In the last 3 years, Chinese stocks have lost $3 trillion and 60% of their value, due to risk aversion associated with economic and geopolitical factors

And the declines continue at the beginning of this year

China is clearly underperforming compared to other Asian countries

This underperformance of the Chinese stock market is even more significant when compared to the American market, resulting in the opening of a capitalization gap of 38 billion dollars and a valuation almost 60% cheaper in the last 3 years

Chinese stocks have never been cheaper! To the point that some have raised the question of whether the Chinese stock market is investable or not

This article is part of a series dedicated to investing in Chinese stocks.

In the second article, aspects of China’s strong economic growth over the past 4 decades were developed.

The third article was divided into two parts, in the first addressing the performance of the Chinese stock market in the last 4 decades, while in the second, a framework was made of the perspectives of the current understanding of the economic reality and the markets by foreign investors.

In the fourth article, also divided into two parts, we began to develop the main challenges of the Chinese economy.

In this article we analysed how it all started, the problem of the construction sector, explaining its direct and also indirect effects.

It was thought that this would be the central problem, combined with the draconian Covid response policy.

But appearances are often deceiving.

In the most recent articles we have shown that China’s problem is deeper and more structural, and focuses on the lack of change in the economic development model, from an economy based on public investment to an economy driven by private consumption.

Chinese government authorities intend to stimulate and boost consumption to grow the economy, but have been unable to achieve this goal.

We have already touched on two of the reasons, the response of households to financial insecurity and the problem of demography.

In the last article we continued to give an explanation for this fact, now focusing on the themes of the political, economic and social model, as well as on geopolitical problems.

In previous articles we have already developed the size and weight of the Chinese economy in global terms, its enrichment in recent years, as well as its convergence with the most developed countries.

Also in previous articles we have addressed the growth of investment in emerging equity markets, as well as their attractiveness, with emphasis on the Chinese market.

In another article, we also delved into the specifics of the structure, functioning and activity of the Chinese stock market.

In this article we develop in more detail the fall of Chinese stocks in the last 3 years and argue that it is not only economic and financial reasons that we have seen earlier that have caused this fall.

There are other reasons that have to do with the development of the capital market itself, and above all with the direction that the Chinese authorities want to give it.

The exit of foreign investors from the Chinese capital market was also due to a disappointment with the authorities’ interventions in the market, which led many to wonder if the Chinese market is investable.

This factor is also a key element for the fall in the value of shares and will be decisive for future developments.

In the last 3 years, Chinese stocks have lost $3 trillion and 60% of their value due to risk aversion associated with economic and geopolitical factors

This aversion to China’s stocks among global investors has become more entrenched over the past 12 months thanks to weak economic growth, an unresolved crisis in the property sector, insufficient government support for markets, and frayed diplomatic relations between Beijing and Washington.

In addition to economic and geopolitical concerns, some of China’s trade practices are also keeping foreign investors out of the market.

In particular, the Beijing authorities’ regulatory crackdown on China’s tech sector is weighing on foreign investor sentiment towards the country.

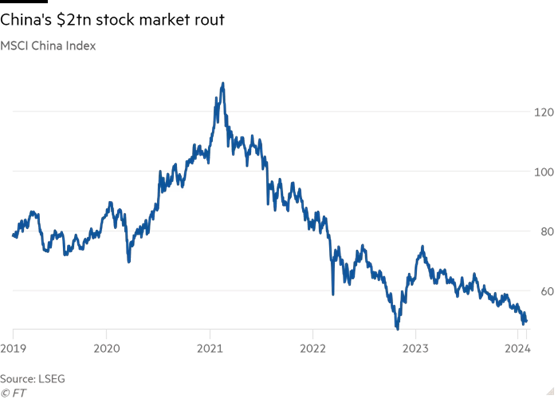

As a result, the benchmark MSCI China stock index is down more than 60% from its early 2021 peak, reflecting a loss of more than $1.9 trillion from market capitalization during that period:

Chinese stock market indices are at their lowest level since 2019:

And the declines continued earlier this year

The benchmark CSI 300 index for domestically traded stocks has fallen more than 5% this year after taking into account the renminbi’s depreciation against the dollar.

Foreign investors have been selling a large number of shares of Chinese companies, sending down share prices, especially those listed in New York and Hong Kong.

Foreign investors sold about 90% of the $33 billion in Chinese stocks they had bought earlier this year by the end of 2023 and have continued to sell this year.

International institutional investors have also been net sellers of approximately 1 trillion yuan ($148 billion) of Chinese bonds since the beginning of 2022.

The outflows sharpened after Beijing confirmed that China’s annual growth was the slowest in decades and revealed that the country’s population decline had accelerated in 2023.

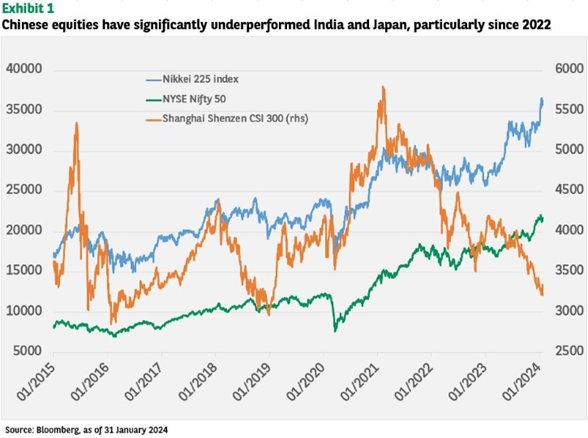

China is clearly underperforming compared to other Asian countries

China’s stock market has been one of the worst performers in the world, with the Shanghai Shenzhen CSI 300 down around 20% from August 2023 to the end of that year.

This decline is partly due to the steady deterioration in China’s growth expectations, aggravated by weak macroeconomic and fiscal stimulus.

In recent weeks, Chinese authorities have announced measures to bolster stock markets.

This follows a dismal start to the year for Chinese equities, with Tokyo overtaking Shanghai as Asia’s largest stock market, while India’s valuation premium over China hit a record high.

This underperformance of the Chinese stock market is even more significant when compared to the US market, resulting in the opening of a capitalization gap of 38 billion dollars and a valuation of 60% cheaper, in the last 3 years

Over the past 3 years, strong sell-offs in Chinese equities have resulted in a record $38 billion gap with U.S. equities.

And the MSCI China index is 60% cheaper than the U.S. stock market benchmark:

Chinese stocks have never been cheaper! To the point that some have raised the question of whether the Chinese stock market is investable or not

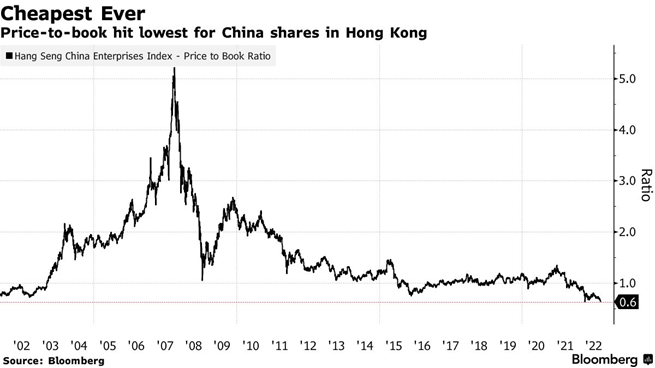

Chinese stocks listed in Hong Kong are trading at prices that correspond to the lowest valuation ever recorded, taking as a reference the multiples of price to book value:

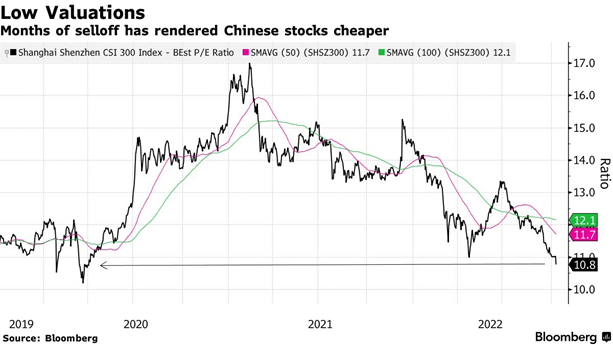

In terms of price-earnings multiples (PER), the current valuations of the CSI 300 index of the Shanghai Shenzen stock exchanges are at their lowest level since April 2010, in the aftermath of the start of the pandemic:

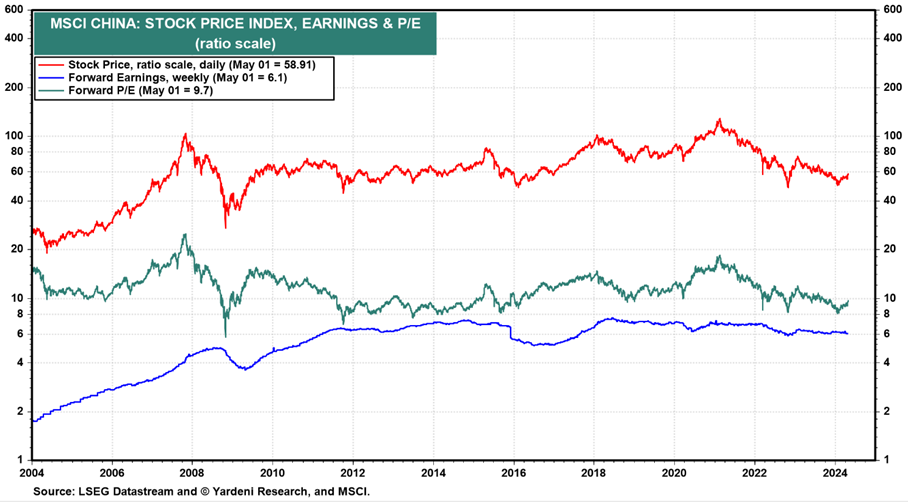

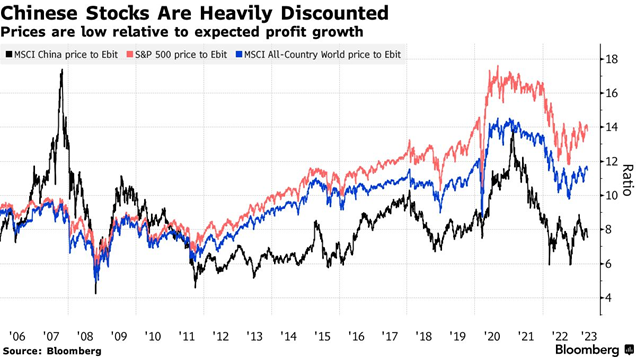

Over a longer horizon, the price valuation multiples relative to operating income of the MSCI China index are at very depressed levels in historical terms (only comparable to the period between 2011 and 2015):

In relative terms, the situation is also impressive.

The 8x multiples are half of U.S. levels and one-third lower than world levels.

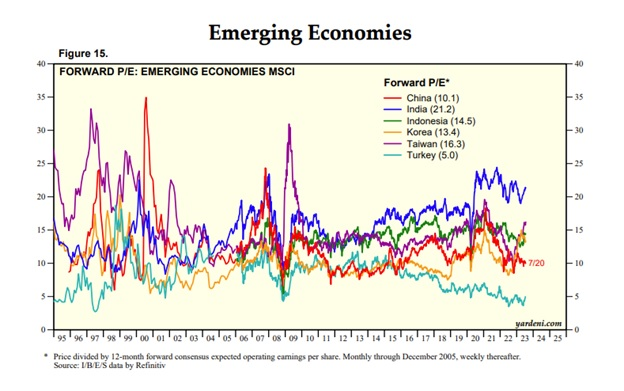

China is trading at a forward price-earnings multiple of about 10.1x, half that of the U.S. at 20.2.

That’s the biggest difference in valuation between the two countries in 20 years.

Given that China and the U.S. are the world’s two largest economies, one might wonder why the difference in valuation between the two nations is so great.

Many investors have been selling heavily in China’s stocks over the past couple of years, often in favor of other markets such as India.

For example, MSCI data shows that India is trading at a forward price-earnings multiple of 21.2x, more in line with the U.S. value, despite the disparities between the two countries.

Japan is trading at a PER multiple of 14.4x, and emerging markets as a whole are trading at a forward P/E of 12.3x.

This central question of the attractiveness of the Chinese market is very pertinent because, as we know, investing well means diversifying risks, doing so, above all, in the world’s largest economies and companies, and privileging those that are world leaders and consumer goods, in order to put the economy to work for us.