To succeed in investments, we have to live with the usual and frequent corrections of up to 10% and 20% of the equity markets OR Anatomy of an equity market correction

Equity markets show a very good historical performance, but not linear due to corrections

The definition of equity market corrections is situations in which the market depreciates between 10% and 20% since its previous peak or maximum level, also called technical corrections. When the stock market registers a loss of more than 20% it is said that we are facing a negative cycle, a crisis, or a bear market.

As we shall see, equity market corrections are usual, normal, and frequent. They succeed all or almost every year, and more than once a year.

To better picture this, we purposely chose the image of a 3,000-meter obstacle race.

Investing in equity markets is like a medium-distance race and with obstacles. It is not a 100-meter race, or an explosion. It is also not a race with barriers, which are predictable levels, because they are all the same, they all have the same height, they are the same distance, and each athlete runs on their track. And it be shorter than a 10,000-meter race, let alone a marathon, because you do not have to run such long distances to reach the finish line, which are our financial goals.

Equity markets show a very good historical performance, but not linear due to corrections

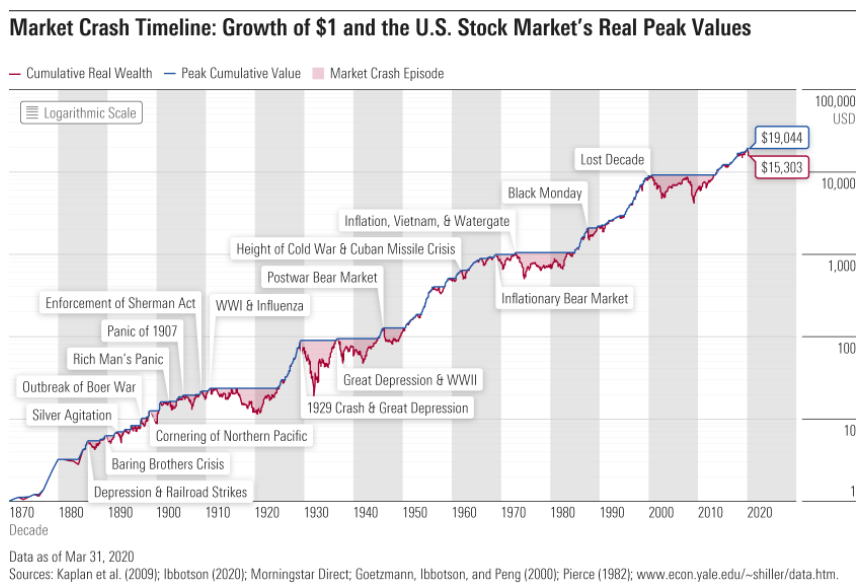

In the following chart we can see the evolution of 1 dollar invested in the US stock market (given by the S&P 500 index) between 1870 and 2020, in real terms or purchasing power, and on a logarithmic scale which means that each range equates to a doubling of the value:

This dollar invested 150 years ago or 5 generations ago by our great grandparents or great-great-grandparents, would have resulted in more than $15,000 in March 2020, at the lowest level caused by the pandemic, after reaching a maximum of $19,000, in terms of purchasing power.

The real wealth created is enormous: more than 15,000 times in 150 years. It is equivalent to an annual real return of 6.5% per year (corresponding to a nominal return of 9% per year less an average annual inflation rate of 3%).

This 6,5% value looks like an almost linear evolution, but it is not (incidentally it is even known by Siegel’s constant).

In fact, there have been advances and setbacks. There are positive periods and there are negatives. There are long, medium, and short-term cycles. There are periods of great expansion or wealth creation, such as 1870-1910, 1919-29, 1950-70, 1985-2000 and 2009-2020, as well as periods of great falls, such as the Great Depression of 1929, the technology bubble of 2000, and the Great Financial Crisis of 2007.

Although it is more difficult to detect, there are many more periods of more moderate climbs and less steep descents.

Market corrections of between 10% to 20% are frequent and often profound, and we need to know them to be prepared to go over them

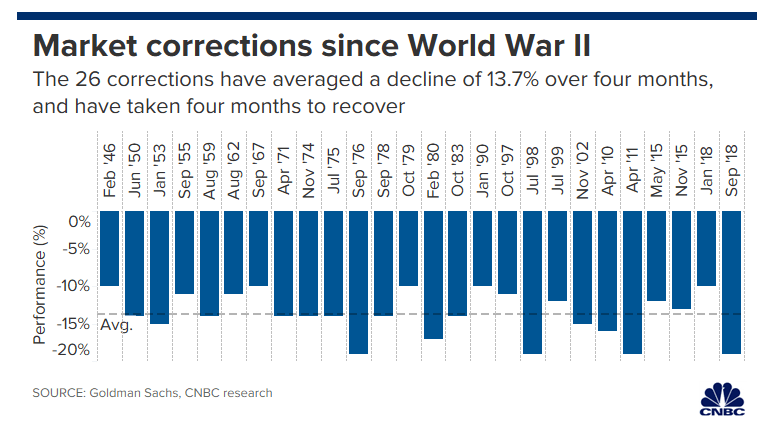

The following graph shows 27 of the 28 corrections (between 10% to 20%) that have occurred since World War II to date (missing the recent March 2020 linked to the coronavirus crisis):

There were 26 corrections that on average recorded a devaluation of 13.7%. They had an average duration of 4 months and were also recovered in 4 months, on average.

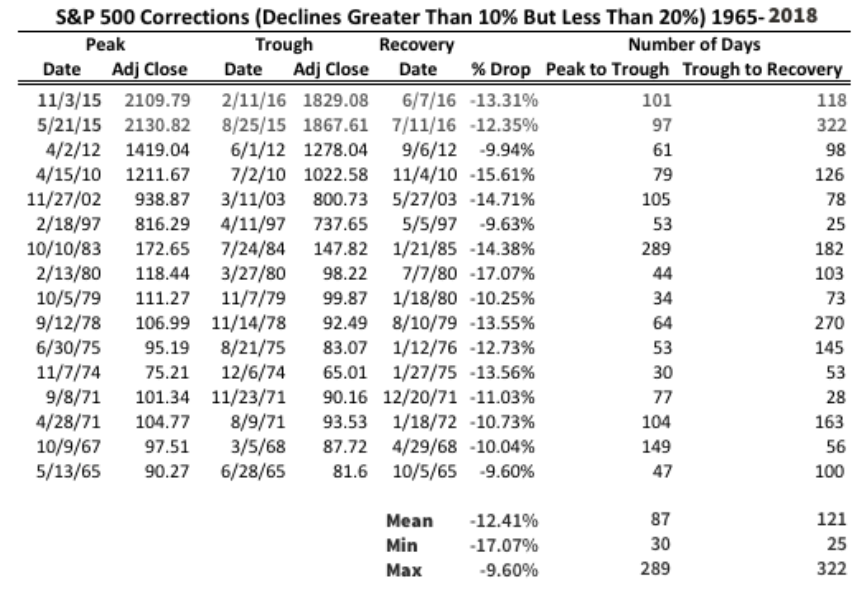

The following table shows these crises in greater detail in the period from 1965 to 2018:

Most crises last less than 3 months, and there was only one very prolonged, that of October 1987 of almost 9 months. Falls are mostly 10% to 12%.

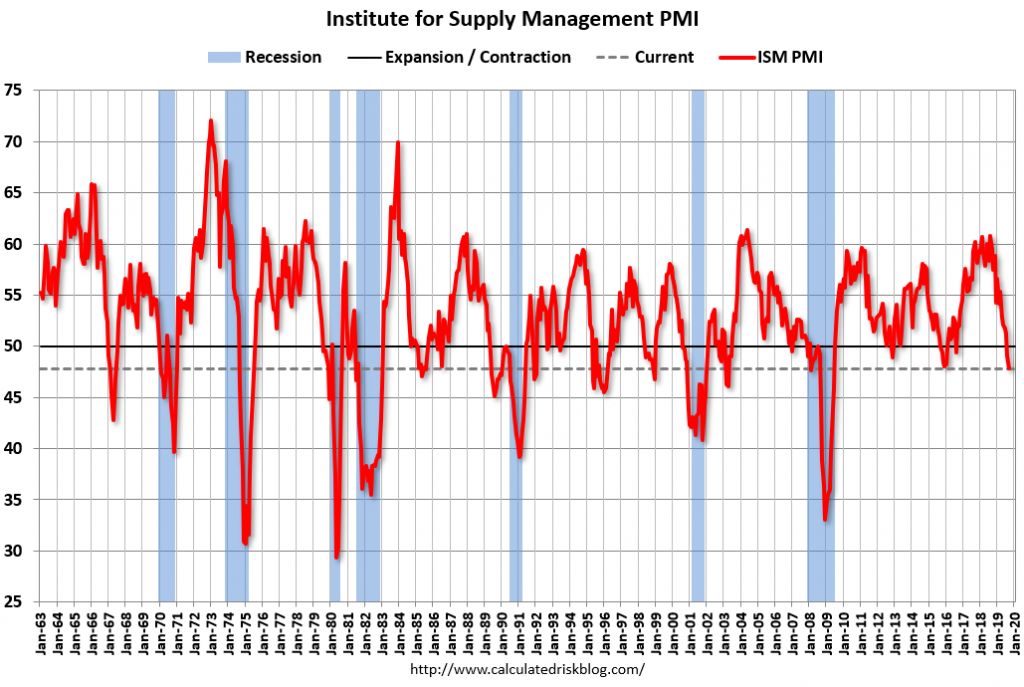

To try to better understand these situations the following chart shows the evolution of the S&P 500 index and the advanced ISM indicator in the period 1962 to 2020:

These are corrections that are not linked to economic recessions, as these give rise to major crises, negative cycles, or bear markets, with steeper declines.

They are usually associated with exogenous events, such as commodity shocks – oil and gold – or market events – economic policy changes, credit rating declines, etc. – and coincide with a slowdown in economic activity evidenced by the fall in ISM.

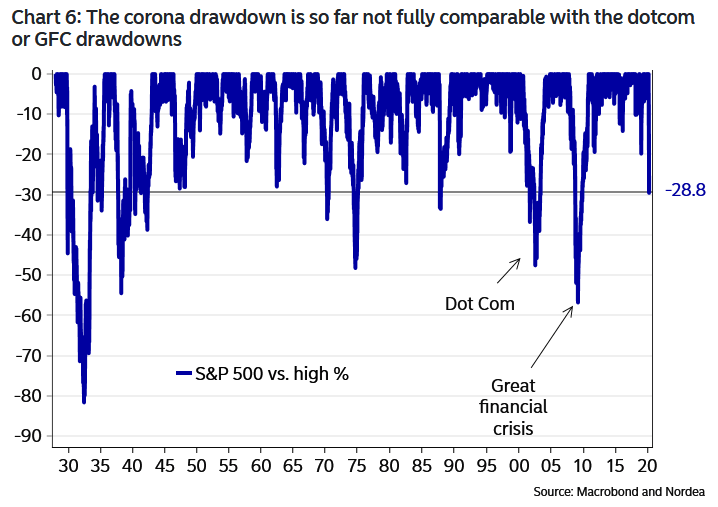

We often live and feel crises through the concept of “drawdown”, which has its advantages, but also inconveniences

The drawdown concept, measured as the negative deviation between a peak and the next minimum level, and associated with maximum potential loss is very useful for preparing, planning and establishing our central allocation of investments, being a good test of risk tolerance and defining the investor profile.

However, it is a bad indicator for us to live crises because it can become obsessive and destabilizing. During crises we often make calculations at everything like those of the drawdown, that is, how much we lose from the highest point of the market. This value often overshadows loss or even lower actual gains. There would be no harm with that if those values were considered as well. We rarely do the calculations to maximum potential gains. This makes us feel more the market’s losses than the gains and pushes us out away from it.

By definition, potential gains or losses are virtual realities. What matters are the actual gains and losses.

We highlight the strong devaluations of more than 80% in the Great Depression, almost 60% in the Great Financial Crisis and almost 50% in the technological bubble. The average drawdown was 28.8%. Rarely exceeded the 30% that marks a bear market. However, drawdowns of 10% to 20% are very frequent.

In graphic terms, it is necessary to keep in mind that each time the line touches the horizontal axis it is because there is a drawup, or an appreciation starting from the minimum level that has been fully retrieved and exceeded.

It is impossible to manage corrections because not only are they numerous, frequent, without pattern and unpredictable, and most importantly, occur in times of positive market cycles

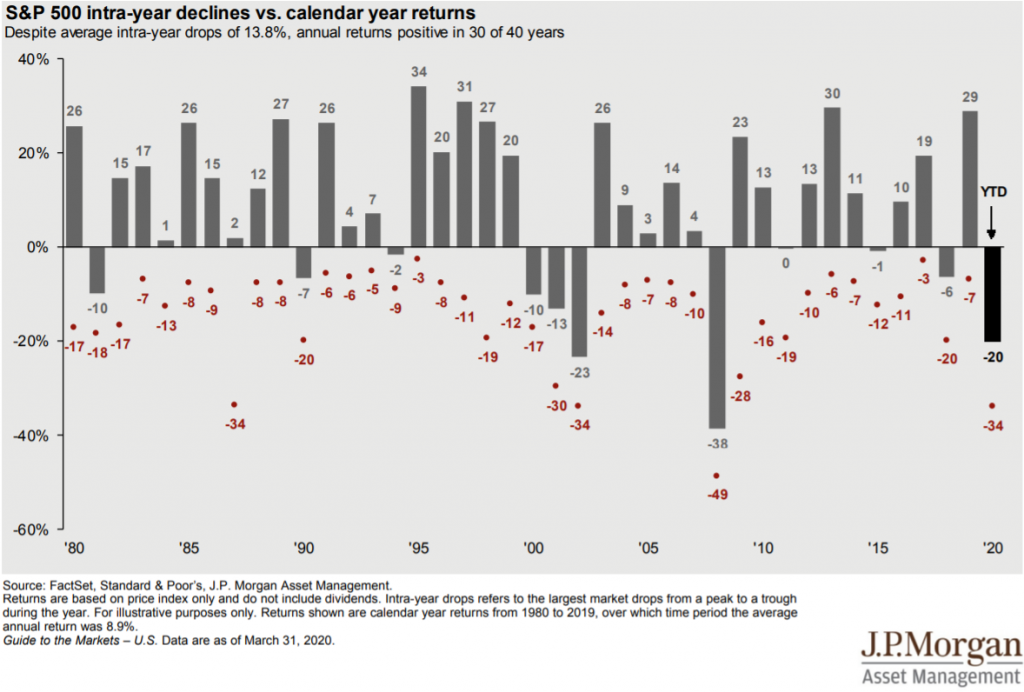

The following graph shows the annual returns and the largest intra-year returns seen by the S&P 500 between 1980 and 2020:

This chart helps put drawdowns in perspective and allows for other conclusions.

There are several occasions when the market losses more than 10% during a given year, but at the end of the year the market ends with positive returns, in some cases even quite positive and above 20%. Intra-annual volatility with this size and frequency is impossible to predict and anticipate.

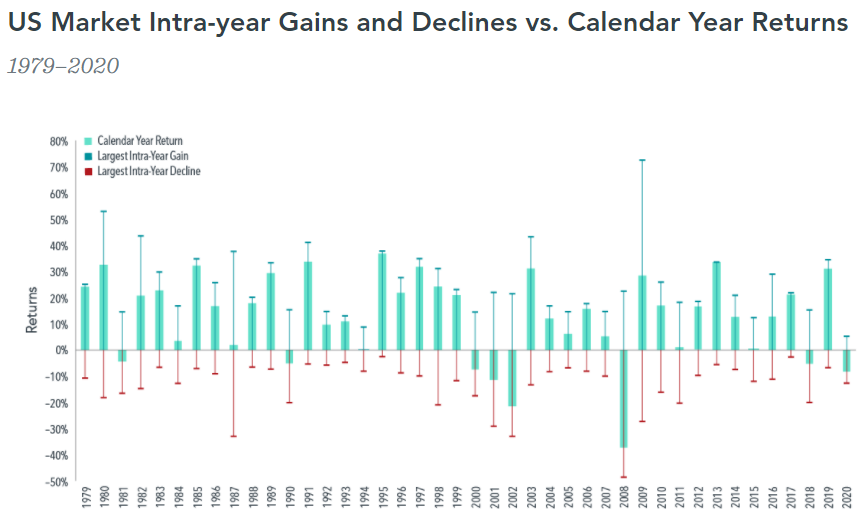

The following graph shows the annual returns, as well as the highest intra-year gains and declines of the S&P 500 index between 1979 and 2020:

Not only are there several significant recoveries from intra-annual devaluations, but we can have very high gains during these years. The years 2009 and 1980 are extreme, but they are very illustrative of this reality.

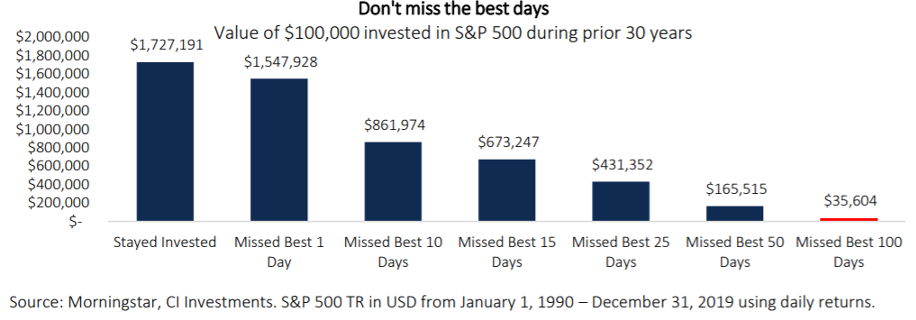

In addition to being impossible to predict corrections, the loss of the best market days has a huge cost.

The following chart shows the effect of losing some of the best days on the market on a $100,000 investment in the S&P 500 over the past 30 years:

We must recall that 30 years are 7,830 working days of market transactions.

If we were invested all the time the capital accumulated after 30 years would be $1,727,000. The loss of the best market day would have reduced that amount by $175,000 or 10%. However, the loss of the top 10 market days would have cut half the accumulated capital, and the loss of the top 15 days would represent a cut to almost 1/3. More serious still, missing out the 25 best days would be to lose 75%, and if it had been the 50 best days, the capital would be less than 10% to what would result if we were always invested. In an extreme case, the loss of missing the 100 best days would result in accumulated capital of $25,000, that is, an effective and large loss of invested capital of about 35%

If, on one hand, it takes a lot of bad luck to always miss the best days, it is also important to keep in mind that even 100 days are only 1.2% of the total days.

To aggravate the situation, the best market days usually arise during crises or even market crashes.

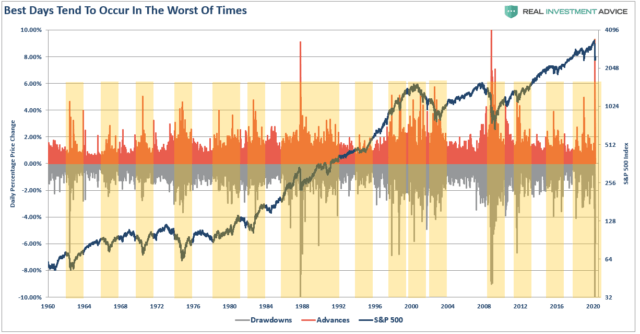

The following chart shows the daily valuations recorded in the S&P 500 between 1950 and 2020:

The two best market days, with 10% or almost appreciation, occurred in the middle of the great crises of 1968 and 2008. It is also easy to see that valuations above 4% have usually succeeded in times of crisis.

It is not surprising that in times of crisis, market volatility is very high. This uncertainty is another reason for being very difficult to predict and above all to manage the times of major corrections.

How should we act on corrections? We should not chase the market, and we must maintain our course and rebalance

Thus, the question arises of how we should deal with market corrections.

We start by seeing what we should not do and that unfortunately is what we normally do: go after the market, that is, sell low and buy high.

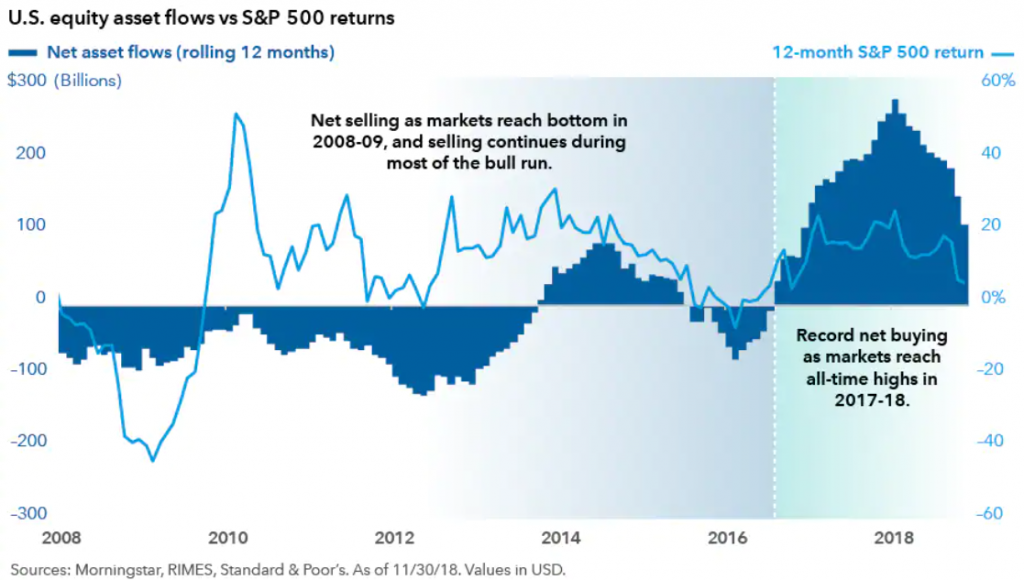

The following chart shows the average 12-month net investment flows in the S&P 500 index (in bars) and the returns of the same 12-month index (online):

When the market fell in 2008 investors were selling more and more with the accentuation of losses. Net sales continued at the same pace until 2011 and with markets already recovering well. These sales increased when returns temporarily declined in 2012 and remained until 2014 despite a comeback to good levels of returns. It was only from that year that net purchases emerged and still timidly, 5 years after the end of the crisis. The return of investment to the markets occurred only in 2017, 8 years of strong market gains after the end of the Great Financial Crisis.

We see that most investors sell after the market falls a lot and buys after rising a lot. They sell at low levels and buy at high levels. It is the opposite of a good strategy.

This reality is the result of various behavioural biases, such as loss aversion, recency or short memory, the herding effect, media noise, etc… that are very difficult to recognize and combat.

The way to avoid these situations is to outline a good financial plan and based on a correct perception of the opportunities and risks of investments and our investor profile. If we are aware that we have prepared and thought about investments, it is easier to understand and act in these situations.

The action we must take in the face of corrections is to validate our decision to diversified asset allocation and maintain course by rebalancing.

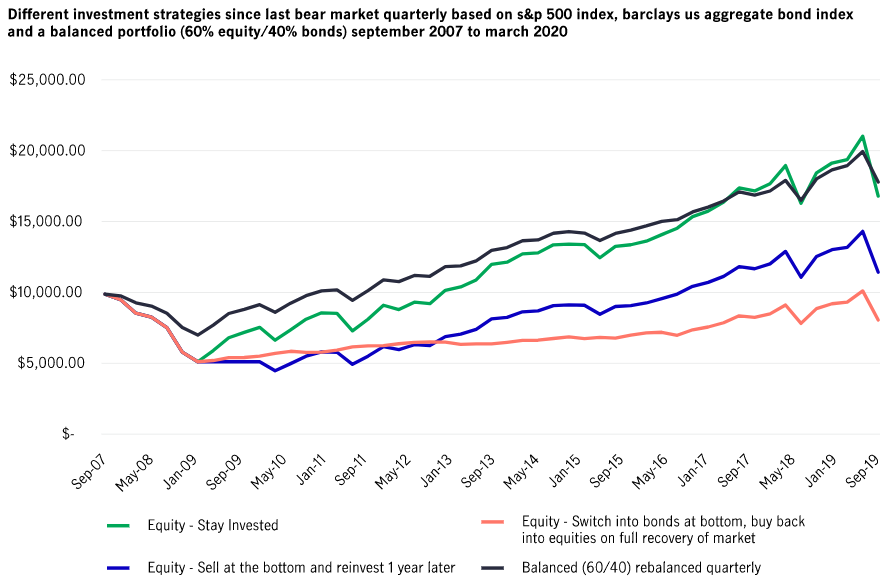

The following graph seeks to typify the importance of a good, diversified allocation of assets and to maintain the course with rebalancing:

The situation shows the development of two investment strategies for an invested capital of $10,000 between September 2007 and September 2019, one 100% in equities and another of 60% in s and 40% in bonds, with quarterly rebalancing.

At the end of the period, the result of the two strategies would be the same, a capital of $17,000 or a 70% appreciation. However, the 60%/40% diversification strategy in stocks and bonds, respectively and with rebalancing, would have had lower volatility than that of 100% in stocks.

We also see what the results of trying to manage the timing in the 100% investment strategy would be in the context of market fluctuations. If the entire portfolio had been sold at the minimum level and reinvested a year later, the final capital would be $12,000. And if you had made a rotation to bonds at the minimum level and returned to the initial allocation after the full recovery of the stock market, the final capital would be $8,000, lower than the initial $10,000.

In the face of a crisis, what we must do is what must always be done: to rebalance. Obviously, in a crisis, rebalancing becomes even more important.

We cannot allow the allocation of assets or investments to be overly altered in the face of large market fluctuations. Rebalancing should be done periodically, preferably once a year, and whenever the composition of the two main asset classes, stocks and bonds departs from the tolerance level of 5% or 10% of the initial allocation established.

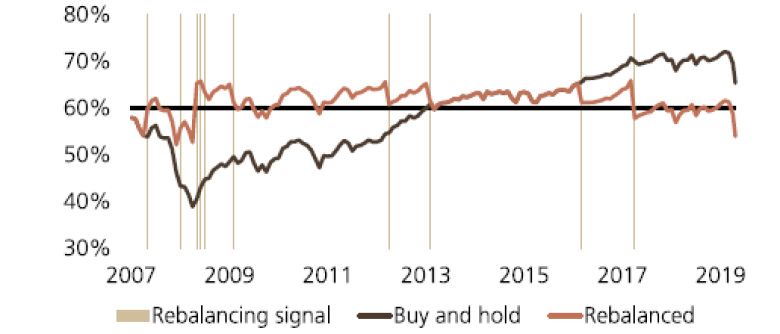

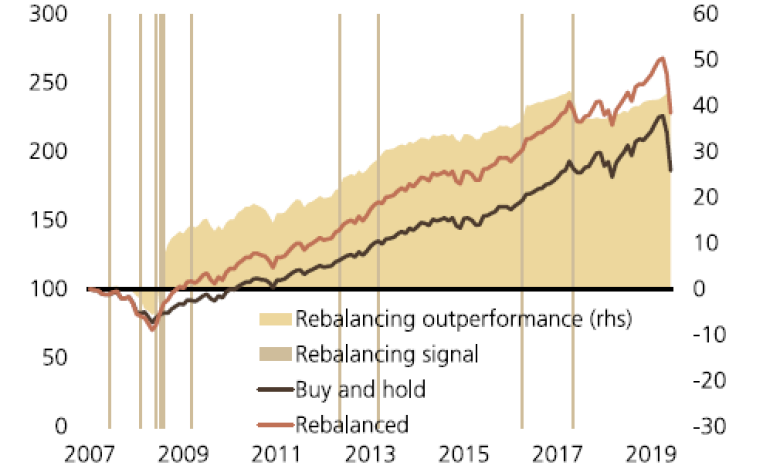

The following chart prepared by UBS shows the effect of rebalancing on a portfolio of investments of 60% S&P 500 equities and 40% treasury bonds between 2007 and 2017 for a tolerance level (or drift) of 5%:

In this case, rebalancing is done whenever the allocation of 60/40 diverts beyond 5 percentage points in absolute terms.

The following graph shows the impact of rebalancing on portfolio performance:

Rebalancing has a clearly stabilizing or buffering effect of the risk of major crises. In this case, it has even provided better performance, although this is not its goal and does not always happen. Its function is to reduce the risk. And it does so by pursuing a winning investment strategy, buying cheaper, and selling more expensive!