China has been slowing down in recent years and the expectation of a resumption of economic activity in the post-Covid period has been disappointed

Long-term economic growth prospects are lower

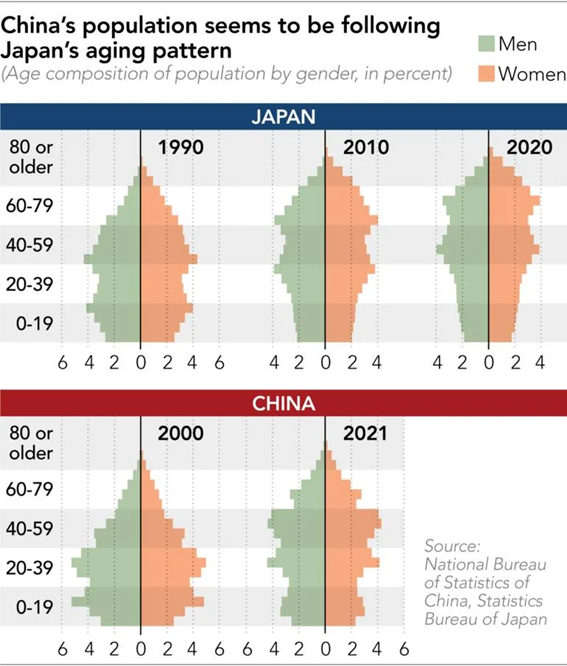

China faces a major problem with an ageing population

The demographic similarities between present-day China and Japan’s lost decades of the 1990s bring to mind the threat of Japan-like stagnation

This article is part of a series dedicated to investing in Chinese stocks.

In the first article, a general introduction to the topic was made,including a synthesis of the remarkable performance of economic growth and development in the last 4 decades, as well as the challenges it has faced especially since mid-2015.

In the second article, aspects of China’s strong economic growth over the past 4 decades were developed.

The third article was divided into two parts, the first addressing the performance of the Chinese stock market in the last 4 decades, while the second provided a framework for the prospects of foreign investors’ understanding of the economic reality and the markets.

In the fourth article, also divided into two parts, we began to develop the main challenges of the Chinese economy.

In this article we analysed how it all started, the problem of the construction sector, explaining its direct and also indirect effects.

It was thought that this would be the central problem, combined with the draconian Covid response policy.

But appearances are often deceiving.

In previous articles we have shown that China’s problem is deeper and more structural, and focuses on the lack of change in the economic development model, from an economy based on public investment to an economy driven by private consumption.

Chinese government authorities intend to stimulate and boost consumption to grow the economy, but have been unable to achieve this goal.

In the last article we tried to explain this, starting with the prudent response of households to recent insecurity in terms of growth, wealth, income and employment.

In this article, we continue with the explanation, focusing on the problem of demography.

In previous articles we have already developed the size and weight of the Chinese economy in global terms, its enrichment in recent years, as well as its convergence with the most developed countries.

Also in previous articles we have addressed the growth of investment in emerging equity markets, as well as their attractiveness, with emphasis on the Chinese market.

In another article, we also delved into the specifics of the structure, functioning and activity of the Chinese stock market.

China has been slowing down in recent years and the expectation of a resumption of economic activity in the post-Covid period has been disappointed

China’s economic growth rates have been declining.

After a strong start to 2023 following the 2022 shutdown due to overly restrictive Covid containment policies, Chinese economic activity has fallen far short of expectations.

Exports collapsed. Consumption, production and investment have slowed, while inflation has stabilised and the unemployment rate has risen.

The Chinese renminbi hit new lows in August and September 2023, driven by concerns about the domestic economy.

The Chinese economic miracle seems to be over, not least because no miracle lasts forever.

The higher incomes and higher labour costs they create, deteriorating external conditions and an ageing population are serious long-term headwinds against high growth.

Long-term economic growth prospects are lower

The IMF has also become more pessimistic about the long-term outlook.

In November, it expected China’s growth rate to reach 5.4% in 2023 and gradually slow to 3.5% in 2028, amid headwinds ranging from weak productivity to an aging population.

Despite its many problems — a housing crisis, weak spending and high youth unemployment — most economists believe the world’s second-largest economy will hit its official growth target of around 5% in 2024.

But without major market reforms, the country could get stuck in what economists call the “middle-income trap.”

This refers to the widespread notion that emerging economies quickly rise out of poverty only to be trapped before they reach high-income status.

China faces a major problem with an ageing population

Demographics are a persistent, long-term obstacle.

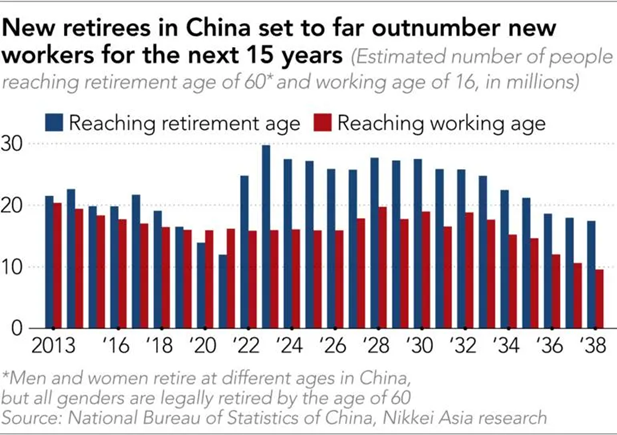

China’s working-age population has been declining for several years, with fewer young people entering the labour market and more people retiring:

The effect of demographic ageing on China’s economy will be structural, as it has been in other Asian countries.

Japan and South Korea are among the fastest aging countries in the world, with South Korea having the lowest fertility rate in the world.

Singapore, Thailand and Taiwan are also declining in population, while population growth is slowing in Vietnam, the Philippines and elsewhere.

In the more fortunate countries, aging happens when the country is already relatively prosperous, which means that many of its seniors can enjoy a comfortable retirement.

Japan, for example, saw its average income reach the levels of developed countries well before its population began to stabilise, a peak that corresponded with the end of its economic bubble in the late 1980s.

Not yet a high-income country, its shrinking population may be an obstacle to economic growth, as a massive population of pensioners will claim an ever-increasing share of the available resources.

As their workforce shrinks, so does the burden on pensions and the health system.

The demographic similarities between present-day China and Japan’s lost decades of the 1990s bring to mind the threat of Japan-like stagnation

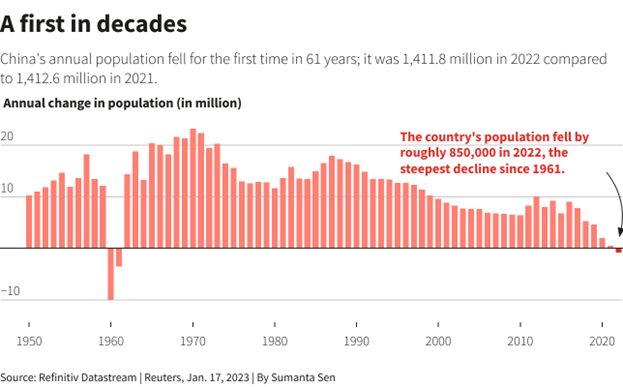

The falling birth rate in China is a major concern.

China’s fertility rate fell below 1.1 in 2022, and as we know, it takes a rate of 2.1 to sustain a population.

In 2021, official statistics indicated a population growth of only 480,000 people (+0.03%), which means that China’s demographic peak has arrived.

In addition, there are serious concerns about the educational preparation of tens of millions of rural Chinese youth for entry into a 21st-century economy.

In 2022, for the first time, there was a population regression in China, with the loss of 850 thousand people:

China’s population decline will have major effects on its economic system.

In Japan, for example, the issue has led to labor shortages, lower consumption, shrinking industry, larger fiscal deficits, and lower interest rates.

Several experts point to a 15- to 20-year lag between Japan and China in terms of demographic maturation.

The working-age population began to decline in 2015 in China versus in 1995 in Japan, while population decline began in 2022 in China versus 2008 in Japan:

China is also experiencing greater fiscal pressure, with its debt expected to rise to 155% of GDP in five years, according to the IMF in 2022.

In the following articles, we will continue to delve into each of these aspects and the consequences regarding the interest of the Chinese stock market for foreign investors.

This central question of the attractiveness of the Chinese market is very pertinent because, as we know, investing well means diversifying risks, doing so, above all, in the world’s largest economies and companies, and privileging those that are world leaders and consumer goods, in order to put the economy to work for us.