We are often bombarded with the reasons and predictions of stock market crises

There are always many times and many different reasons to sell and not be invested in the stock market

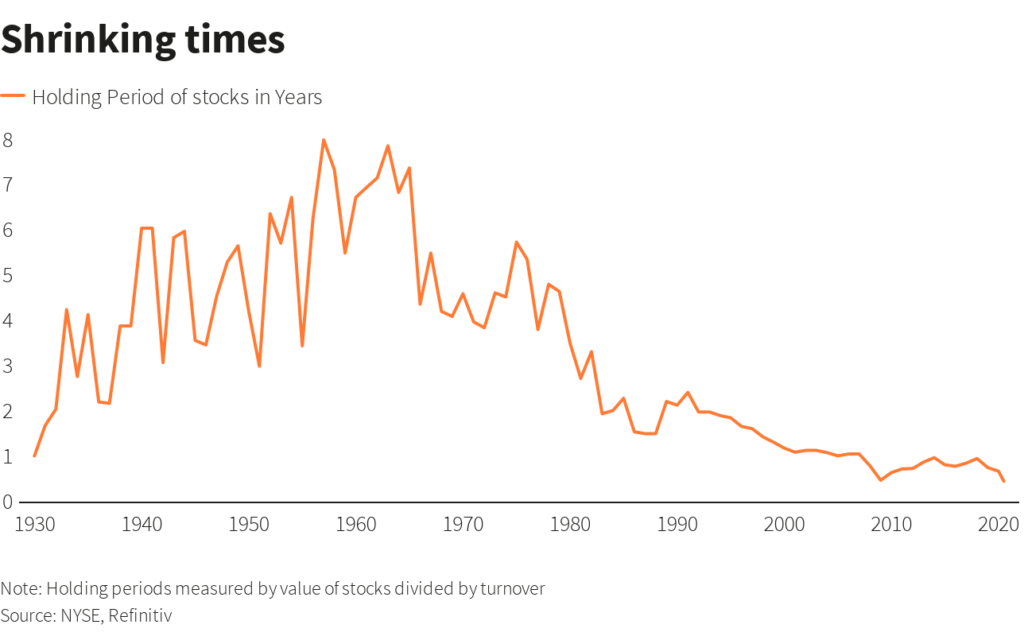

This instability translates into a reduction in the time it takes to invest in stocks, which has been decreasing since the 1960s and is at minimal levels

In a previous article we saw that it is difficult, if not impossible, to predict the evolution of stock markets in the short term and invest in their best moments.

This idea has a lot of costs and losses.

The conclusion we draw is that instead of trying to get the timing of the markets right, it is better to maximize the time invested in the markets.

In another article we saw that stock markets are volatile.

They have cycles, some shorter and others longer.

There are frequent technical fixes or even some crises.

But at the end of the day, they always revert to the average. Or better yet, they always recover from corrections and make new highs.

This conclusion reinforces the importance of maximizing the time invested.

Now, in this article, we will see how we are often tempted to change our course and make mistakes that cost us dearly.

In the second part, which we will publish in a parallel article, we analyze what we can do to combat these behavioral biases and how we should act in the face of market corrections.

We are often bombarded with the reasons and predictions of stock market crises

“The daily movements of the stock market are like a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, but signifying nothing.” – John Bogle, founder of Vanguard

In day-to-day news, even specialized ones, it seems that there are almost always good reasons to sell investments in the financial markets.

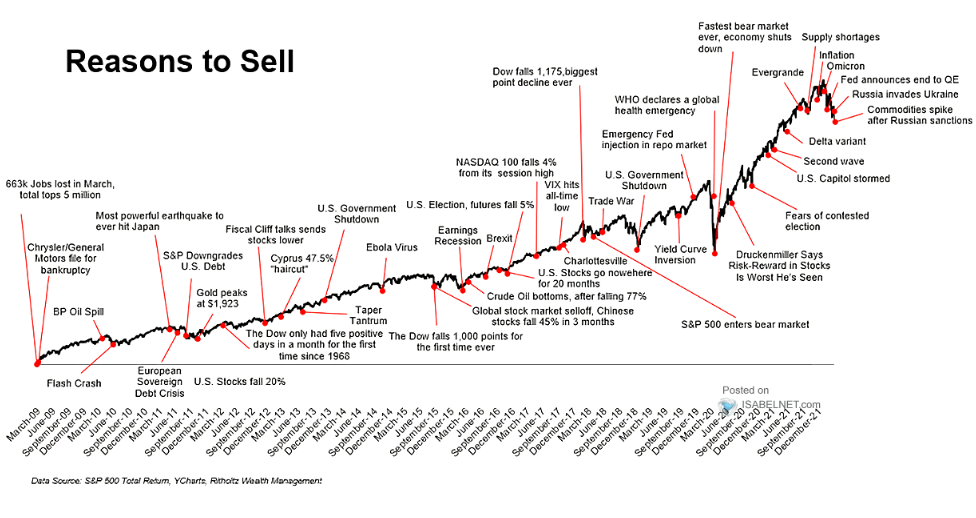

The following chart shows the example of some high-profile events that have occurred since March 2009 alone that some say justified this sale:

There are several dozen events, and for very different reasons.

From business bankruptcies, natural disasters, technical trading crashes, public debt crises, etc., a multitude of diverse economic, financial and political situations, and only in the largest developed countries.

Some of these predictions have gone down in history.

Mostly as flops, since they didn’t materialize.

There have been cases where they have materialized, but many years later.

However, the markets continued to rise and those who had sold would have lost those gains.

There were those who made the predictions right. Both in direction and time. However, these were very rare cases, truly exceptional.

For example, Nouriel Roubini (in 2005 and 2006), Michael Mayo (1999), Raghuram Rajan (2005-2006), Paul Singer (2006), Janet Yellen (early 2007), Warren Buffett (2006 and 2006), and John Paulson (2006) predicted the Great Financial Crisis of 2007.

However, these people are usually unable to repeat these feats.

In short, there are always good reasons to sell.

In fact, too many. And if we sold, in most cases we lost.

There are always many times and many different reasons to sell and not be invested in the stock market

Prophecies of crises, as well as their opposites, that is, of extraordinary gains, stimulate our behavioural biases and can lead us to great losses.

In an article we saw that these personal biases are our biggest enemy and we started to develop a series of articles that address some of the main biases.

In these we have presented some that are worth being constantly aware of, such as loss aversion, tailism or herd, current or recent memory, media noise, confirmation, mental calculation, familiarity, overconfidence, framing, anchoring, regret, etc.

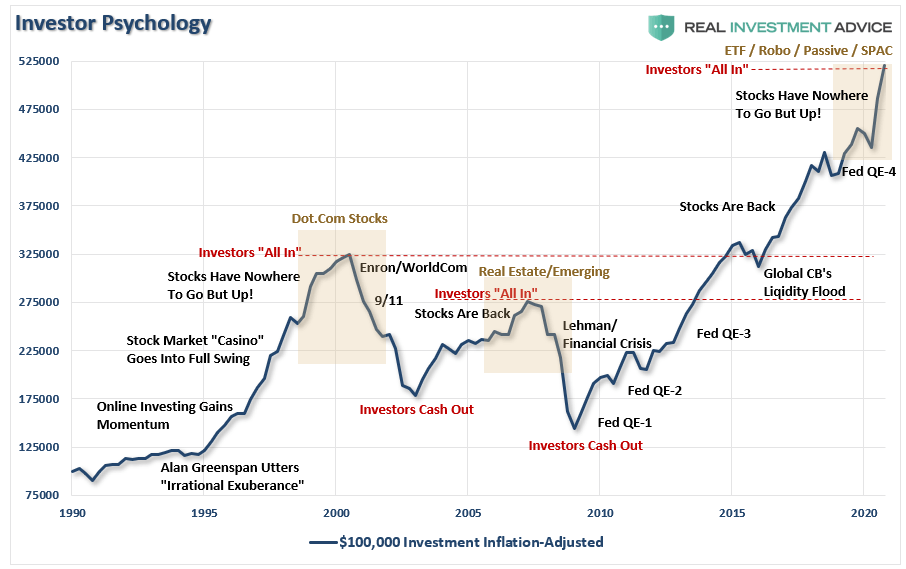

The following chart shows the evolution of the valuation of a $100,000 invested capital of the US stock market, in real terms, between 1990 and 2020:

In the first decade (1990-2000), there was a good appreciation, in the second (2000-2010) a loss and in the third (2010-2020) the gains were very strong.

The point is that usually investors chase and go after the market.

They invest all of what they have when the market is at highs and sell everything when it is at lows.

Thus, your investments in the market exceed the normal and appropriate allocation on the rise and fall far below that on the fall.

They move away from their proper allocation.

They get out of the middle ground and into excesses.

It feels like a real roller coaster, from euphoria to doom or capitulation.

Biases are normal. After all, we are human.

What should not be normal is the resulting reaction.

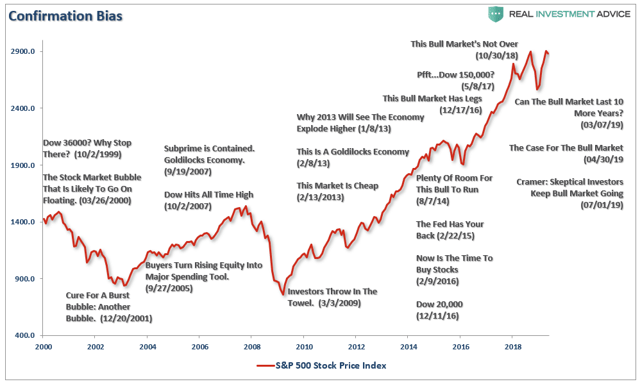

The following chart shows how our behaviors are influenced by the news, based on the evolution of the S&P 500 since 2000:

On February 10, 1999, after a decade of good gains, there were those who prophesied that the Dow Jones Industrial Average could go as high as 36,000.

Even today, more than 30 years later, it is still not there.

Then came the tech bubble and the market lost more than 50%.

On January 1, 2009, after two years of steep losses, investors threw in the towel and sold everything.

Minimums are reached.

Selling pressures are over and there are practically only purchases from institutional or professional investors.

Almost 4 years after the recovery, in February 2013, it is beginning to be said that the market is cheap.

In August of the same year, there were two opposing opinions, one that the economy was at a crossroads and the other that it would have explosive growth.

Between 2014 and 2016 the market went sideways and since then it has not stopped rising until the pandemic in 2020.

In 2019, there were those who admitted that the bull market could be another 10 years old.

This instability translates into a reduction in the time it takes to invest in stocks, which has been decreasing since the 1960s and is at minimal levels

The amplification of normal stock market fluctuations by the media causes investors to become unstable, and their behaviour to change.

One of the main manifestations is in the very time of holding investments.

In the following chart we see how the holding time of investments, measured by the quotient between the capitalization of shares and the traded volume, has evolved since 1930:

The period of detention went from 6 to 8 years between 1940 and 1980, to less than 1 year today.

We know that this information may exaggerate the true reality, since we are talking about the market as a whole, the action of all its agents, and not individual investors.

Even taking into account the fact that many institutional investors have a high turnover of their investments (and that, in the end, they manage funds from individual investors!) and that the drop in trading fees has made it easier for individual investors to increase volume, the truth is that the reduction is very substantial.

Therefore, the market in general and many individual investors are more speculators or “traders” than investors.

This situation is in stark contrast to the behavior of some of the best professional investors of all time, as we have seen in a previous article.