Bond prices, interest rates, inflation and credit rating

Treasury, or government, or sovereign bonds are seen as the benchmark for all others because they are usually the best credit risk and have the best rating in the country

Treasury bonds yields to maturity are also determined by inflation expectations

Usually, the longer the term the higher the bonds interest rate

The better the rating or credit risk the lower the level and interest rates and vice versa

Since bonds are loans made by holders to issuers, entitling to payments of the fixed coupon interest and the repayment of capital, they are thus subject to the risk of non-payment of the amounts due and the risk of increases in interest rates

Bonds are loans made by their holders to issuers. To that extent, they entitle them to payments of fixed coupon interest over the life of the loan and the repayment of capital normally at the end of the term.

In this way, bond investors are subject to the risk of non-payment on the amounts due, arising from financial difficulties that push issuers into default. If this happens the losses incurred will be given by the difference between the amount received and the amount of reimbursement due.

In addition, they are also subject to the risk of changes in interest rates. A general increase in interest rates means that all issuers must pay a higher rate for their loans, including those entitled to bonds. Bonds issued at lower interest rates will be worth less. In this case, the price drop or devaluation of bonds only becomes a loss if the bonds are sold by the investor before the capital reimbursement. On the contrary, there will be no loss of capital if the obligations are maintained until the date of repayment.

The price of bonds varies inversely with market interest rates and these are a function of the base or reference interest rate (usually that government bonds), expected inflation rate, term of issue and issuer credit risk

Bonds may be held until their capital reimbursement at the end of the term or maturity or sold before that time.

The return on the bond investment is given by the interest income received and the capital gains obtained between the acquisition value and the value of sale or repayment (if held to maturity) of the bonds.

The price or value of the bonds at each time is determined by the market interest rate and the probability of payment of the debt service by the issuer until the end of the term.

An increase in the market interest rate decreases the value of bonds, since new identical issues will be made at a higher rate and provide a better yield. A decrease in the issuer’s risk quality or credit rating also devalues bonds, as it increases the risk of default on the debt service (payment of interest or repayment of capital at the end).

Being more concrete, we have the following two conclusions:

- The bonds price or value varies inversely with changes in market interest rates;

- Market interest rates at each time are determined by the real risk-free or reference interest rate, expected inflation, the timing of the issue and the issuer’s credit risk or rating (where any).

The higher the expected inflation, obviously the higher the interest rate (loans are made in the expectation of obtaining a positive interest I real terms).

The longer the term, the higher the interest rate for two reasons: a) a longer term corresponds to greater expected inflation uncertainty; (b) the increase in time increases the likelihood of default by the debtor.

As we have seen the higher the credit risk (or as we shall see below, the worse the rating), the higher the bond interest rate, to pay investors for lending to debtors of lower risk quality.

At each time, the bonds price reflects the implied annual return on the investment in them if they are held until the final repayment, also known as yield to maturity.

Treasury, or government or sovereign bonds are seen as the benchmark for all others because they are usually the best credit risk and have the best rating in the country

Treasury bonds are typically regarded as the best rating level or lower credit risk in each country, given the financial capacity of governments to be able, if necessary, to raise taxes, to pay and comply with their debt service.

To that extent, the interest rates of the remaining bond issues are normally referred to the rate of Treasury bonds for the same period, plus a margin or spread of credit risk.

The Treasury bond current interest rate or yield to maturity is the sum of a short-term central bank rate plus the term spread

The treasury bonds issues in developed countries are made for the medium, long and very long terms, between 3 and more than 30 years, and the 10 years are market reference.

Interest rates issues and market yields are determined by the short-term and official interest rate of central banks, plus a margin or spread related to the issue’s term or maturity. This margin or term spread has two components:

- As inflation expectations, or an expected inflation rate;

- A credit risk spread for the deadline.

The credit risk spread plus the central bank rate correspond to the so-called real interest rate.

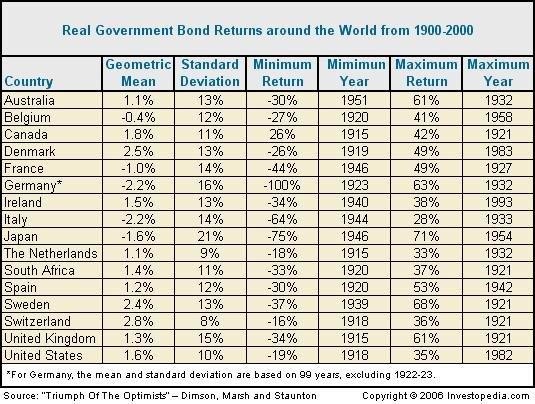

In the last century, the annual real yield of treasury bonds in developed countries has been very low and, in many cases, negative, being between -2.2% to 2.8% in the main geographies.

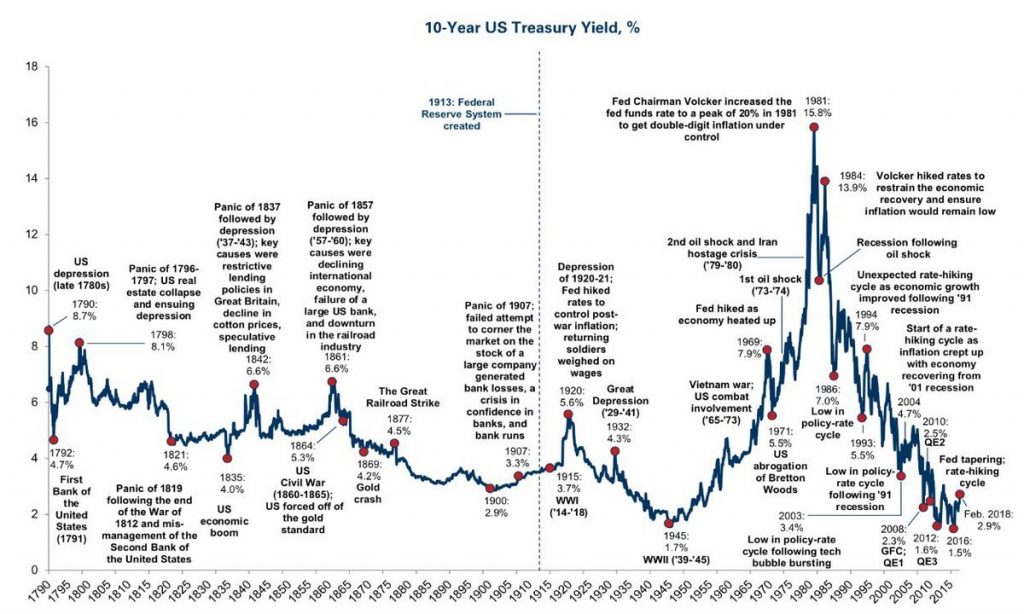

Over the past two centuries, the nominal interest rate on 10-year U.S. treasuries has been nearly 5 percent a year, reasonably stable at first and abnormally volatile in the most recent 60 years.

In recent years interest rates have been falling in the US and around the world, mainly due to the monetary policy adopted.

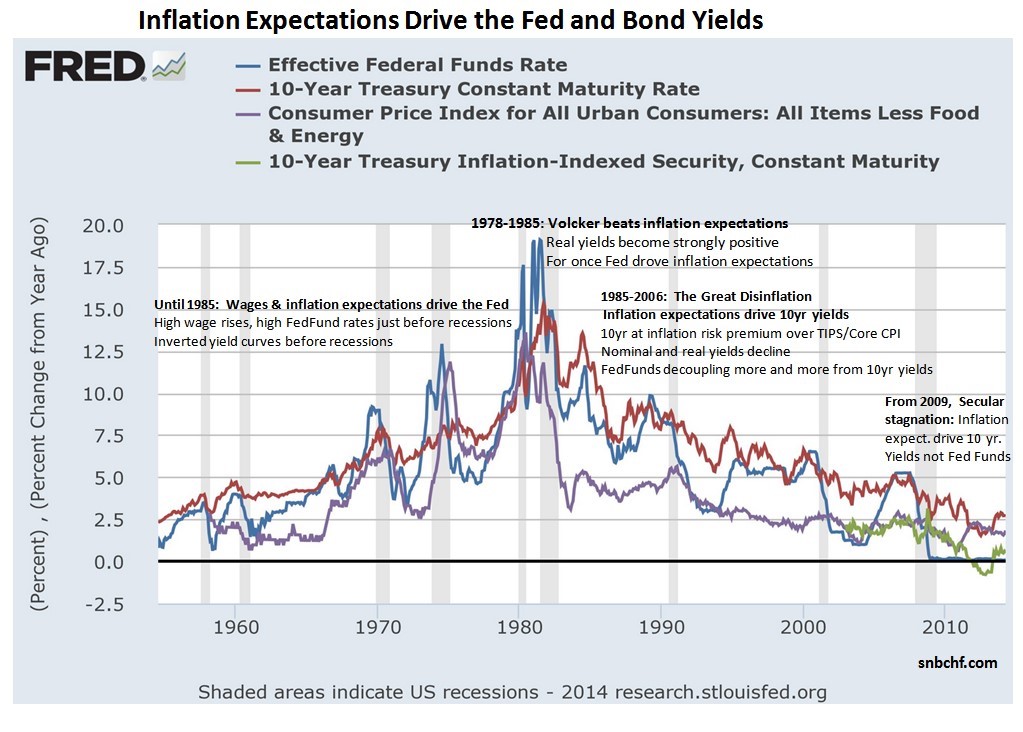

Treasury bonds yields to maturity are also determined by inflation expectations

The following graph shows the evolution of interest rates on 10-year treasury bonds, the FED central bank’s benchmark interest rate, inflation-indexed treasury bonds and the inflation rate:

We can see that one of the main determinants of the interest rate of treasury bonds (and central bank reference) at each moment are the inflation rate expectations.

Usually, the longer the term the higher the bonds interest rate

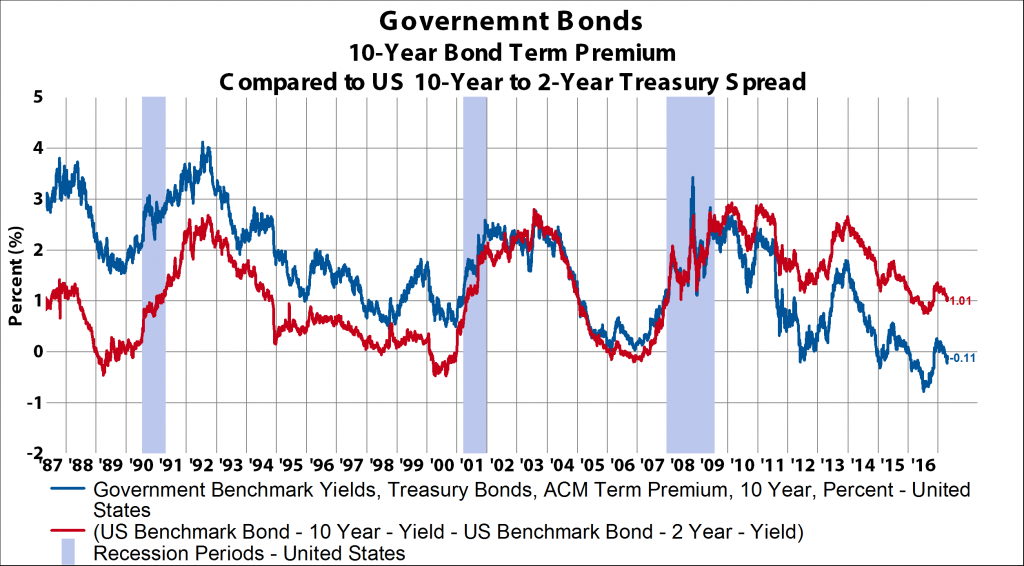

In the following chart we can see the evolution of interest rates on 2- and 10-year treasury bonds, as well as their margin or spread:

The interest rate difference for 2-year to 10-year treasury bonds is about 1% p.a., on average.

This difference is usually positive, but it is not always so. Exceptions arise in periods when a deflationary or economic contraction is coming.

The assessment and classification of credit risk and bond rating and their relationship to the issuer’s probabilities of default

The interest rate or the market yield prevailing on the bond of each issuer is determined by the interest rate of treasury bonds plus the issue credit risk spread.

Credit risk is measured by the issuer rating or ability to pay the debt service and the characteristics of the issue (in terms of graduation on the scale of creditors or associated collateral). It is a measure that seeks to summarise the quality of the debt, measured in terms of the ability of the issuer to reimburse its capital.

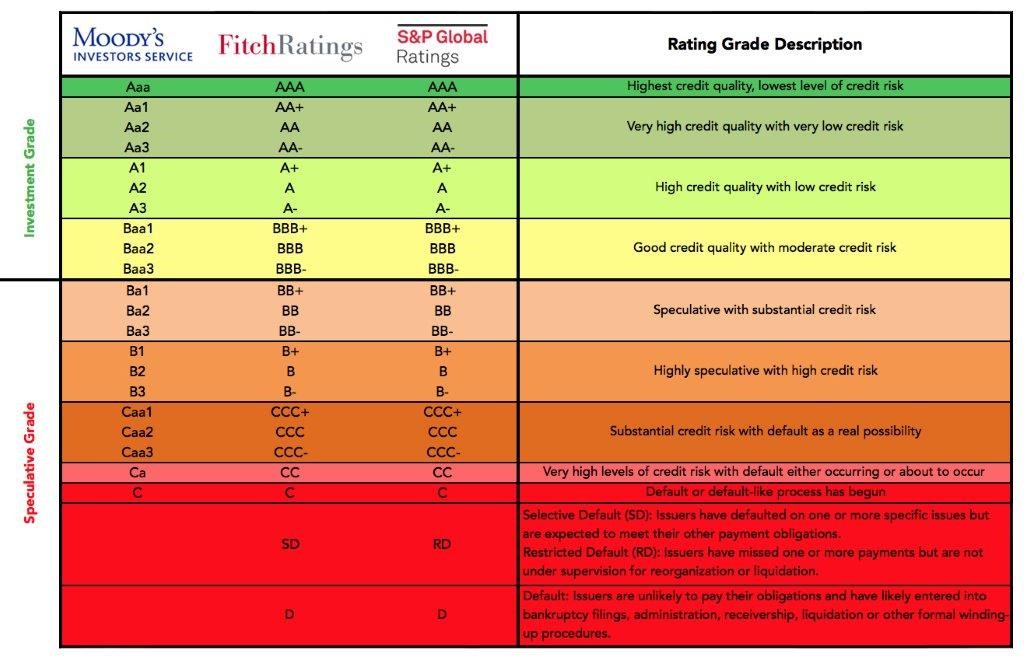

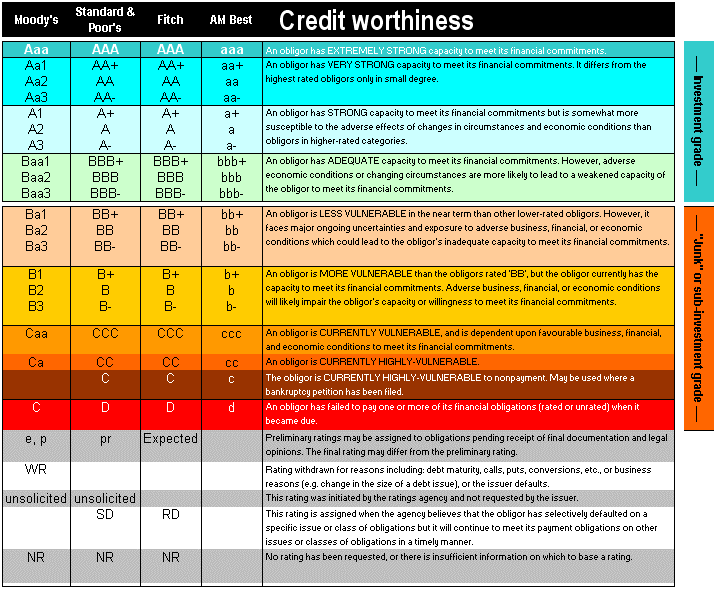

The three main rating agencies – Moody’s, Fitch and S&P – rank the rating of issues on a scale ranging from AAA to D. Ratings equal to or greater than BBB are of investment grade or quality and ratings equal to BB or less are called speculative grade or junk.

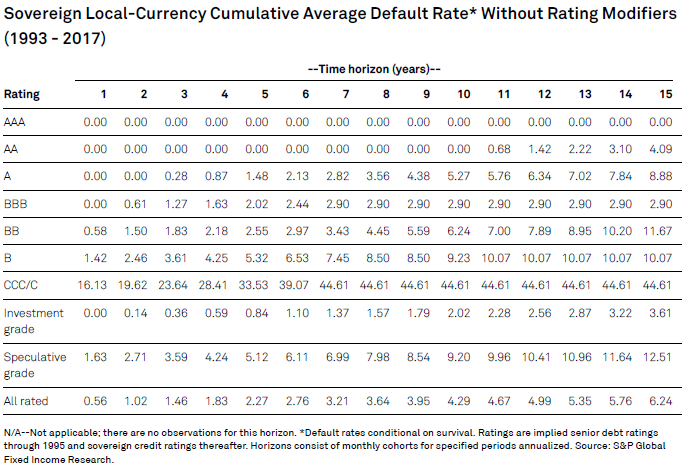

The following table shows the probabilities of default of various rating levels for government and business issuers in the U.S. for the period 1993-2017:

We clearly see that the worse the rating, the higher the probability of default. We can also verify that the default increases with time.

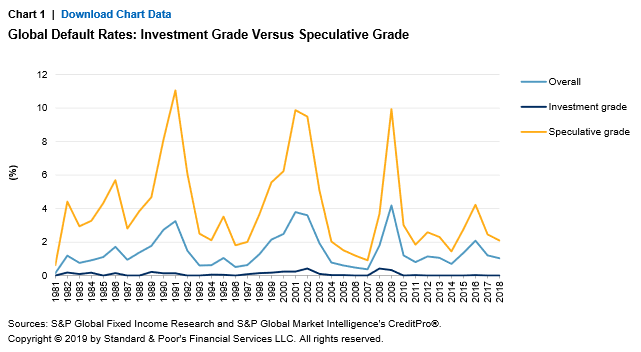

The following graph shows the evolution of default rates of bonds of investment and speculative grades between 1981 and 2018:

It is the graphic image of the previous relationship between rating and default rates. We see that the percentage of default is not only higher but is also much more volatile and especially more extreme in speculative grade than investment grade rating.

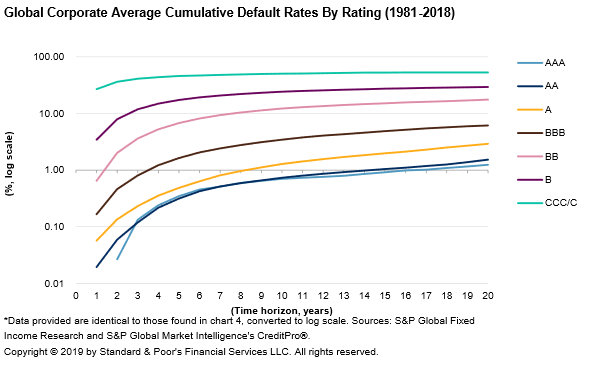

The following graph contains the time evolution of the probability of default:

Again, it is the graphic image of the relationship between rating and time. The probability of default with the BBB rating which is the lowest degree of investment grade is less than 1% up to 3 years but increases to about 3% for periods of 10 to 15 years. In the case of the BB rating, the highest of speculative grade, the probability of default goes from less than 1% to 1 year to more than 5% to 10 years and from 10% to 15 years.

The better the rating or credit risk the lower the level and interest rates and vice versa

As expected, the better the rating the lower the bond interest rate or yields. The interest rate must be higher to offset the greater risk of capital loss.

The market’s benchmark interest rate is that of treasury bonds. At this rate a spread is added to translate the credit risk margin.

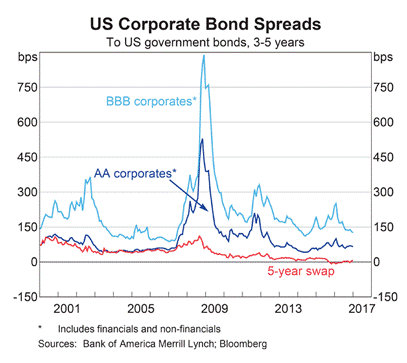

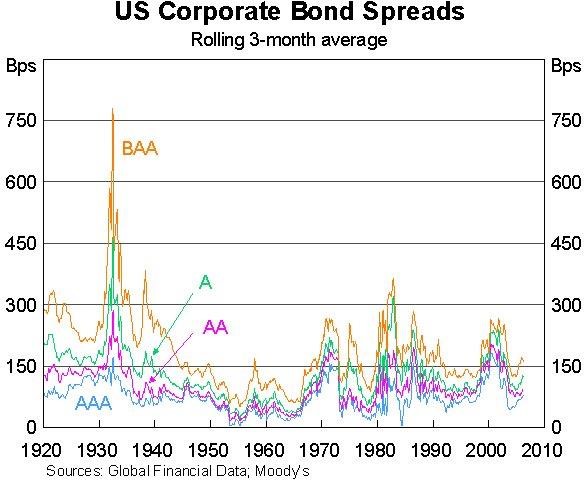

The following charts show the evolution of credit spreads of US companies’ bond issues:

Historically, the difference or spread between investment and speculative rating bonds has been 3% to 4%. This difference is naturally aggravated in periods of stress in financial markets, such as the Great Depression, oil crises, the technology bubble and, also as we will see in the following chart, during the Great Financial Crisis: