From the decision to allocate to asset sub-classes to the decision on selecting the investment products

The diversification rationale (reminder)

Individual investors lose a third or more of the returns given by the financial markets

Only between 10% and 20% of institutional investors achieve the financial markets returns and it is almost impossible to know in advance who will be successful

However, despite all these studies, this reality is hard to accept for some investors because beating the markets seems so simple…thought if there were many would be rich

It is not easy to choose the best stocks than the market in general because the market odds do not help

Jim Collins’ reputed studies show that we only know how to distinguish the best companies “a posteriori”

Diversification in investments improves the risk/returns trade-off and it requires an investment in 30 or more securities

The diversification rationale (reminder)

Diversification is the most important and fundamental rule of wealth and asset management, and investments.

Diversification is a logical and rational attitude:

- Do not put all the eggs in the same basket;

- We don’t always hit the choices (in fact we fail so many or more times);

- The concentration on one or few investments develops our worst enemy in investments, our own ego: when we win, we double; when we lose, we stop investing; when we draw or even, we forget the opportunity cost;

- It is impossible to predict the performance of investments even in the short term (otherwise we would be rich);

- We want appreciation, but also preservation in investments, especially in times of “stress” of the markets;

- Combining investments, as well as asset classes, improves the return/risk trade-off of investments.

Harry Markowitz, Nobel Prize in Economics and father of financial theory of investments and wealth management, dubbed the diversification of the only free lunch in Finance.

Individual investors lose a third or more of the returns given by the financial markets

The response of most investors depends, as many consider that they can make better choices than the market in general, manage to beat the market and overcome the valuations of major market indexes.

In addition, they consider that the choice of securities is the most important success factor for the result of the investment.

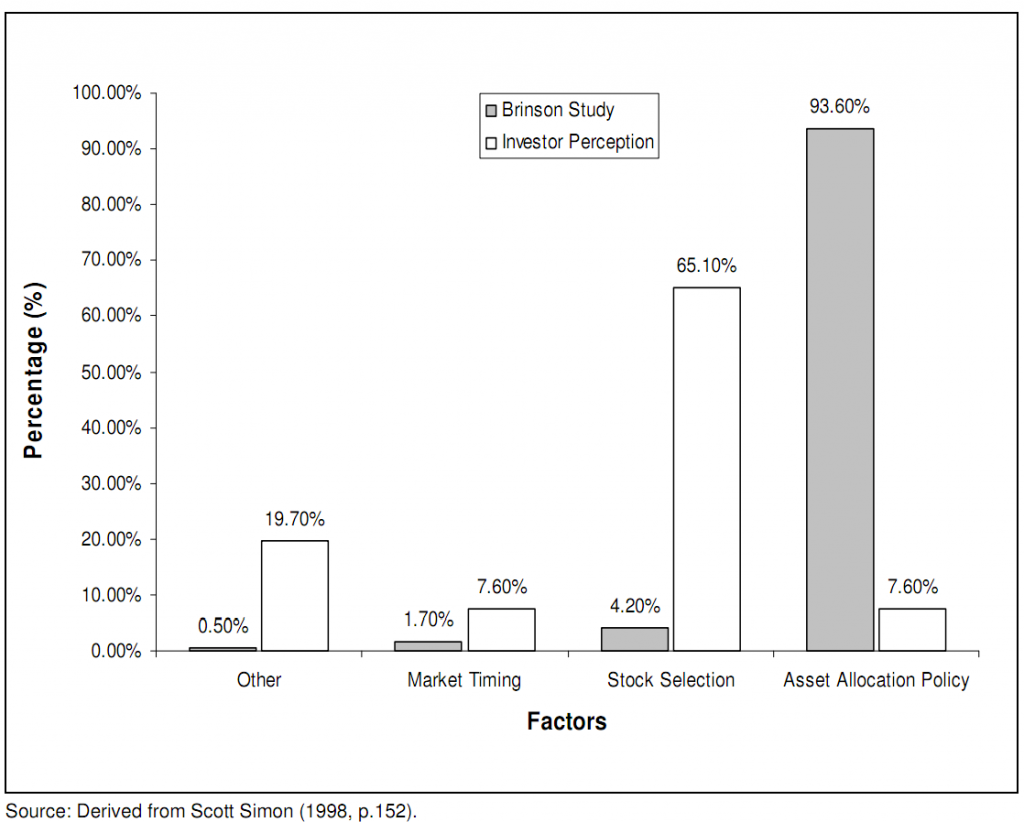

But there are several studies that prove otherwise, starting with a well-known Brinson study that compared investors’ perception of the selection of stocks versus its real importance in terms of investment performance:

What this study concluded is that the most important factor in determining the performance of investments is the assets allocation, by stocks or bonds, and not the choice of securities or moments to invest in the market, contrary to the widespread opinion of investors surveyed.

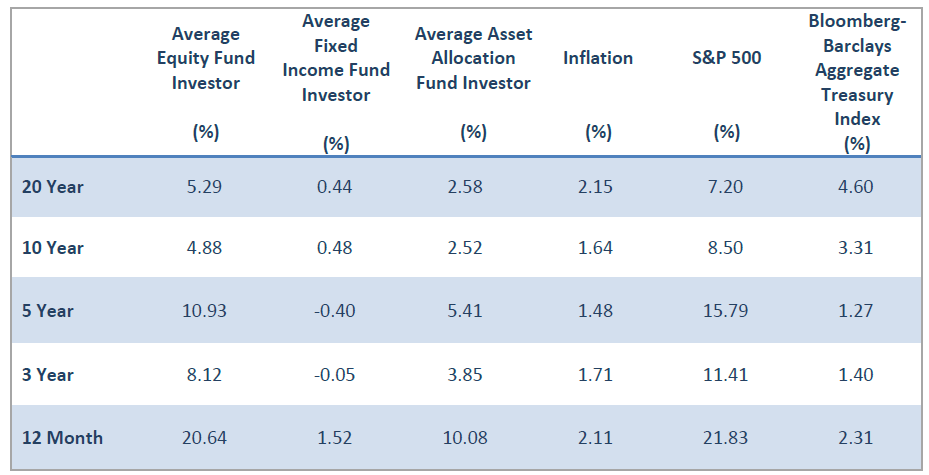

The following table results from a more recent study conducted every year in the USA by Dalbar since 1994 and comparing the performance of profitability rates achieved by private investors on average with those provided by the market in general ( the main indices of each asset class) for the period 1988 to 2017:

.

.

Source: Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behaviour, 2018, Dalbar

The average private investor’s dislocation costs him a lot because his average long-term returns fall far short of those in the market.

There are tenths or small percentage points difference. We are talking about 2% per year for 20 years compared to stocks and more than 4% per year with regard to bonds. Only in the very short term does the average investor get results aligned with the market. From 3-year periods, the investor does not achieve the yields of the markets in general and the differences are accentuated as the investment period increases.

The greater the differences, the worse, and the longer they last, the higher the cost or loss.

Only between 10% and 20% of institutional investors achieve the financial markets returns and it is almost impossible to know in advance who will be successful

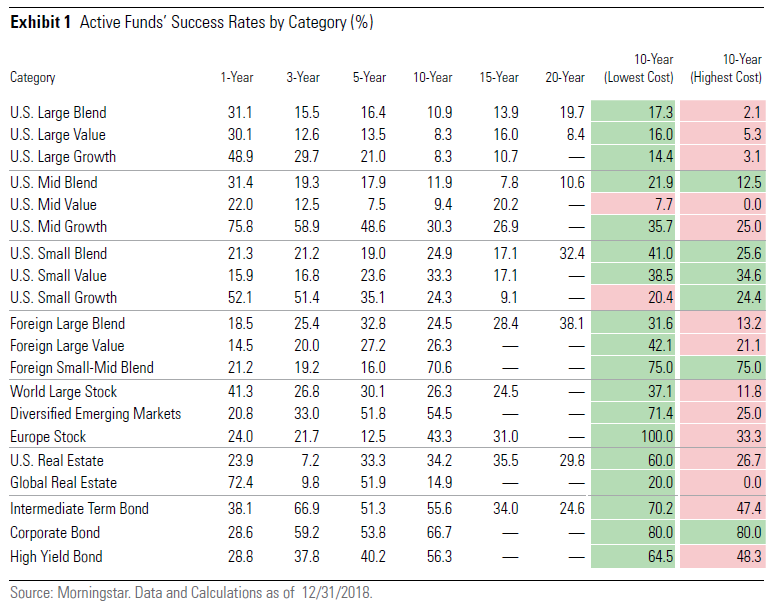

Morningtar conducts a similar study on institutional investors twice a year, covering more than 4,000 US mutual funds that manage more than $12.5 billion (millions of millions) and account for 64% of the mutual fund US market:

Source: Active/Passive Barometer, Morningstar, 2019

Even professional managers also fail to beat the market in most cases. Their success rates in the various investment categories are very low. It should be noted that the effect of the selection of securities and investment costs (management fees and other costs) is combined here.

In the case of stocks of large or medium-sized U.S. companies, only less than 20% of managers reach returns higher than the market at 10 and 20 years. The percentages are slightly higher for stock managers of small businesses and foreign companies, but not even half hit market indices returns on time horizons longer than 10 years.

In the case of bonds, the situation improves slightly, but even so there are only 34% or 20% that can overcome the market returns of treasury bonds at intermediate time limits, in periods of 15 and 20 years respectively.

What history records and the facts prove is the opposite of what investors think: neither the average private investor, not even professional investors, can beat the main indices of the stock markets and bondholders.

Thus, the correct answer to the question of how many securities to invest is that it is better to invest in a broad set of securities, or rather, in the market in general, once again following the logic of diversification.

However, despite all these studies, this reality is hard to accept for some investors because beating the markets seems so simple…thought if there were many would be rich

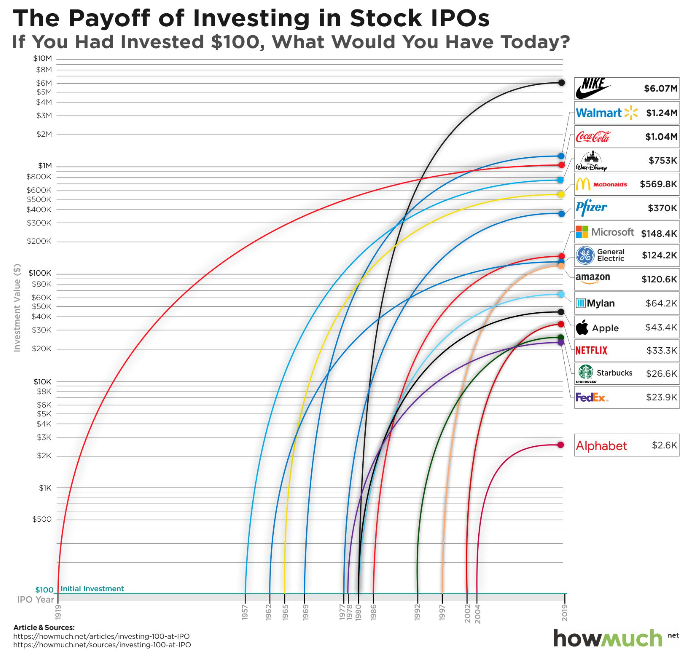

No one has any doubts that today and looking back, the best investment we would have made in recent decades would be to put all our money into Microsoft IPO in 1986, or Apple in 1980, or even in most technology companies.

The results would be fantastic. At Microsoft, in just over 30 years we would have turned $100 into $148,4 thousand. At Apple it would turn out $43,4 thousand. And in the technology companies, in general, capital growth has been very good (though there are better ones like Nike, for example).

The problem is that when we invest, we are not looking at the rear-view mirror or the past, but we look ahead and try to look forward to the future.

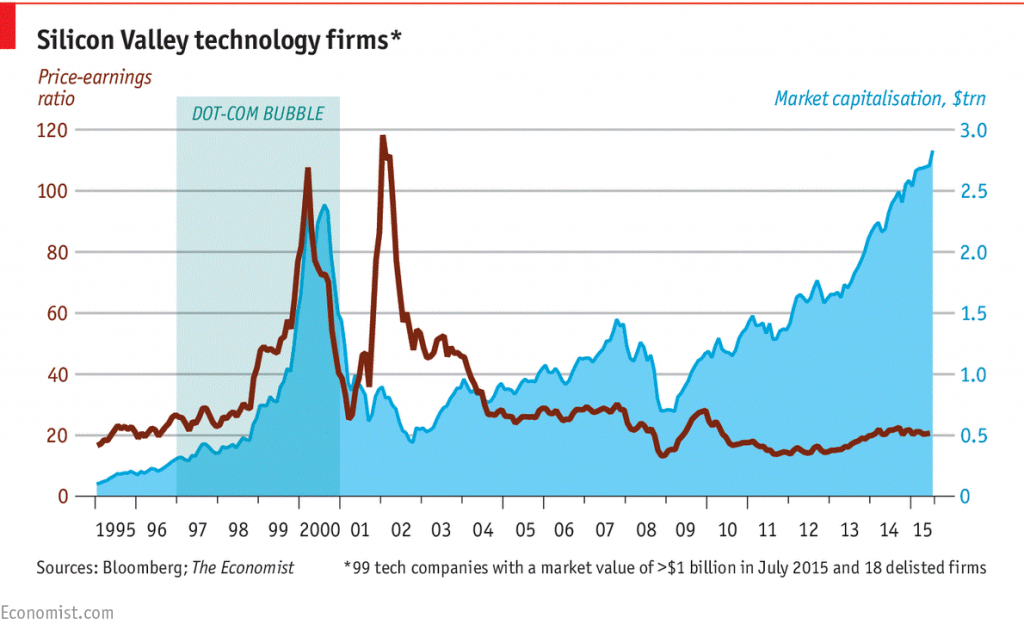

The decision to invest in technology today looks easy because given the revolution and rapid technological dissemination we take this situation as evident.

However, if we remember how we live investments in this sector during the period 2000 to 2003 of the crisis of the technological bubble, it no longer seems so evident and clear cut. With the devaluation of more than 80% of the value in just 2 years, many of us sold much of these investments and it cost us to reinvest in the surviving companies.

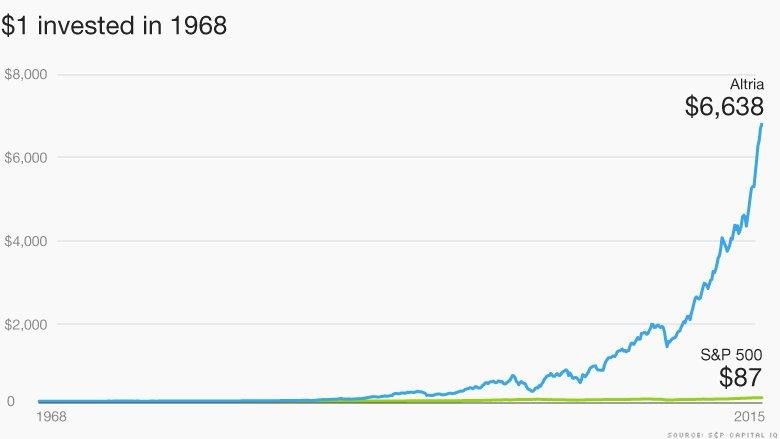

On the other hand, who knew that one of the stocks that has appreciated the most in recent years was from a tobacco company, Altria?

With all regulation to the contrary, including the unequivocal and irrefutable medical demonstrations of major health ills and being the main cause of chronic and terminal diseases, the prohibition of consumption in public places, the social stigma of smokers, etc., Altria (formerly Phillip Morris) had an appreciation almost 100 times higher than the average of the 500 largest US companies between 1968 and 2015.

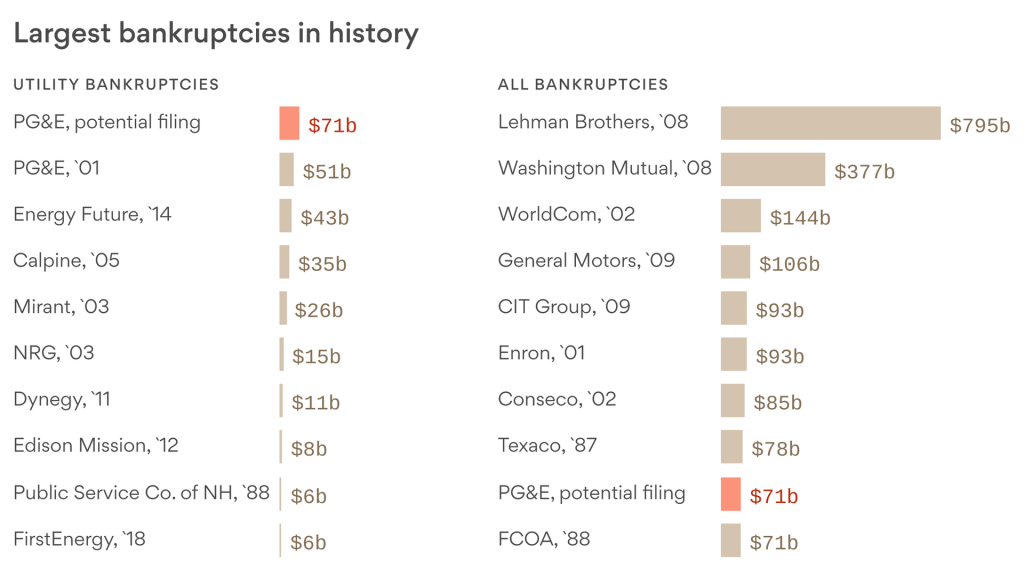

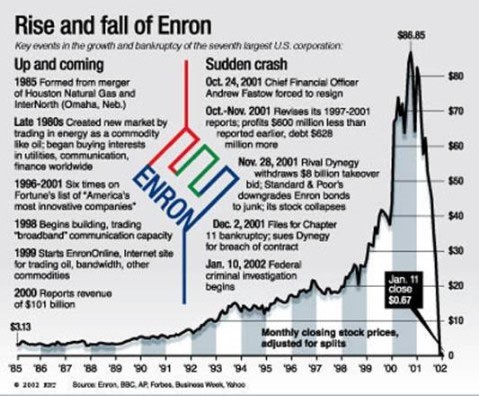

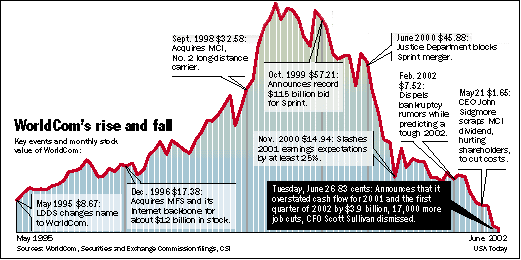

Not getting this right is the least. Much worse would be if we had made large investments in Enron, Worldcom or Lehman Brothers when they were fashionable. At the time they fell apart they were large companies, of reference in their industries, and from one moment to the next they imploded.

We would have lost all the invested capital.

It is not easy to choose the best stocks than the market in general because the market odds do not

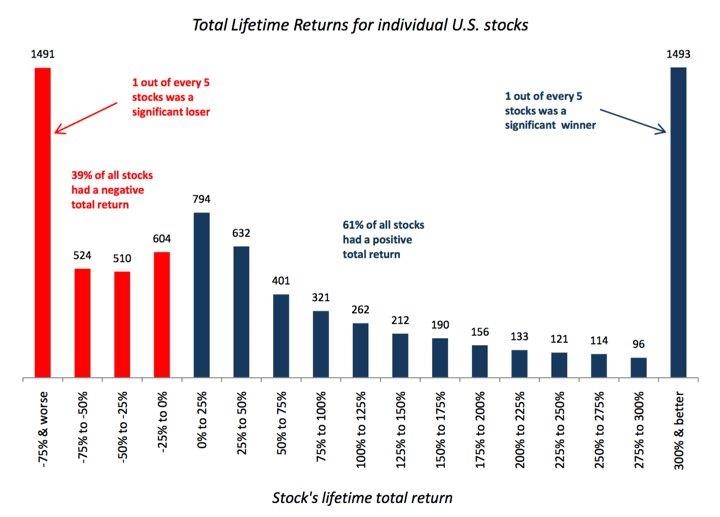

Okay, it’s not easy to pick the best and worst companies. Can we at least trust the stain? No, either.

A recent study presents the following graph concluding that 1 in 5 shares have a lifetime positive return of more than 300%, but also so many others have a negative return of more than -75%. More: 61% have positive and 39% negative returns. With this dispersion, how can we be able to differentiate them?

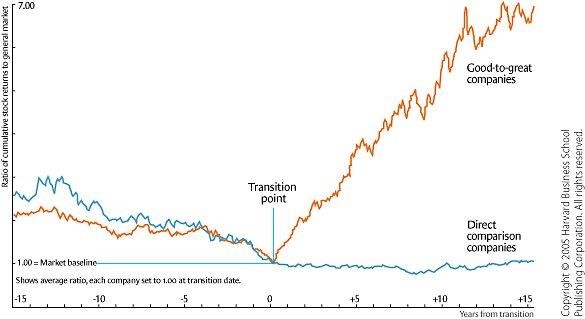

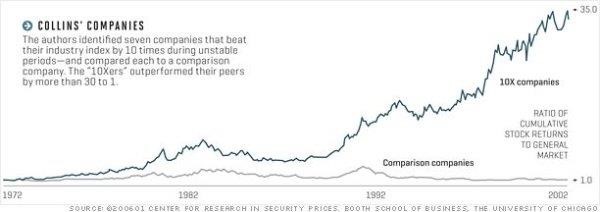

Jim Collins’ reputed studies show that we only know how to distinguish the best companies “a posteriori”

Jim Collins is an economist who wrote some of the greatest management bestsellers of all time: “Good to Great” and “Built to Last” using a methodology of comparing competitors or industry peers-

One of the main conclusions is that at every moment it is very difficult to identify the companies that will surpass the others. He concluded that there are traits or patterns that distinguish them. It follows, however, that these traits are only detected “a posteriori” and “not a priori”.

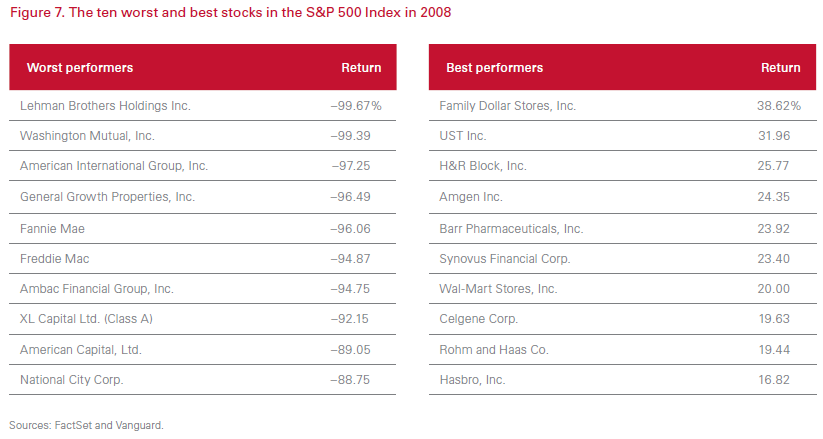

Not even in times of serious financial crisis, such as 2008, it is not easy to predict in a timely manner which investments will perform better or worse:

Diversification in investments improves the risk/returns trade-off and it requires an investment in 30 or more securities

It is the process of combining individual investments or securities into an investment portfolio.

The aim of diversification is to lower risk without reducing returns or increasing returns to the same level of risk.

The benefits of diversification only exist when investments or securities are negatively correlated.

Buying securities, stocks or bonds from collective investment vehicles such as mutual funds provides a source of diversification with bearable costs.

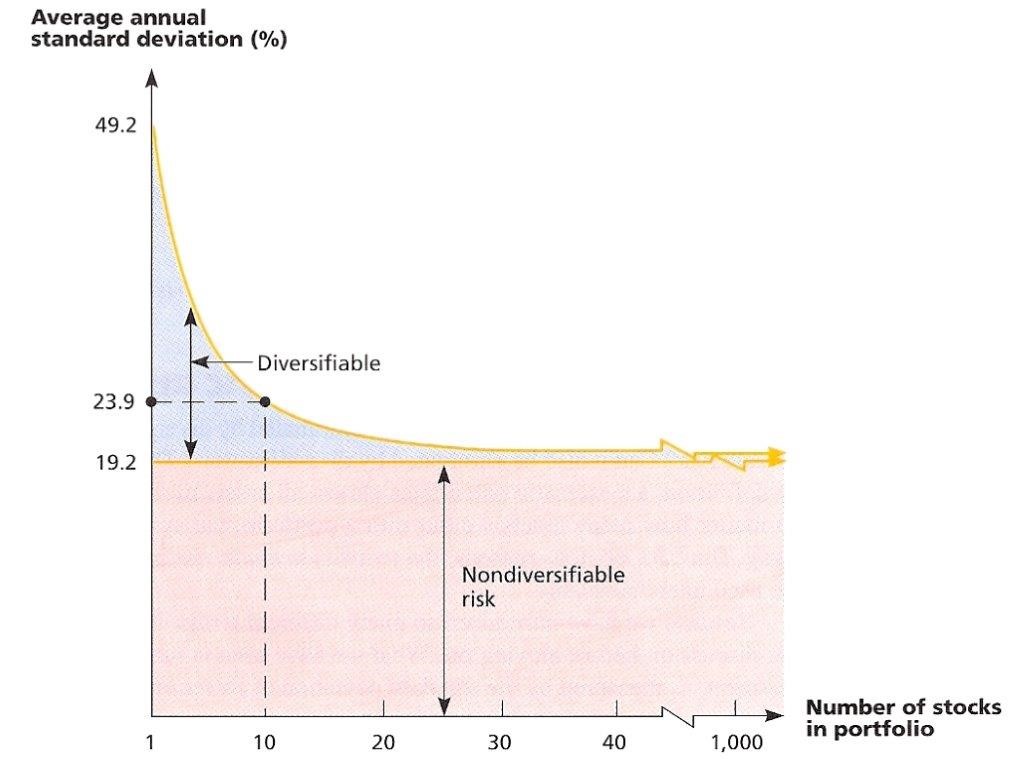

Distributing investments across multiple securities eliminates some degree of risk but not their entirety.

So, what we should do is not choose individual securities, but invest in a set of securities or diversify.

How many securities are enough? A study has shown that if we invest in more than 30 securities, we already diversify individual risk and are only subject to the unavoidable market risk.

We will see in another post that the best investments are those that represent the desired sub-assets classes, have the largest and best diversification in this sub-asset class and the lowest investment costs.