The reasons are deeper and more structural

The recipe of the growth model of the past does not work in the present, nor will it work in the future: the drivers of investment and exports versus private consumption

The wastes of the unbridled race for growth

There was no transition from the model to a private consumption base, which was essential

But China has and maintains one of the highest savings rates in the world, both nationally and householdly, and there is no prospect of change

This article is part of a series dedicated to investing in Chinese stocks.

In the first article, a general introduction to the topic was made,including a synthesis of the remarkable performance of economic growth and development in the last 4 decades, as well as the challenges it has faced especially since mid-2015.

In the second article, aspects of China’s strong economic growth over the past 4 decades were developed.

The third article was divided into two parts, the first addressing the performance of the Chinese stock market in the last 4 decades, while the second provided a framework for the prospects of foreign investors’ understanding of the economic reality and the markets.

In the previous two articles, we began to develop the main challenges of the Chinese economy.

In this article we analysed how it all started, the problem of the crisis in the construction sector, addressing both the direct and indirect impacts on the product.

It was thought to be the core problem, coupled with the draconian Covid response policy. But appearances are often deceiving.

The problem is deeper and more structural, as we will see in the following articles, divided into several parts that address different aspects.

This first part focuses on the model of economic growth based on public investment and exports that has worked in the past, and that is unlikely to be maintained in the future.

In previous articles we have already developed the size and weight of the Chinese economy in global terms, its enrichment in recent years, as well as its convergence with the most developed countries.

Also in previous articles we have addressed the growth of investment in emerging equity markets, as well as their attractiveness, with emphasis on the Chinese market.

In another article, we also delved into the specifics of the structure, functioning and activity of the Chinese stock market.

The reasons are deeper and more structural

Investors’ losses in Chinese equities worry us about Beijing’s lack of effective policies to trigger a sustainable economic recovery.

China’s economy grew by 5.2% in 2023.

This was the slowest pace of expansion since 1990, with the exception of the three years of the pandemic until 2022.

International economists widely expect the country’s growth to slow further this year to around 4.5 percent and fall below 4 percent over the medium term.

While this may seem reasonable for a major economy, it is far below China’s double-digit growth over the past few decades.

The country could be facing decades of stagnation ahead, analysts said, as the slowdown is structural in nature and will not be easily reversed.

The construction and real estate crisis is a problem to be solved. It is obvious that the drastic response to Covid has delayed the recovery of economic growth. But these are the visible parts of the iceberg.

There are deeper and more structural issues that explain the economic slowdown, such as the growth model, demography and ageing, politics and geopolitics.

The recipe of the growth model of the past does not work in the present, nor will it work in the future: the drivers of investment and exports versus private consumption

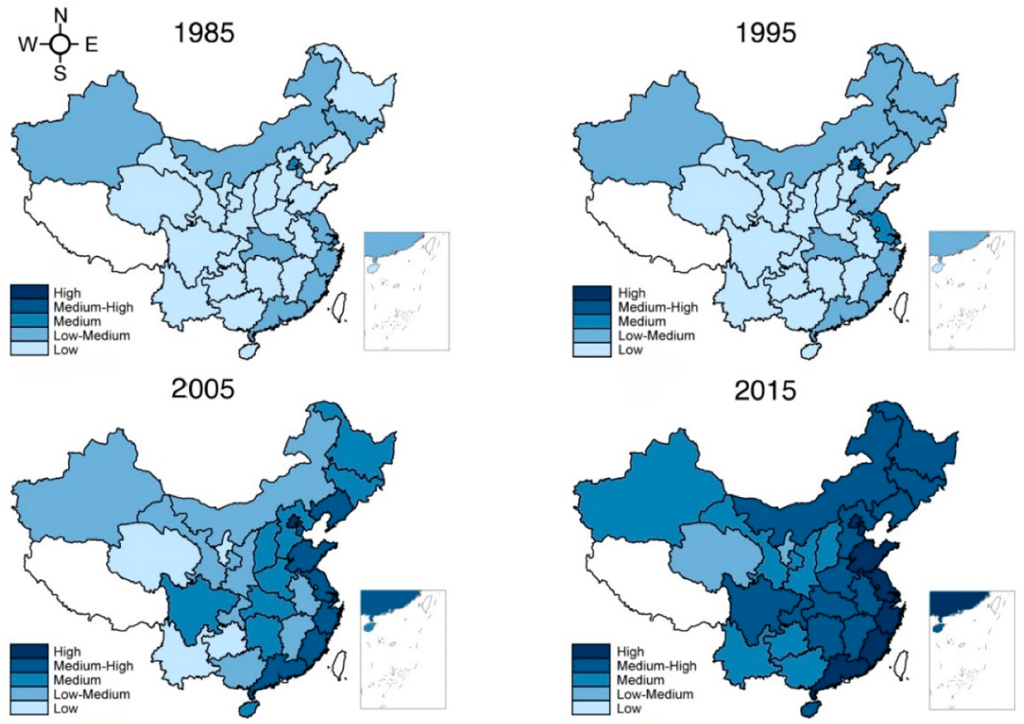

China’s economic growth over the past four decades has been based on public investment and exports.

These were years of strong investment in infrastructure and urbanization, which removed a large part of the population from the countryside to the cities.

These were also years in which cheap labour ensured unbeatable competitiveness in international markets, boosting exports.

China has grown and developed a lot. Populations have become richer. Poverty decreased and a large middle class emerged.

We have moved from an underdeveloped economy to a developing economy, and at a rapid pace.

China’s growth in global terms in recent decades has been impressive, as we can see in the following link:

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/china-economic-growth-history/

That growth began to slow a decade ago.

Not only is it not surprising, as was expected.

Labor costs have risen, spending on providing the public services needed by a more urban and demanding population has risen, imports have also grown to meet the needs of this wealthier population, and external competitive advantages have diminished.

So far, nothing new. It is the law of diminishing marginal returns in a functioning economy.

The Wastes of the Unbridled Race for Growth

However, in this whole process, there has been a huge amount of waste. Worse than that, growth has been rampant.

Rapid urban growth has given way to ghost towns, leaving completely deserted towns that were halfway to the movement from the origin of the countryside to the more developed cities of the coast and the richer provinces, just as happened in the days of the Wild West in the USA:

The same happened with some infrastructures, whose rapid construction did not excel in quality and robustness, requiring constant repairs and maintenance, with the inherent costs.

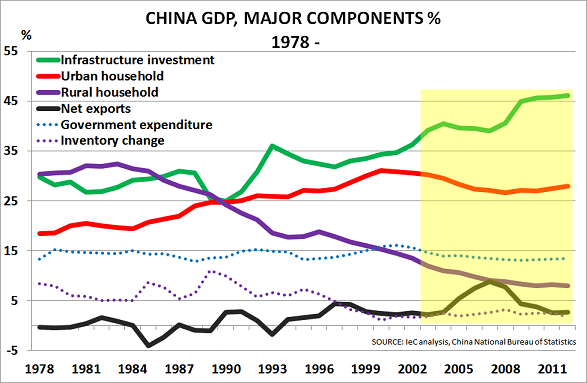

Public investment was made directly by central and local governments, and was also financed by the state-owned banks that lent huge amounts of money to mostly state-owned companies.

Later, these banks were also encouraged by the Chinese authorities to lend to mixed capital companies and even private groups, for the acceleration of domestic growth and international expansion.

These companies, public, mixed and private, have borrowed heavily to finance their growth. Public indebtedness has also increased significantly.

It is this bill that China is paying today.

High indebtedness, non-payment and high levels of default, in construction companies and beyond.

There has been no transition from the growth model to a private consumption base, which was essential

However, what happened was that there was no natural transition from the initial development model to a model more oriented towards private consumption.

On the one hand, there has continued to be an excessively insistence on public investment, which has low productivity and generates many inefficiencies.

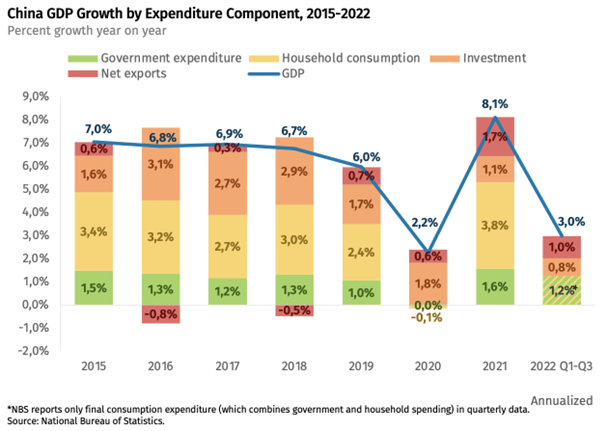

The big driver of growth has been public investment:

In a more recent period, consumption has been increasing its contribution to GDP growth:

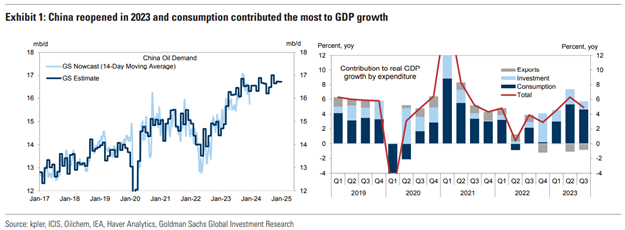

In 2022, consumption retracted due to the Covid shutdown and confinement, but has been recovering in recent times:

However, this recovery is far from what the authorities wanted.

In the following articles, we will continue to delve into each of these aspects and the consequences regarding the interest of the Chinese stock market for foreign investors.

This central question of the attractiveness of the Chinese market is very pertinent because, as we know, investing well means diversifying risks, doing so, above all, in the world’s largest economies and companies, and privileging those that are world leaders and consumer goods, in order to put the economy to work for us.