China’s construction and real estate crisis is spreading and has a domino effect in other areas

The Weight of Real Estate in the Wealth of Chinese Households

In recent years, the construction and real estate crisis has been combined with the too drastic action of the Chinese authorities to contain the spread of the Covid pandemic

This article is part of a series dedicated to investing in Chinese stocks.

In the first article, a general introduction to the topic was made,including a synthesis of the remarkable performance of economic growth and development in the last 4 decades, as well as the challenges it has faced especially since mid-2015.

In the second article, aspects of China’s strong economic growth over the past 4 decades were developed.

The third article was divided into two parts, the first addressing the performance of the Chinese stock market in the last 4 decades, while the second provided a framework for the prospects of foreign investors’ understanding of the economic reality and the markets.

In previous articles we have already developed the size and weight of the Chinese economy in global terms, its enrichment in recent years, as well as its convergence with the most developed countries.

Also in previous articles we have addressed the growth of investment in emerging equity markets, as well as their attractiveness, with emphasis on the Chinese market.

In another article, we also delved into the specifics of the structure, functioning and activity of the Chinese stock market.

This article, divided into two parts, begins to develop the main challenges of the Chinese economy.

In it we analyze how it all began, the problem of construction.

In the first part we looked at the problems of construction companies.

Now we will see the effect on the economy and households.

It was thought to be the core problem, coupled with the draconian Covid response policy.

But appearances are often deceiving.

The problem is deeper and more structural, as we will see in subsequent articles.

China’s construction and real estate crisis is spreading and has a domino effect in other areas

In addition to the direct impact on GDP, the construction and real estate crisis caused other indirect losses.

The crisis caused heavy losses to the shareholders of the affected real estate companies, as well as to domestic and foreign bondholders.

To the extent that the debt of these companies is mostly concentrated in Chinese banks, especially state-owned ones, they have also incurred serious losses.

Many vendors, subcontractors, and workers were not paid for their services.

The decrease in activity has resulted in higher unemployment.

Many Chinese who bought properties from these companies are increasingly at risk of receiving nothing.

The Weight of Real Estate in the Wealth of Chinese Households

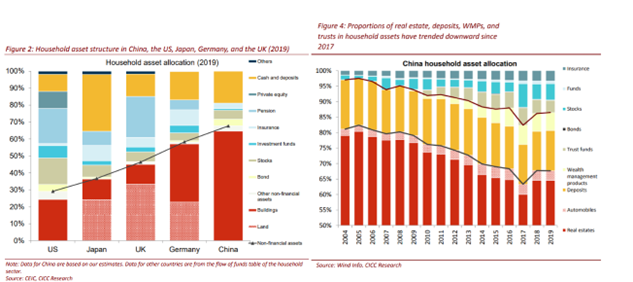

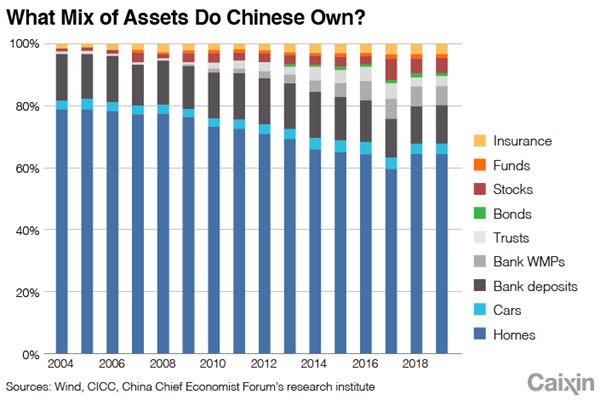

China has one of the highest rates of homeownership in the world, which reached 90% in 2020.

In large part, this is due to the fact that property is seen as a source of economic stability and security.

A huge proportion of personal assets are tied up in real estate in China – up to 70% of household wealth is in property.

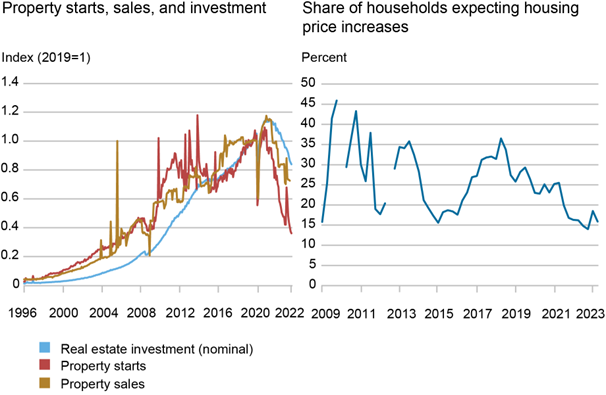

The steady rise in house prices also meant that property was increasingly seen as a lucrative investment:

With up to 70% of Chinese wealth invested in real estate, the fall in real estate prices makes the Chinese poorer and the resulting negative effect of wealth will cause a contraction in consumption:

In addition, land sales to developers accounted for about 40% of Chinese local governments’ revenues, but reduced construction activity by developers caused a drop in revenue.

Internally, the repercussions are less output, less investment, less wealth and higher unemployment.

And as a consequence, greater savings and less consumption, which even more retracts the product, indirectly, to the extent that families spend less to protect the future in a society in which social security is incipient.

Externally, distrust has increased with the losses of investments in stocks and bonds of Chinese construction companies. These losses were passed on to the banks listed on the stock exchange through defaults.

In addition, the mistrust has spread to other sectors, generally affecting almost all Chinese companies listed on the domestic and international markets.

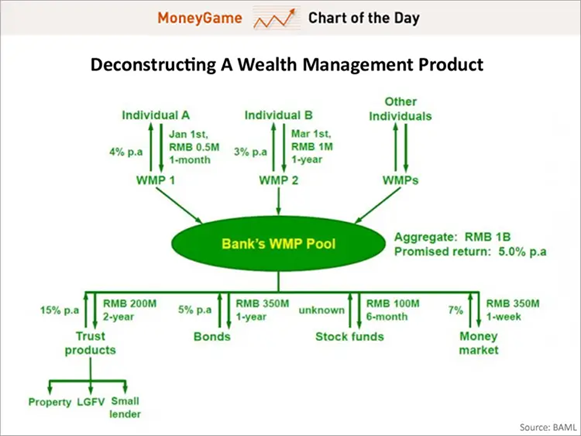

Wealth management products (WMP) owned by households and managed by trusts or shadow banking have made large loans to construction and real estate groups, the losses of which further aggravate this situation

Trusts, or shadow banking, have become an important part of the economy since the 2000s, providing money to many private sector companies, particularly property developers.

They have become a pillar of the non-bank financial system – also known as shadow banking – which has come to represent a significant percentage of China’s GDP.

They are financial institutions that mix banking, wealth management and hedge fund activities, offering investment products to wealthy institutions and individuals.

They exist to provide credit to parts of the economy that have traditionally struggled to access financing from traditional banks, such as real estate and mining.

The trusts have been instrumental in financing China’s property boom, which since 2008 has been one of the main drivers of its economic growth.

This makes them particularly vulnerable to contagion from the current downward spiral in the housing market. Although the data is unreliable, official data indicates that 6% and 7% of its loans are for real estate, while private estimates. estimate the exposure to be 30-35%.

The trusts lent to these companies on the basis of funds and wealth management products with a guaranteed rate of return (“shadow banking”) that they sold and borrowed from Chinese households:

China’s trust industry is valued at $2.7 trillion.

In recent years, the construction and real estate crisis has been combined with the too drastic action of the Chinese authorities to contain the spread of the Covid pandemic

China’s disappointing post-COVID recovery has raised significant doubts about the underpinnings of its decades of impressive growth.

Expectations were that once China abandoned its draconian COVID rules, consumers would return to consuming more, foreign investment would resume, factories would ramp up production and land auctions, and home sales would stabilize.

Instead, Chinese buyers have increased savings, foreign companies have divested, manufacturers face diminishing demand from the West, local government finances have shrunk, real estate groups have defaulted, and state-owned banks have suffered heavy losses.

This means that the construction crisis and the drastic response to Covid are not the only problems, nor perhaps the biggest ones.

They are, of course, the most visible and conjunctural, but there are other deeper and more structural problems.

The dashed expectations have partly vindicated those who have always doubted China’s growth model, with some economists even drawing parallels with Japan’s bubble before its “lost decades” of stagnation from the 1990s onwards.

But a concrete long-term roadmap for debt relief and economic restructuring has yet to be defined.

Whatever choices China makes, it will have to take into account an aging and shrinking population, as well as a difficult geopolitical environment as the West becomes wary of doing business with the world’s No. 2 economy.

These are the topics that we will cover in the following articles.

In the following articles, we will continue to delve into each of these aspects and the consequences regarding the interest of the Chinese stock market for foreign investors.

This central question of the attractiveness of the Chinese market is very pertinent because, as we know, investing well means diversifying risks, doing so, above all, in the world’s largest economies and companies, and privileging those that are world leaders and consumer goods, in order to put the economy to work for us.