financial crisis, and the technology bubble.

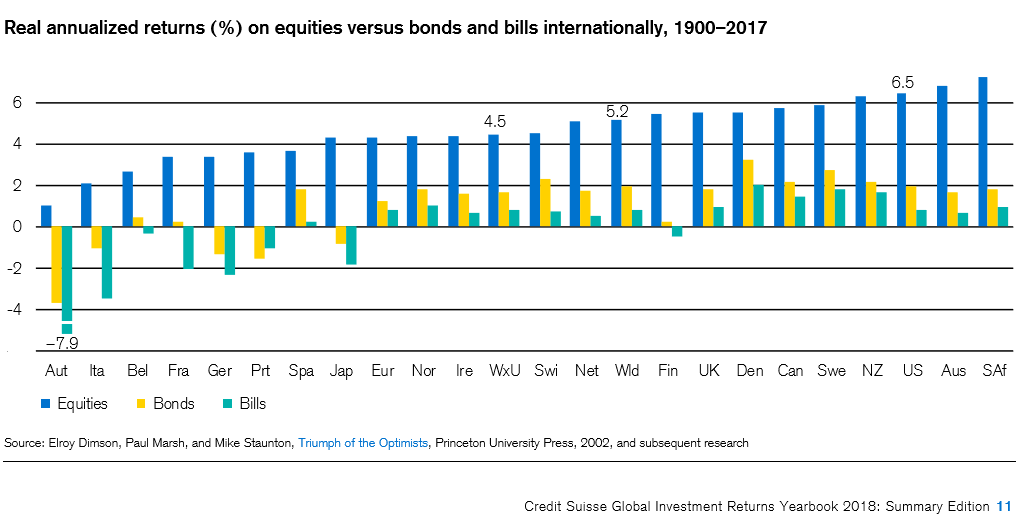

The U.S. case is not unique. The chart below shows the average annual return rates of major stocks indexes and government bonds, in real terms (inflation deducted), registered in several countries of the world, between 1900 and 2017:

The average annual rate of return of the stocks of large companies worldwide was 5.2%, less than that of 6.5% in the US. This was more than double the rate of Treasury bonds and incomparably greater than 0.5% of Treasury bills.

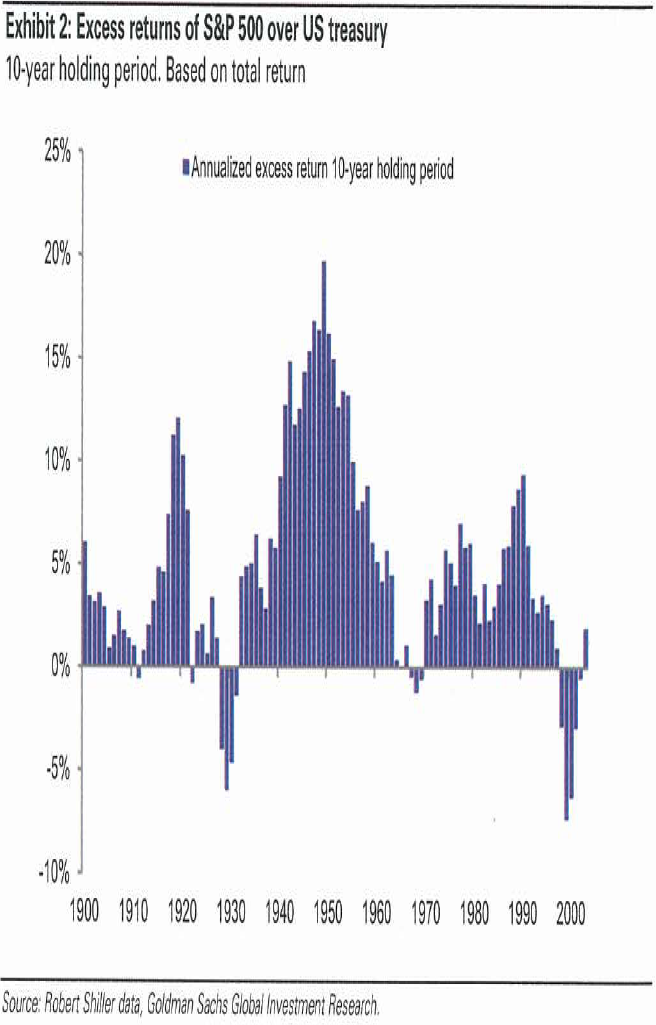

Another useful way to evaluate the returns between stocks and bonds is to compare their values for periods longer than a year but, for example, for 10 year periods:

This comparison is useful because many of our financial goals have a timeframe of not less than 10 years.

As we can see rare are the occasions when the annual average rates of return for periods of 10 years of the stocks of large companies were lower than government bonds. This situation occurred in just 12 of the 113 total cases, centred in periods of financial crises in the late 30s, and the 2000 years.

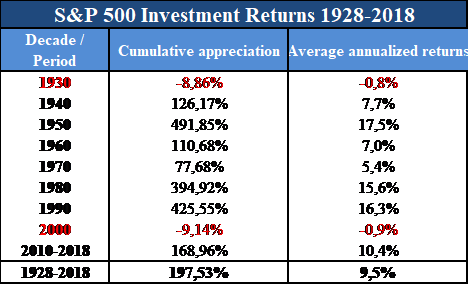

The following table shows the average annual return rates for decades in the U.S., from 1930 to date:

.

The S&P 500 average annual rates of return were negative, and very slightly negative, only in the 1930 and 2000. The average annual rate of return in this period was 9.5% per year.

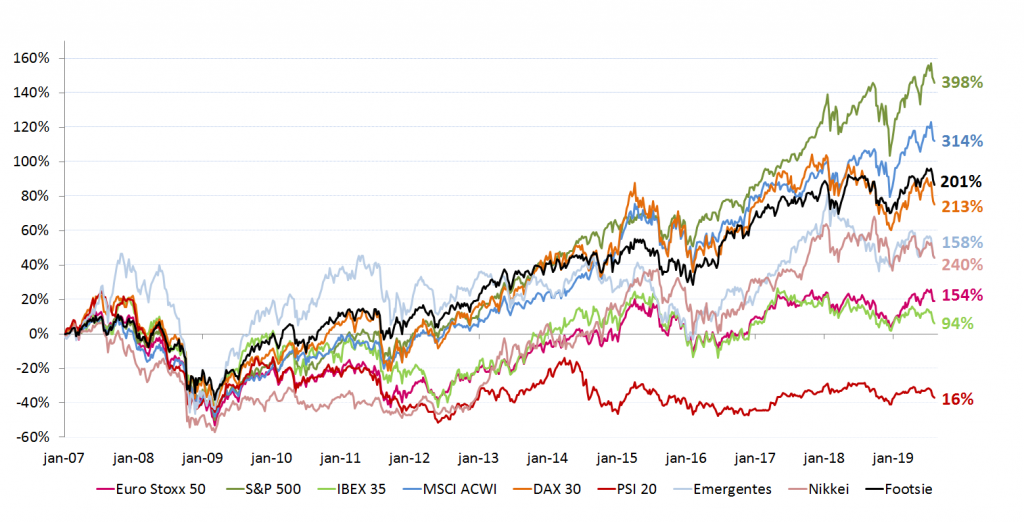

The following graph shows the evolution of the main stock market indexes from 2007 to date:

The great financial crisis of 2007-08, started by the subprime in the US, brought down all major indexes stock market indexes between 40% and 60%, due to the contagion of globalization of markets.

In late 2008 and early 2009, all the main indexes began to recover, but two distinct realities.

The American, German and World indexes surpassed the pre-crisis levels, registering accumulated valuations in excess of 200% and even 300% from the March 2009 lows.

The remaining European indices, in particular the Euro zone (Eurostoxx 50), French (CAC40) and the Spanish (IBEX35 index), have not yet reached the pre-crisis levels, due to the great European sovereign debt crisis of 2011-12.

The Portuguese index (PSI20 was), not even exceeded the minimum levels of the pre-crisis of 2009.

#2: Because in the medium and long term the risk of investing in stocks is much mitigated

The stocks have higher returns, but have also more risk than bonds. There is no free lunch in finance!

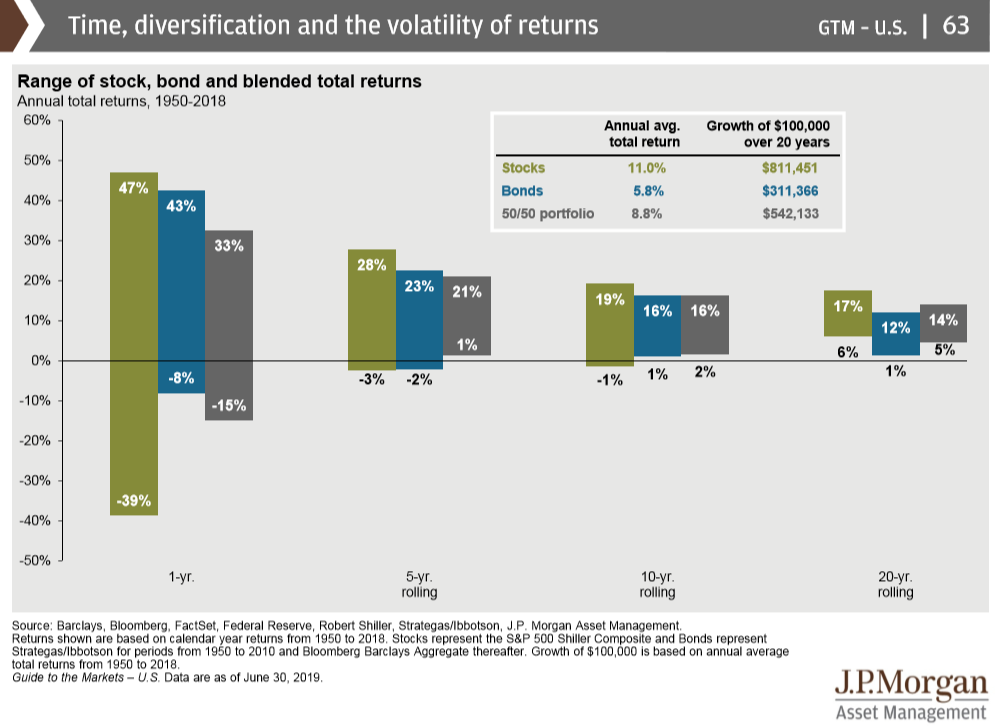

The following graph shows the rates of return and risk of both assets, in the U.S. since 1950 to date:

The stocks of large corporations had annual average rates of return of 11%, almost double the 5.8 percent of the Treasury bonds.

However, stocks had much stronger price swings than bonds. During this period, there were years in which the stocks lost 39%, while the bonds did not lose more than 8% on their worst year.

However, this situation changes radically when we look at the rates of return on both assets for a period longer than 5 years. Stocks lost a maximum of 3% a year in 5-year periods, very close to 2% per year of bonds. In 10 and 20-year periods, stocks are even more interesting.

More important than the ranges of fluctuation is the frequency or probability of occurrence.

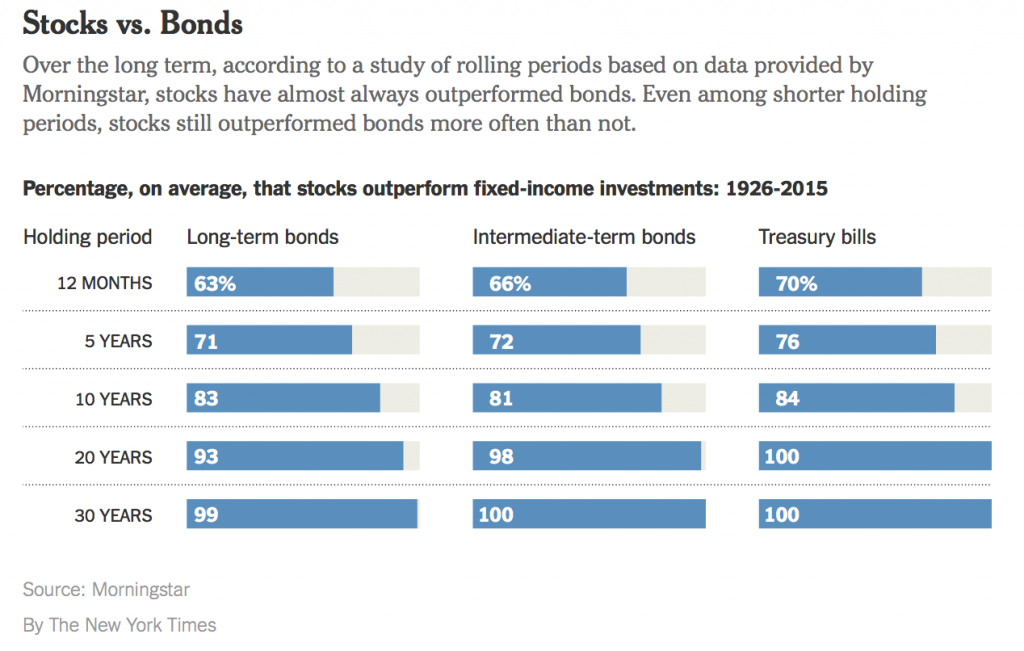

The following graph shows the percentage of periods in which the rates of return of the stocks of large companies have beaten the Government bonds and Treasury bills, in the intermediate term (5 years) and long term (more than 10 years), in the period from 1926 to 2015:

In 63% of the years the stocks rates of return have exceeded the long-term bonds. These percentages rise to 71% in periods of 5 years, 83% in 10 years, 93% in 20 years and 99% in 30 years.

That’s why we say that stocks are unbeatable in the medium and long term. Increasing the timeframe of investments reduces the risk, both for stocks or bonds but more for the former.

#3: Because we have medium-and long-term goals that are not achieved otherwise (with bonds, and even less with deposits and savings accounts)

What are our key financial goals?

The answer to this question is fundamental because the goals, such as needs, interests or aspirations, are the reason and motivation we don’t spend, save and invest for the future.

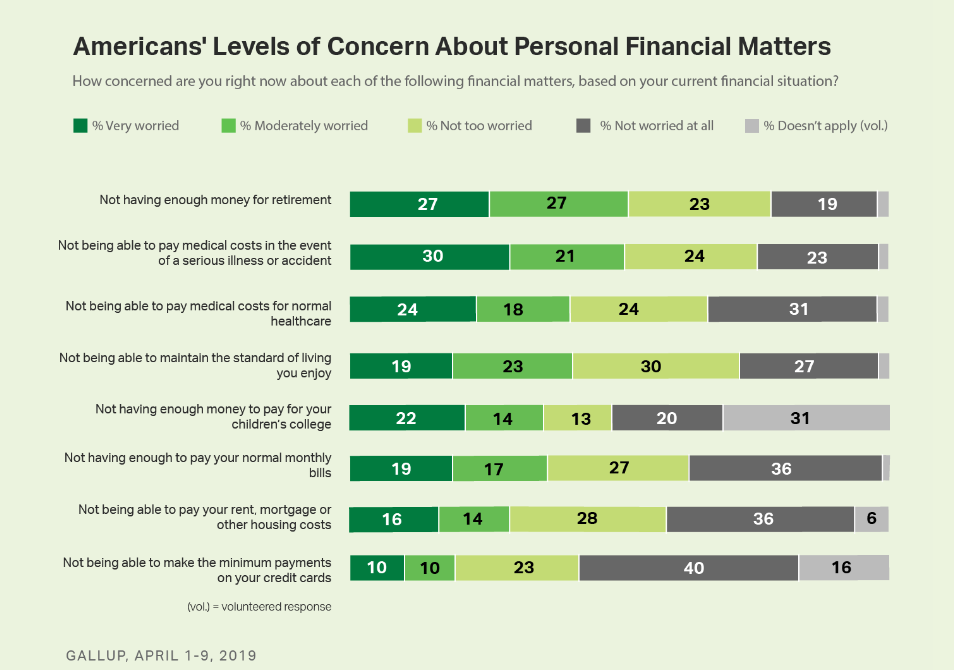

Gallup conducts an annual survey in the U.S. on the major financial concerns of respondents, and the most recent shown the following results:

We see that at the top of the priorities of concerns arise goals that are divided between the long term, such as the retirement, being able to maintain the standard of living, pay for children’s college, and the medium term, such as, have funds to meet emergencies or unexpected accidents, illness or health care.

These end up having more importance than others which are clearly of short term, like paying monthly bills, paying rent, mortgage or credit cards.

What we can conclude is that we have our everyday life reasonably controlled, but not what it goes beyond that, and that’s what concerns us. So, these should be the primary financial investment goals.

However, often we have most of our wealth held in cash or liquid assets, which yield little or almost nothing, and we invest a small piece of it in financial assets, with much higher returns.

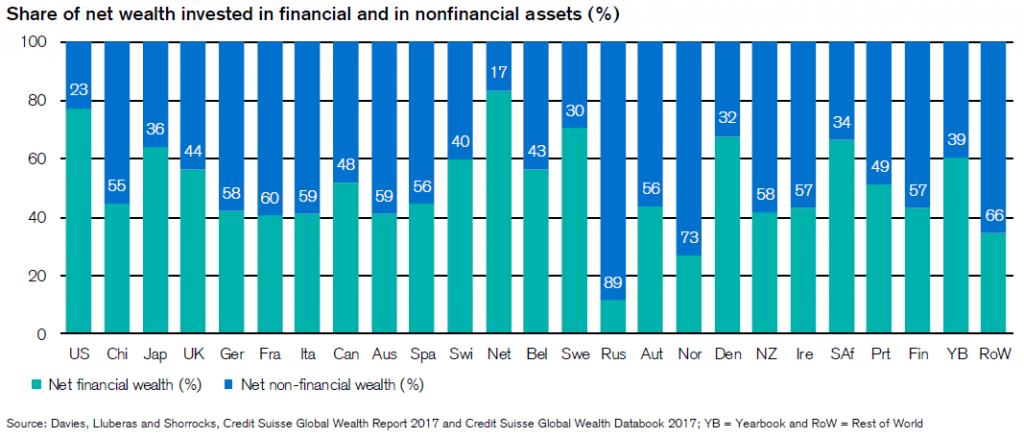

In most countries household wealth is invested in non-financial assets, especially in housing. This investment does not yield!

Investment in financial assets only prevails in countries such as the USA, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark and South Africa. In Portugal, wealth is distributed equally between financial and non-financial assets.

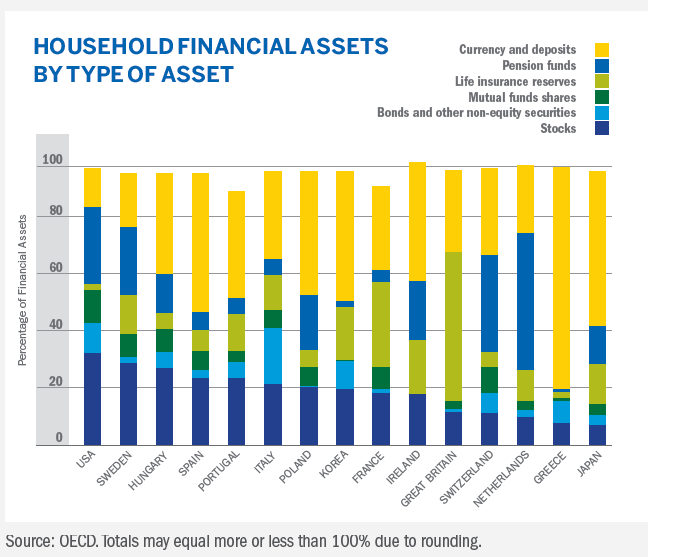

The following graph shows the composition of the financial assets of households in several countries:

Cash and deposits predominate in Portugal, Spain, Ireland, Greece, Japan and some countries of Eastern Europe. Financial assets such as stocks and bonds, held directly or through investment funds, pension plans or insurance futures, have a large weight in the US, Sweden, Italy, Switzerland and the Netherlands.

#4 savings: Because diversification of investments between stocks and bonds allows us to balance the return and risk, and adjust them to our personal profile

Diversification with stocks and bonds allows us to fine tune the levels of return and risk adjusted to our situation and financial goals

Diversification by asset classes is made by combining investments in stocks and bonds, determining the levels of return and risk that we want, and enable us to optimize and improve the efficiency of the investment portfolio.

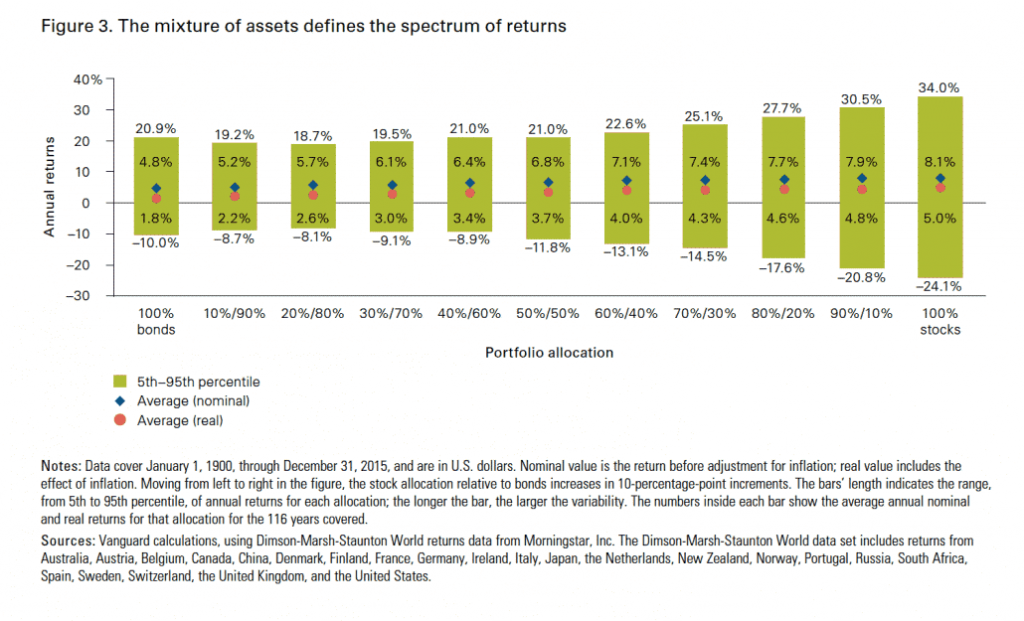

The following graph shows the average annual nominal and real (inflation deducted) rates of return and risk (assessed by 5% worst and best annual outcomes) provided by different combinations of investments in stocks and bonds during the period 1926 to 2015:

If 100% was invested in Treasury bonds, the average real annual return had been 1.8% and the result ranged from -10% and + 20.9%. In the opposite cash of 100% investment in stocks of large companies, the average real annual rate of return was 5% and the yields ranged from-24.1% and + 34%. In the middle, the 50/50 in stocks and bonds, the average annual real rate of return was 3.7% and the intervals range between -11.8% and +21%.

Because time length improves the return/risk trade-off, we must take into account the term of the investments in the decision of the financial assets mix.

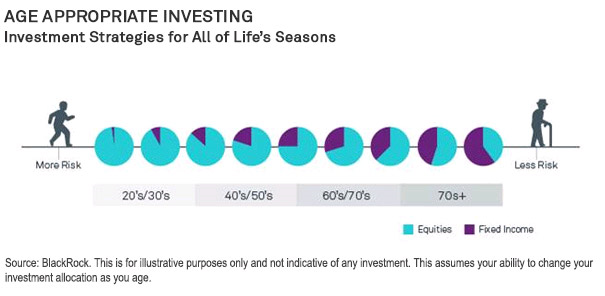

As the increase of the investment period reduces the risk, asset management professionals use rules for diversification of investments that depend on the age of the investor

A commonly used rule followed by individuals and professionals of wealth management, is one that links the investor’s age to his asset allocation.

The following graph shows the rule recommended by Blackrock, one of the largest asset managers in the world, to people from the 20 to the more than 70 years of age:

At the beginning of our active life we have a very long time ahead of us, and we should have an allocation almost entirely made up of stocks of large companies.

As we get old, we should moderate this allocation, introducing a bond component with increasing relevance.

When we reach the age of 70 years old, the largest allocation should be made in bonds.

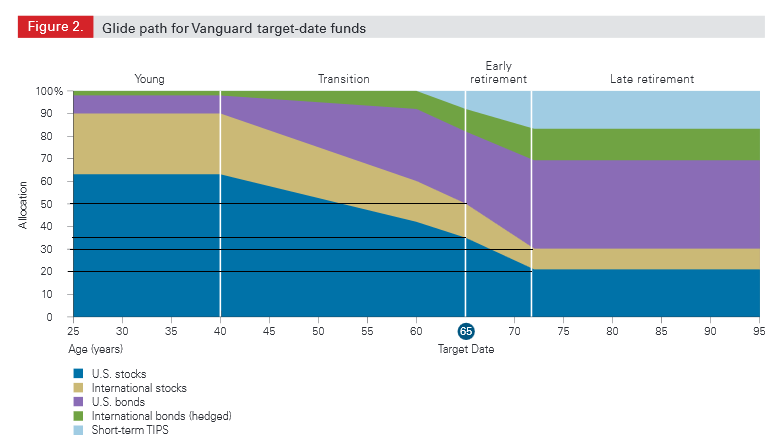

The same professionals also use similar rules on the basis of the date targeted for the purpose of investment, in particular, to retirement date

The following graph shows how the Vanguard, one of the largest asset managers in the world, makes stocks and obligations allocations for the particular case of their retirement target portfolios that have 65 years old as the official date:

Between 20 and 40 years of age, we should invest 90% of our retirement fund in stocks, leaving only 10% for bonds.

From 40 years up to 60 we are decreasing gradually the allocation of stocks to 60%, and then up to 70 years of age, more sharply to the 30%, in order to mitigate the risk of stocks when the accumulated capital should be to your peak.

From that age onwards the allocation should stabilize at that level.

#5: Because we cannot ignore the wealth growth coming from the returns and capital appreciation of the investment in stocks

As we saw previously, stocks are the only asset that provides a strong wealth building in the medium and long term.

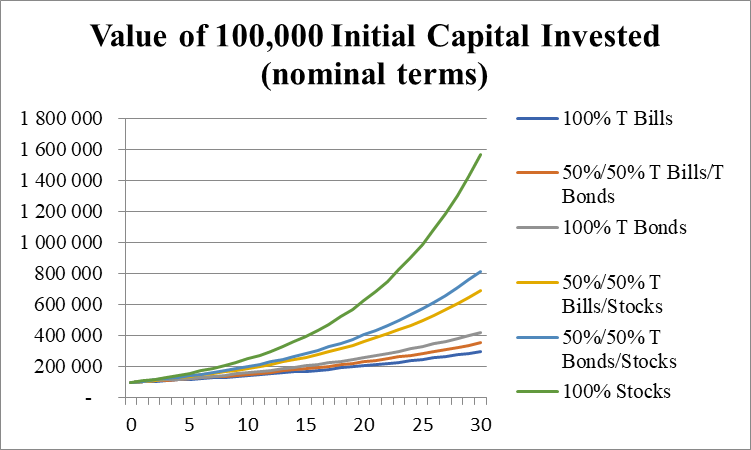

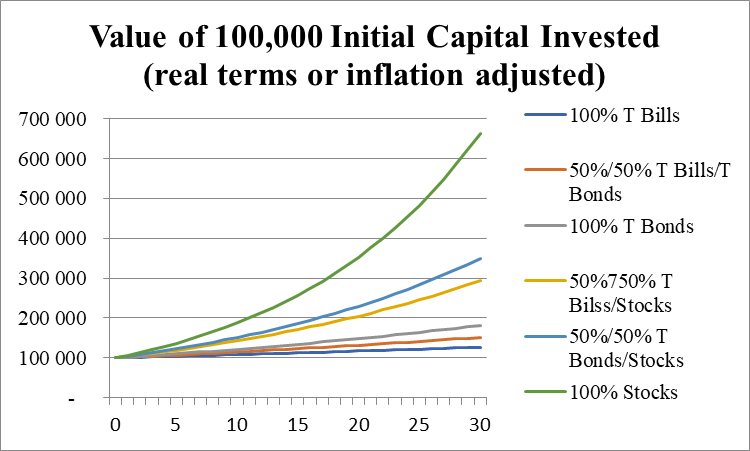

The following graph shows the accumulated capital, in nominal and real terms, resulting from an investment of 100.000 in different proportions of stocks and bonds for a period of 50 years, with reference to the historical rates of return (9.6% and 4.9% in nominal terms, and 6.5% and 2.0% in real terms):

The investment of a capital of 100,000 at historically assets rates of return would result in capital of 297,000, 420,000 and 1,564,000 if invested in Treasury bills (returns equivalent to deposits), 10-year Treasury bonds or stocks of large U.S. companies, respectively. We see that even a mix of 50/50 Treasury bills and stocks results in a capital of 690,000 that is much higher than the one of 100% in bonds. The 50/50 mix of bonds and shares results in a capital of 816,000, double the investment in bonds alone.

In real terms or adjusted for inflation, that same investment of a capital of 100,000 at historically assets rates of return would result in capital of 127,000, 181,000 and 661,000 if invested in Treasury bills (returns equivalent to deposits), 10-year Treasury bonds or stocks of large American companies, respectively.

We see that even a mix of 50/50 Treasury bills and stocks results in a capital of 293,000, which is almost double that of 100% in bonds. The 50/50 mix of bonds and shares results in a capital of 348,000.

Stocks are clearly the financial asset with the highest returns and the only one that provides significant wealth growth in real terms.

Their main advantage is the ability and the potential for wealth building, which allows us to achieve more financial goals.

They are very useful when we have investment time horizons over 2 or 3 years, becoming unbeatable in horizons more than 10 or 20 years, through the mitigation of risk by time.

They are the energy, youth and vitality of our financial net worth.

They must accompany us all life long, almost 100% at the beginning, and 30% in old age.

To ignore the investment in stocks is to waste a significant part of our financial life, as not investing in more profitable terms must also be seen as a loss.