What is the importance of each of the biases in general and for each generation?

Theory and practice show that as investors we are subject to behavioural bias that undermine the performance of our investments and are very costly

Benjamin Graham, the father of value investing and mentor to investment manager Warren Buffet, already said that “the investor’s biggest problem – and even his worst enemy – is likely to be himself.”

A few years later, the parents of behavioural economics Kahneman, Tversky and Thaler proved that humans do not react to uncertainty by carefully and rationally examining the information available. Instead, real people use a series of mental shortcuts mixed with emotional reactions to make decisions.

These mental shortcuts influence and make mistakes in making several economic decisions, in the context of investment management.

Daniel Kahneman was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2002 and is the author of the book, Thinking Fast and Slow, and Richard Thaler was also awarded the Nobel Prize in 2017 and is the author of Nudge.

Recent studies indicate that this is the main factor of the negative deviation or loss of investor profitability in relation to the performance of the stock markets, having a weight of 40% and representing 1.50% in annual returns, and for an investment period as long as 20 years

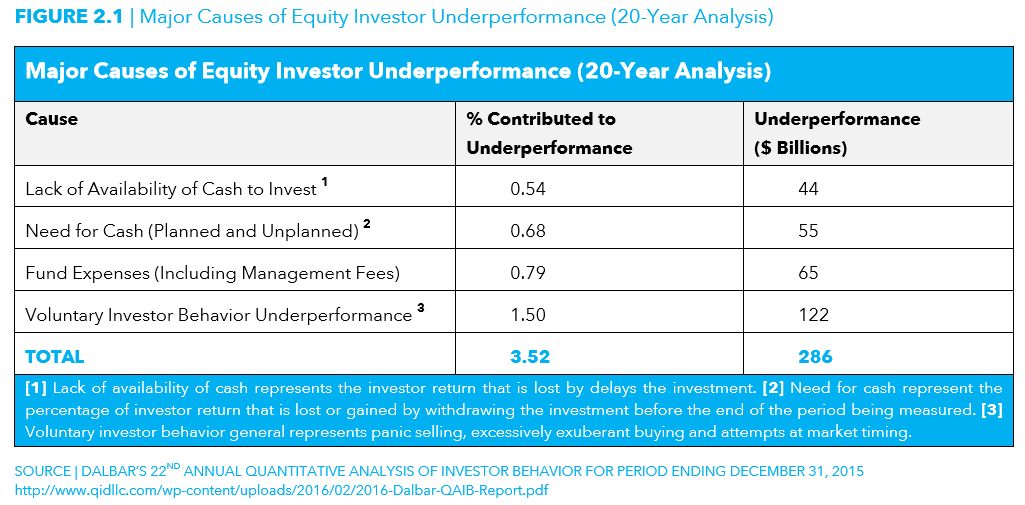

A 2016 study by Dalbar, which every year evaluates the performance of investments made by the average investor compared to that of the market, concluded that these biases are the main responsible for the poor performance of investments.

They cost 1.5% per year in terms of returns on investments in the stock markets, representing 40% of the total deviation of 3.52% per year of market returns, and prevail for periods of 20 years.

Its cost is almost twice the second highest cost, that of the expenses of the investment products chosen by the investor, the two losses most controllable by the investor.

The remaining two factors are planning errors, with less control by the investor, and include the lack of means to invest and the need for liquidity to meet unexpected expenses.

These voluntary investor behaviour errors usually consist of panicked selling, exaggerated optimism, and attempts to manage market timing.

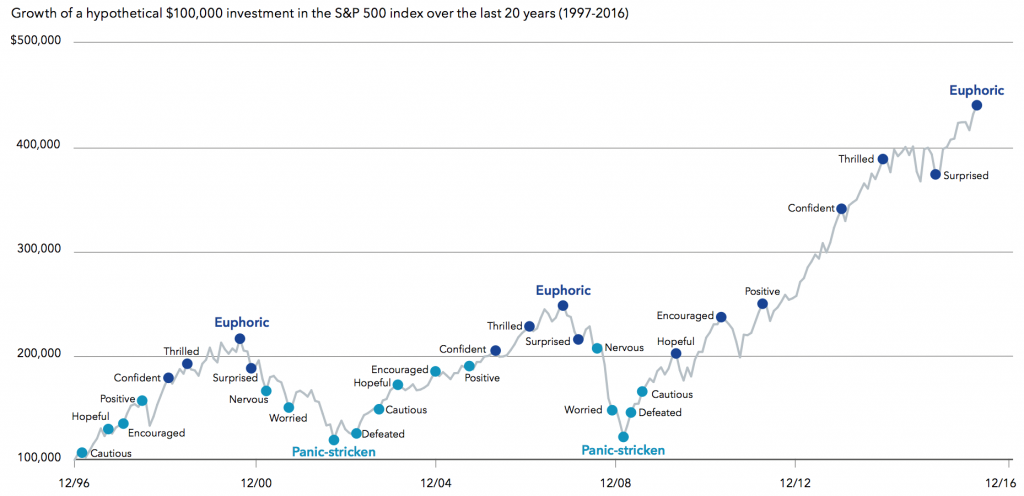

It is widespread opinion that as investors we experience moments of euphoria and panic throughout market cycles that hurt us, as the S&P 500’s evolution chart between 1996 and 2016 aims to portray:

Investors enter the market cycle cautiously and as investments increase in value, they become more encouraged, positive, confident, enthusiastic and invest more and more, until at peak they are euphoric and have taken too much risk.

When markets start to go down investors first get surprised, then nervous, worried, and often at the market bottom, they panic and sell much or all of their investments. In this way, they buy high and sell low, that is, they buy more expensive and sell cheaper, contrary to what would be smart to do.

Knowing and being aware of the main biases is essential for us to know how to manage and mitigate their negative effects on investment management

According to behavioural economics promoters, people are influenced by two primary behavioural prejudices, cognitive errors, and emotional biases.

Cognitive errors deal with the way people think and result from memory errors and information processing and are therefore the result of faulty reasoning.

There are two sets of cognitive errors, the belief perseverance biases and information-processing biases.

The belief perseverance biases include conservatism, confirmation, representativeness, illusion of control and hindsight.

The information-processing biases include anchoring and adjustment, mental accounting, framing, availability, self-attribution, outcome, and recency.

Emotional biases are the result of reasoning influenced by feelings. Emotional prejudices are based on feelings rather than facts and result in irrational decisions that usually happen in times of stress. Emotional prejudices include loss aversion, overconfidence, self-control, status quo, donation, regret aversion, and affinity.

Understanding and detecting prejudice is the first step in overcoming the effect of bias on financial decisions. By understanding behavioural biases, we may as investors be able to moderate or adapt to bias and, consequently, improve economic outcomes.

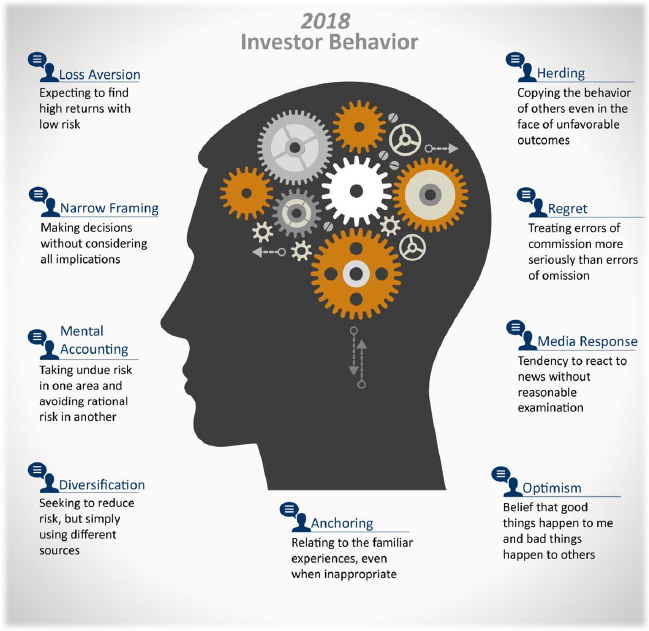

The main behavioural biases are as follows:

Loss aversion: We expect to find high yields with low risk

Herding: We copy the behaviour of others

Narrow framing: We make decisions without considering all the implications

Regret: We take mistakes to do more seriously than omission errors

Mental accounting: We take undue risks in one area and avoid rational risks in another

Media response: We tend to react to news without reasonable analysis

Naïve diversification: We try to reduce risk, but we simply use different sources

Anchoring: We attach ourselves to family experiences, even when it is appropriate

Overconfidence or optimism: We believe that good things happen to us, and bad things happen to others

In forthcoming posts, we will develop each of these biases.

What is the importance of each of the biases in general and for each generation?

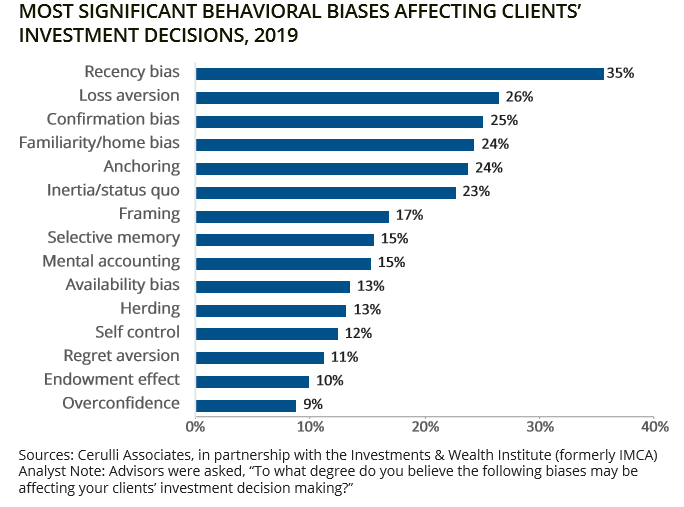

Charles Schwab, one of the largest and most reputable US brokers, sponsored a 2019 study on the main behavioural biases that affect investors in the opinion of its financial advisors, and came to the following conclusions:

Source: The role of behavioral finance in advising clients, Charles Schwab, 2019

The main bias, with 35%, is the current or recent memory that overlaps and makes us lose sight of history and past experiences. Next and almost on par, with between 23% and 26%, is the loss aversion, confirmation (we feel that what happens to us confirms our ideas), familiarity (we only invest in what is familiar to us), anchoring (we are stuck with certain values, ideas or reasoning) and the status quo (we have a lot of inertia, which makes us not change).

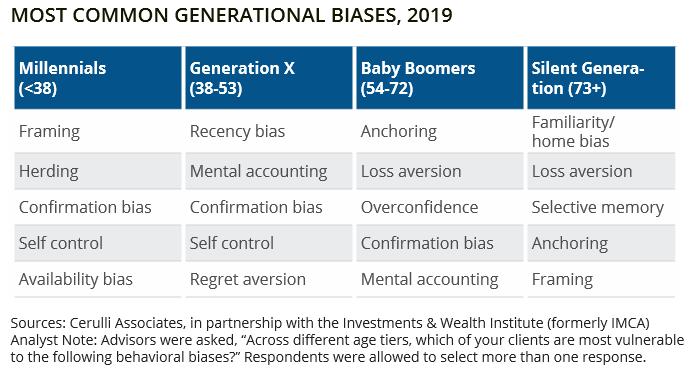

This study also evaluated the main prejudices for each generation, revealing some differences:

Source: The role of behavioral finance in advising clients, Charles Schwab, 2019

Confirmation bias arises in all generations except the older, Silent generation, over 73 years old. Self-control prevails in younger generations, Millennials and Gen-X, while loss aversion and anchoring arise more in older ones, Baby-Boomers and Silent, which is understood by the life cycle (irreverence and more caution and experience).

https://www.streamfinancial.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/real-investment-advice.pdf

https://wealthwatchadvisors.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/QAIB_PremiumEdition2020_WWA.pdf

https://www.schwabassetmanagement.com/resource/addressing-surge-client-behavioral-biases

https://www.franklintempleton.com/forms-literature/download/BF-B