Temptations, vices and other pitfalls of seeking market timing

What is market timing?

What are the implications of market timing?

#1 We lose money

#2 We also lose money because we chase past returns

“If you can look at the seeds of time, and say what grain will grow and what will not, talk to me.” —William Shakespeare, Macbeth

“The only function of economic forecasting is to make astrology seem respectable.” — John Kenneth Galbraith

“He was the greatest, the Maestro. Only if we look at his record, he was wrong about almost everything he ever predicted.” economist about Alan Greenspan

This article is the first of a set of articles dedicated to the theme of seeking to choose the times of investment in the stock market.

Many consider that one should choose the times to be invested in the stock markets, that is, to make the “market timing”.

In other words, we must be invested in the positive cycles of the markets and disinvest in negative cycles.

Obviously, this idea is based on the assumption that we are able to anticipate the moments and cycles of the markets.

We think that it is not possible to do so, as we will try to prove.

In addition, doing so is very expensive for us.

As investors, we are subject to biases that lead us to market timing at very considerable costs.

Temptations, vices and other pitfalls of seeking market timing

Financial markets, especially stock markets, are volatile.

They fluctuate a lot in the short term and from time to time have corrections, with less or greater severity.

Trying to buy at a cheap price and sell at an expensive price should not be challenged.

Different is to try to buy at the lowest prices and sell at highest prices, which is what the “market timing” seeks to do.

If we are able to do so, there is nothing to say, or rather, what we have to do is say nothing for anyone to copy, and get rich.

However, very few, or even none, can do so systematically and consistently.

Who does “market timing”, faces other questions: What to do when you are not invested? Keep in cash? For how long? When do you get back to the markets?

You usually leave too late and you also re-enter too late.

Even if there is someone who has the gift, the ingenuity or the luck to leave in time to avoid a sharp correction, you will hardly be able to arrive in time to catch the first strong valuations of recovery.

This is because there are many so-called technical corrections, of more than 10%, that mix with the major corrections, exceeding 20% (“bear markets”).

Often, some people don’t even expect so much.

Just a correction of 2 to 3% in a day or 5% to 7% accumulated a few days to be anxious.

Often these technical corrections reach more than 10% or 15% and markets return in great force.

It’s called a reversal to the mean.

We should not even worry about these corrections because they are small in the general context of earnings, too frequent to be predictable, and any reaction we have is usually to lose money.

Even major corrections, those of market crises above 20%, are very difficult to predict.

So difficult that whoever gets it stays in history as one of the few who did it.

And more importantly, what the financial story tells us is that the market always ends up recovering and making new maxims.

We don’t know what’s harder, if you do the market timing, or if you do the stock picking.

These attempts are equivalent to trying to hit the eye of the fly or the lottery jackpot.

What is market timing?

Choosing market times or moments is the strategy of making decisions to buy or sell stocks trying to predict future market price developments.

The forecast may be based on a market perspective or economic conditions resulting from technical or fundamental analyses.

It is an investment strategy based on the prospects of an aggregate market and not on a particular financial asset.

The efficient market hypothesis is the assumption that asset prices reflect all available information, which means that it is theoretically impossible to “systematically beat the market”.

What are the implications of market timing?

#1 We lose money

It is shown that we lose money when we try to choose the moments to invest in the market or make the market timing.

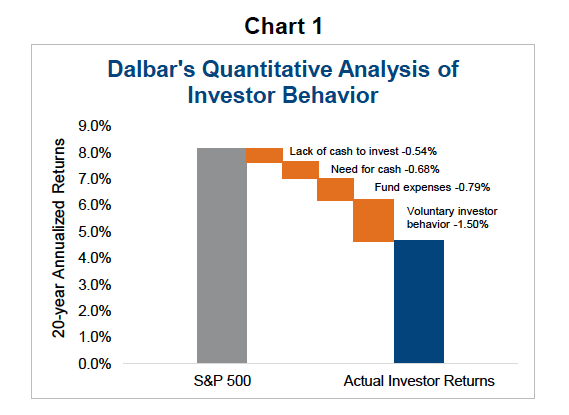

According to Dalbar’s annual studies, titled Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behaviour, investors lose about 1.5% a year as a result of their behavioral biases, in which the demand for market timing is one of its biggest reflexes.

The main biases are the aversion to loss, the timeliness or recent memory, the illusion of control, the excess of optimism and conservatism.

All result from behaviors and actions of choice of the “good and bad” moments of the market.

The impulsivity of reactions and the turnover of transactions are the two most important manifestations of this demand for market timing.

The stock investor loses a total of about 3.5% of average annual returns compared to the S&P 500 index, the largest loss from behavioral biases.

The total loss represents almost 40% of the average returns of the S&P 500.

And the biased investor behavior represents about 40% of the total loss.

These losses are felt for at least 20 years, which has a major impact on the loss of invested capital due to the compounding effect of income.

#2 We also lose money too because we chase past returns

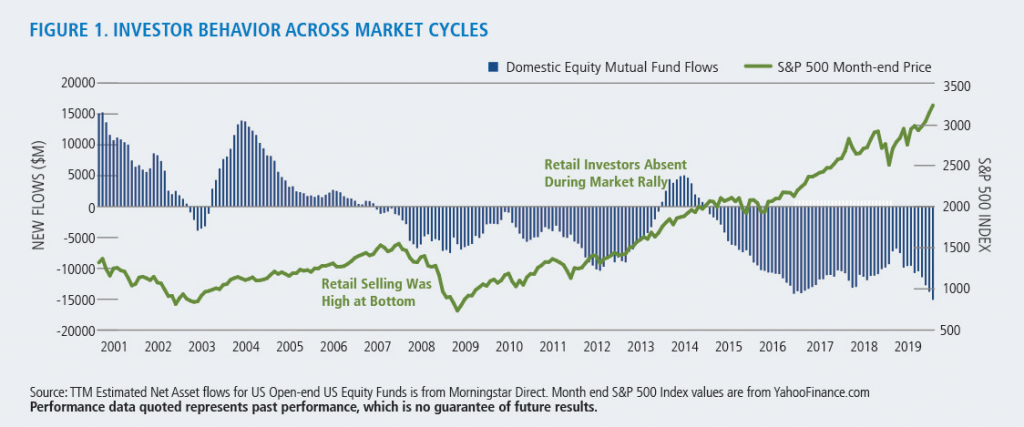

Another evidence that we lose money trying to make the market timing is by analyzing the flows of funds invested in the market.

The following chart shows the evolution of inflows and outflows of capital invested in equity investment funds by individual investors and the returns of the S&P 500 index between 1995 and 2019:

If we look closely we see that individual investors start selling when the market starts to fall.

And they reach the maximum value of accumulated sales at the time the market begins to rise.

This means that these investors are underinvested when the market is cheaper or offers interesting returns.

Investors sell low and buy high, doing precisely the opposite of what they want and are told to do so.

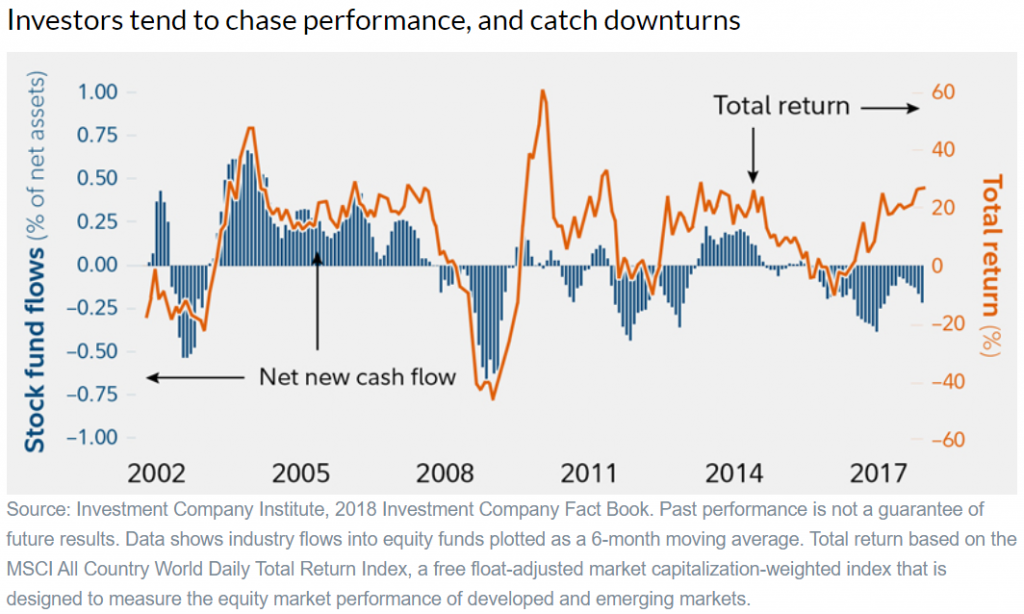

The following graph presents this reality in another way, presenting the capital flows invested in the funds alongside the returns of the MSCI ACWI index, which allows better evidence of what was said:

There is a high correlation between fund flows and stock market returns.

We buy when the market goes up and sell when it falls.

What’s even worse is that when it falls, especially in crises (e.g. 2000 and 2007), sales start after a few falls and continue on an accelerated pace until the market reaches its lows.

That is, investors sell in the falling prices and end up selling more at the lowest prices.

The so-called capitulation takes place, at which point investors can’t resist losses and sell almost everything.

Then, when the market begins to recover, investors practically do not act. Only after some time of market valuations do they start buying, losing the strong initial recovery.

This shows that investors do “market timing”, that is, they go after the market (“chase the market”).

They invest more when the market is rising and uninvest when it goes down.

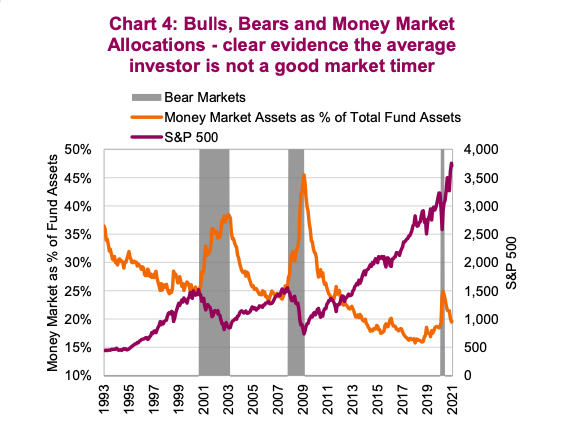

This reality is also evident in the following chart showing the evolution of the S&P 500 with the percentages of allocation to monetary investment funds by individual investors between 1993 and 2021:

Investors chase the market, buying when it goes up a lot and selling when it falls a lot.

Individual investors end up being less invested – higher allocation to liquidity – when the market begins to recover, as well as being overly invested – lower allocation to liquidity – when the market is at maximums.

In the second part of this article we will develop the theme of the impossibility of doing the “market timing” and we will address two other consequences that result in losses even greater than these.